CONTENTS

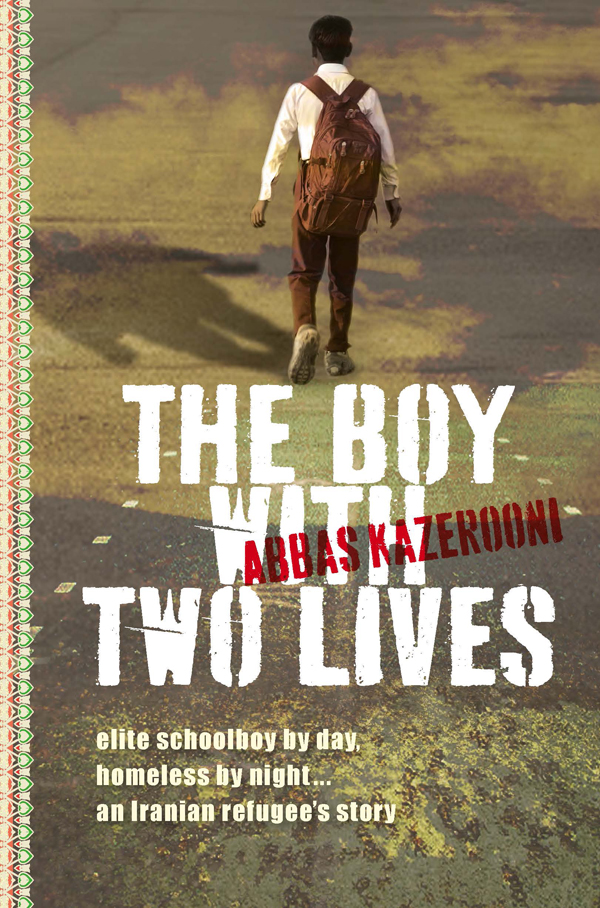

I was woken from a deep sleep by the echoing clang of the morning bell, followed almost at once by the thud of childrens feet on the old floorboards of the dormitory. I could smell the floor polish, and hear the boards squeaking as they had for decades. I opened one eye and saw the others were changing out of their pyjamas and into their uniforms as if their lives depended on it. I peered at my watch it was 5.55 a.m. I was not happy.

Why was everyone in such a hurry? I was not used to getting up so early, but I struggled out of bed.

It seemed like I had travelled back in history and was part of a ritual that thousands of children had observed before me. I could not get over how old and immaculate everything was the school and its traditions were impressive.

Abbas, Murphy called from the other side of the dormitory, get up. He gestured to me to hurry. Get up now. I noticed that he and the other children were dressing in only their vests, shorts, socks and sandals; their shirts, ties and jumpers still lay on their beds. They would then grab their handtowels and flannels and rush out of the dormitory. Murphy kindly and patiently waited for me as I dressed, then gestured for me to follow him. I could see that he was desperate to leave, but he took his duty as my uncle very seriously; it was his responsibility to look after me.

Murphy led me at a brisk walk to the communal washroom. Ten feet away the smell of bleach hit me, and the bright walls shone in the thin dawn light. Everyone was hurriedly brushing their teeth and washing their faces and armpits with their flannels. I had never washed my armpits with a flannel before; I did not understand why they didnt just take a shower. As strange as it seemed to me, I did as the other boys did, although they took no more than three minutes to wash themselves. Once again Murphy had long finished by the time I was done. He said something to me, which I did not understand, so he gestured for me to follow him.

He led me back upstairs to the dormitory where everyone else was busy putting on the rest of their uniforms at an alarming pace. I had never seen people change so quickly. I was doing up my shirt buttons when I noticed the tricks the other children were using to dress faster. They had all left their shirts buttoned the night before and pulled them off over their heads; their belts were still in their shorts and their clothes were laid out in a way that allowed them to dress as quickly as possible. This whole process was a science. I knew I had to catch up fast.

As soon as they finished dressing, they pulled back their sheets, blankets and duvets, then stood to attention at the foot of their beds in silence, awaiting instruction from the head of dormitory, which in this case was Alan. Alan was in the fifth form and would be transferring to a high school the following year. He was also a prefect. Only the previous day I had seen him embarrass Smith and Haynes by making them stand up before Mr Griffiths had come in for tea.

