EUMENES Publishing 2019, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

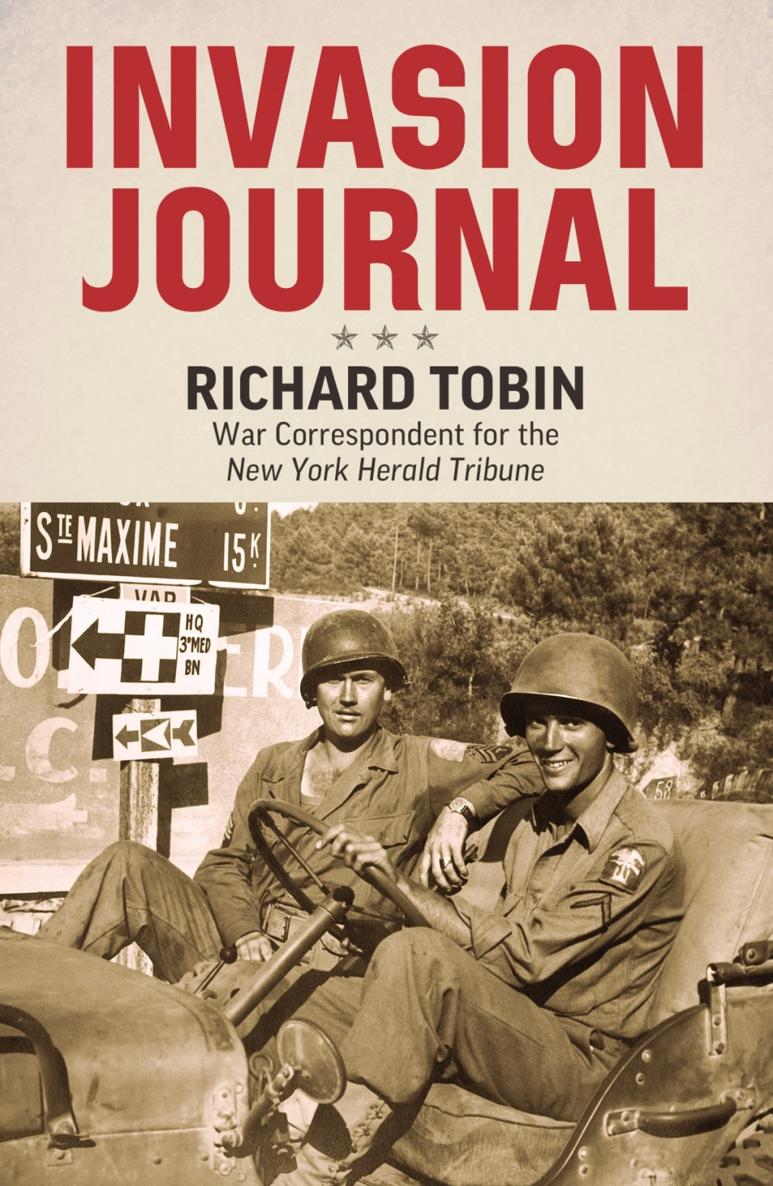

INVASION JOURNAL

War Reports from England and France, April-August 1944

By

RICHARD L. TOBIN

War Correspondent for the New York Herald Tribune

Invasion Journal was originally published in 1944 by E. P. Dutton & Company, Inc., New York.

* * *

TO THE PEOPLE OF LONDON

April 1944

Port of Embarkation, U.S.A., April, 1944

The night river is oily beneath the lights. The black oil fractures quicksilver light paths again and again, yet the lights are stronger; they never disintegrate for all the shimmering. The face of a clock over the river is so darkened that the numbers have disappeared, but I can tell the time anyway, from the position of the hands. At least I think I can, for I am not absolutely sure which is the long hand and which the hour. Yet it must be one oclock; Sylvia and Rusty drove me to the pier at nine, and I was hours through customs, immigration, medical examination and briefing. The look on her face when I kissed her told me how serious this is going to be and what it means to her.

It is far easier for a man to face danger or pain himself than for someone who loves him but cannot be there, cannot feel and share the actual pain. Six months, nine months, a year, possibly never to see her again, or she me; she, the little person I know so well and have slept with, lived with, loved with, had fun with, talked with, thought with, hurt with, argued with, shared everything with, winter and summer, day and night, for seven years. And now she cannot be allowed to go with me on this great adventure. Parting carries terrible hurt, vagueness, an emptiness I feel already, though the great ship and her precious cargo are still tight to the pier. There is something of the lightheadedness of hunger about parting. At least I will be busy, seeing a new world, a world I never made; but it is most grossly unfair to her to be left behind and alone. Even Mark is no compensation at his age. To Mark it is all uniforms and medals. There is none of the reality of hurt about war in the mind of a child. There are only the medals and uniforms.

