Contents

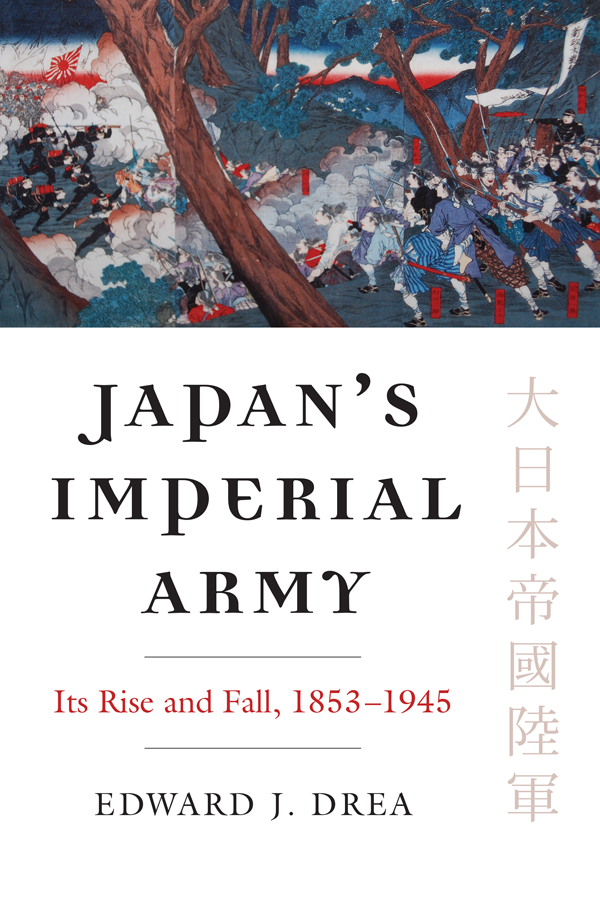

Japans Imperial Army

MODERN WAR STUDIES

Theodore A. Wilson

General Editor

Raymond Callahan

J. Garry Clifford

Jacob W. Kipp

Allan R. Millett

Carol Reardon

Dennis Showalter

David R. Stone

Series Editors

Japans Imperial Army

Its Rise and Fall,

18531945

Edward J. Drea

University Press of Kansas

2009 by the University Press of Kansas

All rights reserved

Published by the University Press of Kansas (Lawrence, Kansas 66045), which was organized by the Kansas Board of Regents and is operated and funded by Emporia State University, Fort Hays State University, Kansas State University, Pittsburg State University, the University of Kansas, and Wichita State University

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Drea, Edward J., 1944

Japans Imperial Army : its rise and fall, 18531945 / Edward J. Drea.

p. cm. (Modern war studies)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 9780-70061663-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 9780-70062234-4 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 9780-70062235-1 (ebook)

1. Japan. RikugunHistory. 2. JapanHistory, Military18681945.

I. Title.

DS838.7.D74 2009

355.0095209034dc22 2009007442

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication is recycled and contains 30 percent post-consumer waste. It is acid free and meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.481992.

Contents

Preface

This brief history of Japans first modern army covers events from the 1850s through 1945. It is an introductory synthesis told mainly from secondary sources, most in the Japanese language. I made use of the many excellent English-language monographs on Japans army but relied more heavily on Japanese-language materials because military history scholarship in Japan has become impressively sophisticated and diverse over the past twenty years. No longer do Japanese historians dismiss the old imperial army with sweeping generalizations. Instead, extensive research in primary documents, the appearance of new evidence, and fresh interpretations of the armys larger role in the context of Japanese society have revised the standard narrative of an army inherently bent on aggression. One goal, then, is to introduce the English-language readers to this new Japanese military history.

I describe major military campaigns briefly and focus on institutional issues arising from those conflicts that shaped the armys strategy, doctrine, and values. These subjects are well known to specialists of modern Japanese history, but a chronologically arranged, balanced English-language account of the army has not previously been available. Overviews of the army tend to be weighted to its twentieth-century performance, especially during World War II, creating a lopsided impression of an army with unique qualities. This narrative, generally divided by decades, gives roughly equal attention to army affairs during the 1880s and World War II. Such an approach offers a balanced perspective on the armys evolution and helps to explain the action and conduct of an institution whose major legacy is suicidal disgrace.

From an ad hoc confederation, the army became the single most powerful institution in the nation. Its leaders wrestled with describing the armys role in the newly unified nation, defining its mission, and designing its values. The intellectual foundations of the institution shifted as the army constantly reinvented itself to fulfill the changing military and cultural imperatives of a transformed Japanese society. In other words, though the outward appearances of the army of 1895 and that of 1925 were similar, the institution was substantially different.

It was not just a matter of adapting western technology or mimicking the Wests pattern of modernization. Japan developed a first-class army with an efficient military schooling system, a well-organized active duty and reserve force, a professional officer corps that thought in terms of the regional threat, and tough, well-trained soldiers armed with appropriate weapons. Changing social and political ideas, personal rivalries, new concepts of warfare, evolving military doctrine, regional geography, and potential enemies and allies shaped the armys place in society. Throughout its existence the army sought its core values in real or imagined precedents and relied increasingly on an emperor-centered ideology to validate it as a special institution in the Japanese polity.

The Japanese soldiers propensity for self-immolation, the militarys emphasis on intangible or spiritual factors in battle, and a fanatical determination to fight to the death became the armys hallmarks. Overemphasis of these characteristics skewed an understanding of strategy, high-level policy, and the armys evolution, especially for the period before 1941. I suggest that historical circumstances shaped Japans first modern army and that international pressures determined the armys options, if not its fate. To deal with common danger, the army idealized traditional values, many of them imaginary but nonetheless offering a vision that a wider Japanese audience understood and shared. The formative days of the army occasionally resembled a B-grade samurai movie replete with wild sword fights in back alleys, assassinations, and murderous blood feuds over the institutions future. These sensational and sanguinary events, much like the later military coup dtats, atrocities, and suicidal banzai charges, inform our perspective of an army run amok, led by fanatics whose blind devotion to the emperor encouraged barbaric behavior. The administrative and operational expansion and development of the army, including its strategy and doctrine, did not make headlines, but this institutional process was decisive in forming the contours of the mid-1930s army, the force that fought in Asia and the Pacific.

The Japanese way of war or style of warfare evolved over seventy years. Subsequent interpretations of the immediate past layered with hoary samurai myths burnished the armys self-image. Layer upon layer of precedent and tradition formed the bedrock of the edifice by 1941. There were, of course, dramatic events that affected the armys course, but it was the accumulated past that shaped the army, narrowed its options, influenced its decisions, and made it the institution that conquered most of Asia.

I am grateful to many people in Japan and the United States for their generous assistance. Professor Akagi Kanji of Kei University responded to my questions with celerity and accuracy. Professor Tobe Ryichi, National Defense Academy, led me through recent Japanese military historiography; and Professor Hata Ikuhiko, the doyen of Japanese military historians, was always helpful in explaining the fine points of Japans prewar army. I am also indebted to the faculty and staff of the National Institute for Defense Studies, Military History Department for their sustained assistance over the years.

Dr. Robert H. Berlin, School of Advanced Military Studies, emeritus; Professor Roger Jeans, Washington and Lee University, emeritus; and Dr. Stanley L. Falk read the manuscript in its various stages. Their constructive criticism, historical expertise, and insightful comments improved the final draft and spared me from numerous errors. Professor Mark R. Peattie, the Walter H. Shorenstein Institute Asia-Pacific Research Center at Stanford University, refereed my draft and made helpful suggestions. David Rennies cartographic and computer talents created the maps.