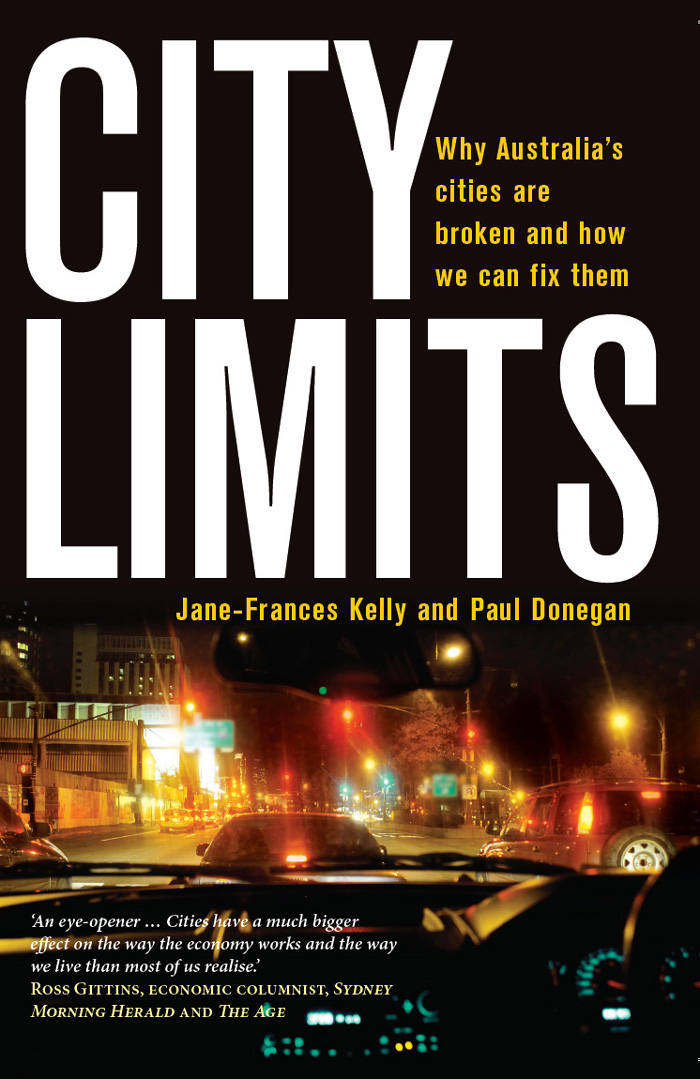

Jane-Frances Kelly was Cities Program Director at the Grattan Institute from 2009 to 2014. She has led strategy work for the United Kingdom, Queensland, Victorian and Commonwealth governments. Prior to moving to Australia in 2004, she spent three years in the British Prime Ministers Strategy Unit.

Paul Donegan is Fellow, Cities at the Grattan Institute. He has helped governments tackle some of Australias biggest social and economic challenges, as a Commonwealth and state public servant, ministerial adviser and at the Grattan Institute.

MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY PRESS

An imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Limited

1115 Argyle Place South, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

mup-info@unimelb.edu.au

www.mup.com.au

First published 2015

Text Grattan Institute, 2015

Design and typography Melbourne University Publishing Limited, 2015

This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publishers.

Every attempt has been made to locate the copyright holders for material quoted in this book. Any person or organisation that may have been overlooked or misattributed may contact the publisher.

Cover design by Nada Backovic

Typeset by Typeskill

Printed in Australia by McPhersons Printing Group

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Kelly, Jane-Frances, author.

City limits: why Australias cities are broken and how we

can fix them/Jane-Frances Kelly and

Paul Donegan.

9780522868005 (paperback)

9780522868012 (ebook)

Includes index.

UrbanizationAustralia.

Sociology, UrbanAustralia.

City planningAustralia.

Cities and townsAustraliaGrowth.

Community development, UrbanAustralia.

Donegan, Paul, author.