I hesitated to tell Mark I was going overseas. We had been so close so long. Finally I knew it had to be done. So I told him where I was going, and why. He took it calmly enough. He asked if I would be in uniform. Oh, yes, I told him, in an officers uniform. Then Mark wanted to know: If you get wounded will you get the Purple Heart? Why, I said, after the shock, I suppose so. Ill get any medal I win. Ill be in the Army, in uniform. If Im wounded Ill get the Purple Heart. Yipppee! said Marcus. Oh, hell be all right.

But I wish for Marks sake that I had a rank. He wants me to have something he can boast about. I will be an assimilated captain, but how can you tell your adoring son that? A war correspondent is below a private and above a general. Thats good. I shall have to remember that in conversation. Now, theres a girl on the deck over there, one of a group going to London for the State Department. Shes wearing what looks like miniature captains bars on her lapel. I wonder if shes going around with a captain, or two first lieutenants?

The anaesthetic effect of custom is beginning to wear off, leaning here against the rail, seeing the burdensome troops move inside our great ship, which has no end of appetite. They have been loading since mid-morning. We will sail with the tide, around four, unless some railroad fails its schedule. But it wont. No gongs or shouting, All ashore thats going ashore, to announce our going. No splendid, gigantic whistle in the night air. When we are loaded we will sail, as quietly as floating wood. Goodbye, Rusty, Mark; goodbye, my very dearest. Goodbye from me to every one of those left ashore by the thousands of men in uniform now inside our ship, on the oil-black river.

At Sea, April

We are virtually lying to in fog somewhere off the North American shore. Our engines have been rung off and the helmsman has been relieved after a harrowing night. In war, one does not use a foghorn; yet we are in the convoy, lanes and collision is a momentary threat. The bows of one freight ship after another, bound empty for America, can be seen emerging from the fog, sometimes as close as one hundred and fifty feet away. The ghostly ships come from all angles. The bows of one are heading this minute for the starboard quarter of our great ship; but fortunately we are a large enough vision that we can be seen in time, if the engines are rung slow or rung down altogether. Although neither we nor they can use a horn, we do use deck bells that are to be rung for fog. Here comes another in the westbound convoy, at right angles to our starboard stern. Now, that skipper should have sounded for fog, for he is improperly under way in fog. If he had been further amidships he might not have been able to avoid us and our precious human cargo. Even one day out, the ocean water is too cold for survival for very long.

Once this evening I could hear our own engines suddenly reverse, and the great ship heel to port like a Queens-bound subway train at rush hour. I saw nothing, and it is possible that the lookout saw nothing, except an illusion of shapes in the thickened atmosphere. Our bell now rings continuously for fog as our engines are rung half-ahead. The Master has been here long enough. Idling troop ships are like sitting ducks to hunters. But where a hunter wont shoot a sitting duck, a U-boat or a German will shoot at anything. Im glad the Captain has made up his mind to go along despite the fog and the counterconvoy. The fog has been our first adversary.

At Sea, April

What has shaken me most these first hours aboard this brimming transport ship? I think it has not been the personal dangers of war, nor the fears and dreads of black adventure, the unknown paths ahead, or even the fact of war itself. After many years of comfortable married life, I am certain that it is the complete lack of privacy that strikes me above all the other events and embroideries. I suppose that nowhere on earth is there as little privacy as aboard one of the largest troop transports. I am a serial number among serial numbers. No one really cares if I am seasick or homesick, or uncomfortable. I am beginning to understand the words, Every man for himself. What man fights for on earth is really not fortune or fame, but the right to privacy. This right I have now abrogated, or it has been abrogated for me.

I try to make something of myself so that I shall enjoy privacy, privacy coming from independence, and independence the child of labor and earnings. At thirty-three, with a wife and child, I have unknowingly secured privacy, or I had until this voyage began. I suppose that no one truly knows anything until it happens to him. No more can one imagine the actuality of pain in another. He can sympathize and help, but he cannot feel the pain until the stimulus strikes him. So in this terrible overcrowding, especially below decks where the G.I. Joes are herded like cattle, I am beginning to learn what privacy meant to me and what it will mean when the war is past. Here aboard this once great passenger liner, a British ship of magnificence and expanse, where in peacetime a few hundred passengers would have slept, thousands now not only sleep, but eat, and stand and wait. If there is one thing a troop transport is apt to teach a man it is how to wait; for me there is a sharper lesson. I now have learned a specific price on a golden commodityprivacy.