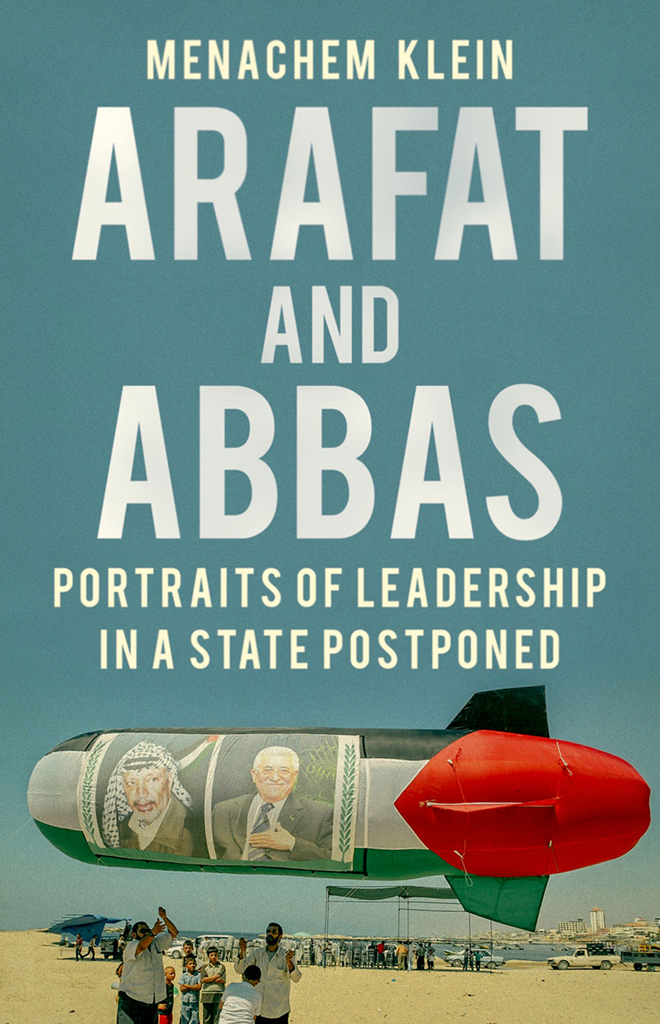

ARAFAT AND ABBAS

MENACHEM KLEIN

Arafat and Abbas

Portraits of Leadership in a

State Postponed

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Menachem Klein, 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

ISBN 9780190087586 (print)

ISBN 9780197513811 (updf)

ISBN 9780197513880 (epub)

Names: Menachem Klein

Title: Arafat and Abbas

CONTENTS

On a hot August day in 1993, I was in my Jerusalem home, unpacking my luggage after a fellowship year at St. Antonys College, Oxford, when the phone rang. On the other end of the line was the Voice of Israel correspondent for Palestinian affairs. He wanted to interview me on the breaking news: Israel and the PLO had agreed on mutual recognition through the Oslo Accords. As a junior researcher at the Hebrew University, I had followed Palestinian affairs since 1990. However, my main field of study was Egypts society and culture, on which I submitted my PhD in 1992. When I heard the news, I sharply switched my academic focus. I was later to become involved in formal and unofficial IsraeliPalestinian peace talks. The portraits of Arafat and Abbas this book offers, based on twenty-five years of following their lives closely, are the outcome of that phone call.

