Richard Macrory - The First Afghan War 1839-42: Invasion, Catastrophe and Retreat

Here you can read online Richard Macrory - The First Afghan War 1839-42: Invasion, Catastrophe and Retreat full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2016, publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The First Afghan War 1839-42: Invasion, Catastrophe and Retreat

- Author:

- Publisher:Bloomsbury Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2016

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The First Afghan War 1839-42: Invasion, Catastrophe and Retreat: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The First Afghan War 1839-42: Invasion, Catastrophe and Retreat" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The First Afghan War 1839-42: Invasion, Catastrophe and Retreat — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The First Afghan War 1839-42: Invasion, Catastrophe and Retreat" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

DEDICATION

To my father Patrick Macrory (19112003) who first inspired my interest in Afghan history

CONTENTS

OVERVIEW

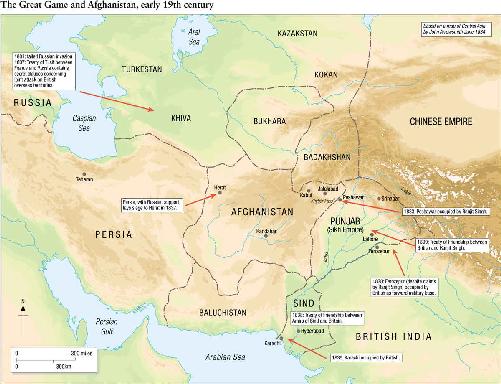

The First Afghan War was a political failure costing thousands of lives British, Indian and Afghan. The British Government wished to protect the north-west borders of occupied India from perceived threats from Persia and Russia, and was intent on ensuring that Afghanistan remained an independent buffer state friendly to its interests. Poor intelligence and the need to keep other allies in the region on side persuaded the government that a regime change was needed the existing ruler Dost Mohammad would be deposed and substituted with a former king, Shah Soojah. It was wrongly assumed that Soojah would be warmly welcomed by the Afghans as a more legitimate ruler, and that the British military could then rapidly withdraw once he had been restored to power.

Three years later, the main British force in Kabul, some 4,500 troops and 16,000 camp followers, was forced by Afghan tribal leaders to negotiate a retreat back to India but, during the march, they were all but destroyed in a little over a week. The Army of Retribution was sent the next year with the sole aim of recovering Britains loss of pride as by then Britain had decided to abandon any further interference in the government of Afghanistan. Dost Mohammad returned to his throne and, despite what had happened, remained largely friendly to British interests until his death 20 years later.

Whatever the weaknesses of the initial political decisions taken, the undertaking in Afghanistan provides many salutary lessons concerning the conduct of a military campaign, some of which have an uncomfortable contemporary resonance. The invasion of Afghanistan by the Army of the Indus almost came to grief through poor logistical planning. There were immense difficulties in maintaining long lines of communication, and it could be said that the expedition reached Kabul more through luck and the lack of organized Afghan resistance than through the use of a carefully executed strategy. Within the East India Company there had been the fairly recent development of a political cadre, and their precise role, and the demarcation of authority between the political offciers and the military, was often unclear, leading to considerable tensions. The subtle nature of Afghan tribal leadership, where authority was based largely on consensus, was difficult for those more familiar with conventional hierarchical institutions to understand, and the British tactics of playing one tribe off against another with offers of bribes was not sustainable in the long term.

Once in occupation, the decision to place small defensive penny-packet garrisons around the country, often in hostile territory with poor communications, was one of considerable risk. The siting and construction of the British cantonments in Kabul appeared to give little thought to any defensive needs, and the British position was not helped by a continual squeeze on financial support from London. In a military crisis, effective leadership is everything, and General Elphinstone, in command of British forces at the time of the initial insurrection in Kabul, was clearly the wrong person to handle the situation. Whatever his personal qualities of humaneness, he was simply unable to make the decisive military response needed. Once the withdrawal of the British forces had been negotiated, the logistical implications of handling the enormous number of camp followers accompanying the force during its retreat was never properly addressed, and proved fatal to any sense of order or effective defence against harassment and attacks.

The British military could still win in set-piece battles but, when Afghan forces used guerrilla tactics, the British were highly vulnerable. Conventional responses such as forming defensive squares were largely futile in such situations. However, it would be wrong to conclude that the British could never employ an effective military response to this type of warfare. General Pollock, in command of the 1842 Army of Retribution, demonstrated this with his focus on meticulous logistical planning, and his effective tactic of crowning heights in hostile mountainous territory to attack the Afghans from the rear and above. From a military perspective, the loss of a single brigade during the retreat from Kabul might be considered a serious but sustainable loss 24,000 French were killed at Waterloo and 19,000 British on the first day of the battle of the Somme. However, this was the first time that such a large professional British force had been humiliated by an apparently unsophisticated and largely uncoordinated enemy. As such, the event assumed tremendous symbolic significance, and the destruction of the British army as it became known revealed potential weaknesses in British colonial structures that had hitherto been unapparent.

THE STRATEGIC CONTEXT

TRIBALISM AND CIVIL WAR IN AFGHANISTAN

By the time the British began to have serious contact with Afghanistan in the early 19th century the country had experienced over 30 years of what was effectively civil war between rival factions. This internal conflict involved an extraordinarily complex array of shifting alliances and power bases, often within the same core families. However, only 50 years earlier the Afghan empire under Ahmad Shah Sadozai had been one of the largest states in the Middle East, and at the height of his power in the mid-18th century he controlled parts of present day Iran, Kashmir, the Punjab, Sind and Baluchistan. However, it is questionable whether Afghanistan could ever have been described as a centralized state under a unifying monarch, certainly in the European sense.

Tribalism was and remains a distinctive feature of the country. The majority of those living in Afghanistan were Pashtuns, who themselves were members of differing tribes, but other important groups existed including Hazaras, Uzbeks, Tajiks and Nuristanis. Mountstewart Elphinstone, who had made the first visit to Afghanistan on behalf of the East India Company in 1808, provided a mass of detailed information in some nine volumes about the nature of Afghan society and politics, which later formed a bedrock of information for those deciding the direction of British policy in the region. He likened the tribes to Scottish clans, but the analogy, though superficially attractive, was misleading. Notions of clan leaders based on lineage and land ownership did not reflect the far less hierarchical nature of Afghan tribes where tribal chiefs largely maintained their position by their ability to secure and distribute wealth rather than by simple birthright.

Ahmad Shah came from the Sadozai family, who were part of the important Pashtun Durrani tribe. They had gained support from other tribal groupings by mounting aggressive foreign campaigns, and had secured a personal bodyguard of Qizilbash, who had originated in Iran. The Qizilbash were never fully integrated with Afghan society, living largely in a distinct enclosure within Kabul, and later becoming key administrators under subsequent rulers.

By the time Ahmads grandson, Shah Zaman, succeeded to the throne in 1793 the stability in Afghanistan was in decline, exacerbated by the traditional practice of polygamy leading to the dominant families having large numbers of brothers and half-brothers some 21 in the case of Shah Zaman all vying for power and influence. Key rivals to Shah Zaman in the years that followed were his brother Shah Soojah, whom the British were later to support as the legitimate ruler of Afghanistan in the 1839 campaign, and his half-brother Shah Mahmud.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The First Afghan War 1839-42: Invasion, Catastrophe and Retreat»

Look at similar books to The First Afghan War 1839-42: Invasion, Catastrophe and Retreat. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The First Afghan War 1839-42: Invasion, Catastrophe and Retreat and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.