307.760994

CONTENTS

Introduction

Australia is a nation of city-dwellers. Many of the joys of Australian lifeits energy, optimism, cultural diversity, good food, green space and passion for sport and the outdoorsare found in cities. Many of its problems are as well.

Home ownership among younger people is declining, while renters, who make up one in four households, face insecurity and instability. As more people live further from city centres, traffic congestion is getting worse. For many, commuting is becoming intolerable. Social isolation is deepening, while polarisation between rich and poor, young and old, the inner city and suburbs, continues to grow. Failure to manage our cities well is hurting our economy.

This is a book about these problems, and how to solve them. Over the next eight chapters, we will explore what life is like today in Australias cities. We will meet individuals, couples and families all struggling with situations our cities have imposed on them. In a few cases names have been changed at a persons request, but all case studies are of real people in real situations.

Across the world, leaders, policymakers and experts are paying increasing attention to cities and the benefits they bring. Developing countries know that rapid urbanisation is good for the living standards of their population. Australians are lucky that so many of us already live in cities. But we barely recognise our luck, and were in danger of wasting it.

Partly this happens because were complacent about our cities. They arent central to our national identity. Australian cities rank highly on international liveability league tables, giving us an excuse to ignore their problems. But many Australians lived experience of cities is quite different from what international rankings designed for globetrotting executives suggest.

asks why we live in cities, and looks at their evolving role in Australian history. It looks at how cities work, the trade-offs and hard decisions they confront us with, and what we need from them.

looks at how we depend on cities for jobs and good living standards in the evolving global economy. We see how the greatest concentrations of economic activity in Australia are not in the Pilbara and other mining regions, but in the centres of our largest cities. To be productive, businesses need a choice of potential employees, while employees likewise benefit from as wide a choice of potential employers as possible. The chapter asks whether Australian cities do a good job of connecting people and jobsa critical task in an economy where we increasingly rely on our brains to earn a living.

looks at how cities affect the opportunities available to usthe fair go. Being able to get to a good choice of jobs in a reasonable commute time is vital to individuals. If people have no choice but to live far from jobs and transport, they will have fewer jobs they can get to, making it harder to build their skills, and making them more vulnerable if they lose their job. Difficult and expensive commutes can also take a considerable toll on family life, leaving many women in particular to face very hard choices.

Of course, we are not just workers and employees. looks at social connection, perhaps our most important psychological need, and how our cities can help or hinder it. At a time when single-person and single-parent households are growing fast, we look at how limited housing choices and inadequate transport leave many at risk of isolation and loneliness.

options, but the market isnt supplying them. Australia confronts an increasing divide between older home owners and a younger generation that is either locked out of home ownership or pushed to the fringes of cities, far from jobs and good transport.

looks at how we get around our cities. More and more Australians face longer commutes over longer distances. Roads are congested, while public transport is not a realistic alternative to driving on congested roads in many areas, especially outside the inner city.

looks at why we are not only failing to fix these urgent problems, but are barely recognising them. Cities are caught between the three tiers of Australian government, hardly registering on the agenda of many politicians. Yet their leadership is also poor because many residents are unwilling to consider the possibility that cities could get better. And so we get short-termism and failure: easy answers that dont work, plans that never happen, and more of the same things weve been doing, even when these make matters worse.

Yet there are reasons to be hopeful. Cities have been turned around before. Some overseas cities are models of change and decision-making that have involved all residents in shaping the future. The final chapter outlines the kinds of changes that would fix our cities, and build a richer, fairer, better Australia. The ideas exist. We only need the courage to adopt them.

Chapter 1

A nation of cities

IN AUSTRALIA WE BELIEVE many myths about our country. We think we are laid-back, but we work some of the longest hours in the world. In the spirit of Ned Kelly, we think of ourselves as anti-authoritarian, yet we comply with seatbelt and bicycle helmet regulations, and nearly all of us vote in elections, as the law requires.

When we Australians portrayed ourselves to the world in the opening ceremony of the 2000 Sydney Olympics, we chose 120 stockmen and women dressed in bush clothing and riding horses to the movie soundtrack of