Like many others in the region and beyond, in 1993 I considered the Oslo agreement to be the precursor to a forthcoming peace treaty. It turned out to be much less, merely an interim agreement on establishing Palestinian autonomy, postponing for seven years the decision on its final status. I did not know that both Rabin and Peres opposed any solution that involved an independent Palestine.fall of the Berlin Wall, the liberation of Eastern Europe, the expansion of the European Union and globalisation. Twenty-five years later, it is clear that I was wrong to assume that the Oslo process was unstoppable or irreversible. IsraeliPalestinian peace, bringing this interim stage to an end, does not seem to be on the horizon. An ethnocentricreligious government rules Israel, and the Palestinian Authority is far from democratic. International media reports regularly on IsraeliPalestinian clashes, between stories on natural disasters. The young twenty-first century resembles the first decades of the twentieth century, rather than its end. Populist and authoritarian regimes have been elected in central Europe, American President Donald Trump is isolating the US from its western European allies and the European Union faces cracks in its foundations, not least with Brexit. The glory of the twentieth centurys anti-colonial struggles is over. Along with the playing upon fear of jihadist terror, populists have warned that immigration from the Middle East and Africa will lead to western Europe societies losing their national identity and social cohesion. Wracked by civil wars and unrest, the Middle East seems in a hopeless situation.

However, as this book suggests, a close examination of Palestinian social dynamics shows that beneath the present state of affairs, the potential for change lurks. An occupation that today seems permanent could be pushed away tomorrow by a nation determined to achieve liberation and self-determination.

This book is a portrait of two political leaders, each at the head of a twenty-five year old political entity. The components of each portrait do not fit together perfectly, nor depict a photo-realistic view of the subject. In addition, as with any portrait, the depictions of Arafat and Abbas include my interpretation of the facts of history. The first chapter describes the two personalities and their roads to power. The second concerns their foreign policy, in particular the relations with Israel and the US. In the third chapter, I deal with domestic policy, with special attention to democratic institution-building and state logistics. This chapter also deals with Hamas, the political rival that grew to challenge Arafat and Abbas. The final chapter describes the struggle to succeed Abbas, already underway. Through the book, I compare the two leaders. The dual portrait of these two presidents is more than a description of iconic individuals. It is a political profile of the whole Oslo Agreements generation.

The Iconic Personality

Yasser Arafat, the first president of the Palestinian Authority (PA), left behind big shoes to fill. This was not because Arafat built well-functioning state-like institutionsquite the contrary. They were big due to what Arafat had already symbolised before his election as PA president in 1996, along with the mysterious illness and circumstances surrounding his death in 2004.

Already at an early stage of his public life, Yasser Arafat became an icon. This was a reason he survived politically, despite his personal limitations. It started with the Battle of Karameh, in March 1968, in which Israeli forces suffered heavy casualties in the first major engagement since their glorious victory in the Six Day War eight months earlier. The Jordanian army caused most of the Israeli Defence Force (IDF)s lossestwenty-eight dead and ninety woundedbut Fatah benefited most by shrewdly claiming responsibility for the Israeli casualties. Styled as Fatahs leader and spokesperson, Arafat was interviewed and photo He was not necessarily the most talented of the Palestinian activists at the end of the 1960s, nor a natural leader. His colleagues all knew his deficiencies, which Arafat did not try to hide. Nor did he gain leadership of Fatah due to his family ties with the Grand Mufti Haj Amin al-Husseini, the leader of the national movement during the first half of the twentieth century. In fact, Arafat omitted al-Husseini from his family name. After the defeat of 1948, identifying with the failed Palestinian leader was a political burden, not a shortcut to the top.

But following a frequently trodden path within revolutionary groups, he was the only one among his Fatah comrades in the late 1950s and early 60s who agreed to devote all of his time to the new organisation. Unlike him, Arafats colleagues were refugees obliged to support their families and secure their future by developing professional careers. Founded in 1959 in Kuwait, Fatah rejected Egyptian President Nassers strategy for liberating Palestine through a well-prepared concerted attack by the surrounding Arab states. Instead of placing their trust in their neighbours, Fatah called on the Palestinians to rely upon themselves and launch a guerrilla war against Israel. Fatah was at that time a small organisation, founded by a dozen young activists, and until 1968 it had only about 500 members. The Palestinian public supported Nasser, and most of them had never heard of Fatah, let alone its counter-strategy. The young refugees who established Fatah looked elsewhere to secure their and their families futures. Arafat, who was not a refugee, opted differently.