I was the last to be ready. Alan looked at me and then at his watch. He murmured something, and although I did not understand the words, I understood that I would have to be quicker in the future.

Lead on, Humphries, Alan said in a disciplined way. Humphries was in the year ahead of me. Goofy-looking, with a slip-in crown for one of his front teeth and an uncoordinated way of walking, he was sloppy to look at, sloppy in his movements and seemed like an easy target. But I sensed he was a good kid.

I was third in line as we headed back downstairs. I had no idea what was coming and I was too tired to care much.

Alan brought up the rear as our dormitory headed towards the ground floor. A lanky geek shouted something as we passed, and Humphries turned and started shouting back at him. Alan immediately shouted at both boys. I could not understand what was going on, but it was obvious that there was no love lost between Humphries and the other kid.

Murphy turned to me and subtly indicated the lanky boy. Thats Crookshank. He looked grim. Stay away from him hes not very nice. I thought I understood and realised quickly that, like anywhere else, this place had its politics and its power struggles.

I put my head down and tried to forget how tired I was as I followed Murphy downstairs. Soon we were in the assembly room, where I assumed we would wait for breakfast. Alan took charge of the room and I took my place at the bottom of my year, as Id been instructed to do last night when Id first arrived at the school. I hated being last and planned to change that as soon as possible.

Crookshank and Humphries both tried to sit in their respective places but Alan brought them to their feet with a shout. A few others were caught talking and they were also made to stand. After about five minutes the headmaster, Mr Griffiths, walked in. He was wearing his tweed suit, with a pipe in his mouth and a book in his right hand. He took his position at the top of the room and reached for a board covered in neat columns of ticks and crosses. Mr Griffiths looked at each of the boys standing and made a note on the board for each individual then told them to sit down. Crookshank and Humphries glared at each other throughout the whole process. You could see that Crookshank was a sneaky character and was looking for easy prey. I immediately disliked him. As goofy as Humphries looked, he had a kind of charm and though I had no idea what the dispute was about, I had already taken the side of Humphries.

I later learnt that this board contained each boys disciplinary and academic record throughout the term and was displayed for everyone to see. Under the discipline column you could get small xs for minor infractions, called Minor Marks, or a big X for a major infraction, called a Major Minor Mark or MMM. If you did something very bad, you would automatically get one MMM, otherwise you needed to get six Minor Marks to make up one MMM. If you behaved well, and depending on whether your teachers believed you were doing well, you could get a tick, for a Plus Mark. Your Plus Marks would be announced every Saturday night after the end of the school week, and the total for each Colour would be calculated and recorded.

The school was split into different Colours. I was a Green and would remain so for the rest of my Aymestrey school career. Each Colour had boys from all years in it to make it as diverse and fair as possible.

Let us pray, said Mr Griffiths. All the boys leant forward, clasped their hands in front of them and bowed their heads. I had not been brought up in a religious environment and had never really prayed, but I did as everyone else and bowed my head, keeping an eye on Mr Griffiths and my surroundings, just to be sure. Everyone had their eyes closed.

It was not yet 6.30 a.m. and I had already experienced so many firsts. Mr Griffiths opened up the book he was holding and began to read from it. I did not understand a word he said, apart from something about Saint Francis of Assisi. After four or five minutes, everyone murmured Amen. I hurriedly said Amen as well, a little belatedly. I had no idea what I was saying or who I was praying to, but I did not care; fitting in was far more important.

See you in twenty minutes, Mr Griffiths said. The entire school suddenly rose and stood to attention, then Alan began to lead off. As soon as everyone left the common area the boys all dispersed. Murphy pointed, directing me upstairs, and made a sleep gesture to indicate the dormitory when I failed to understand what hed said. All the dormitories were named after birds, and ours was Mallard, although the word meant nothing to me then. I nodded and began to hurry back upstairs. On the way I saw Crookshank gesturing at Humphries again. Humphries was about to turn around when Murphy grabbed him and pulled him upstairs past me.