ISLAM IN PAKISTAN

PRINCETON STUDIES IN MUSLIM POLITICS

DALE F. EICKELMAN AND AUGUSTUS RICHARD NORTON, SERIES EDITORS

A list of titles in this series can be found at the back of the book

Islam in Pakistan

A HISTORY

Muhammad Qasim Zaman

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON & OXFORD

Copyright 2018 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

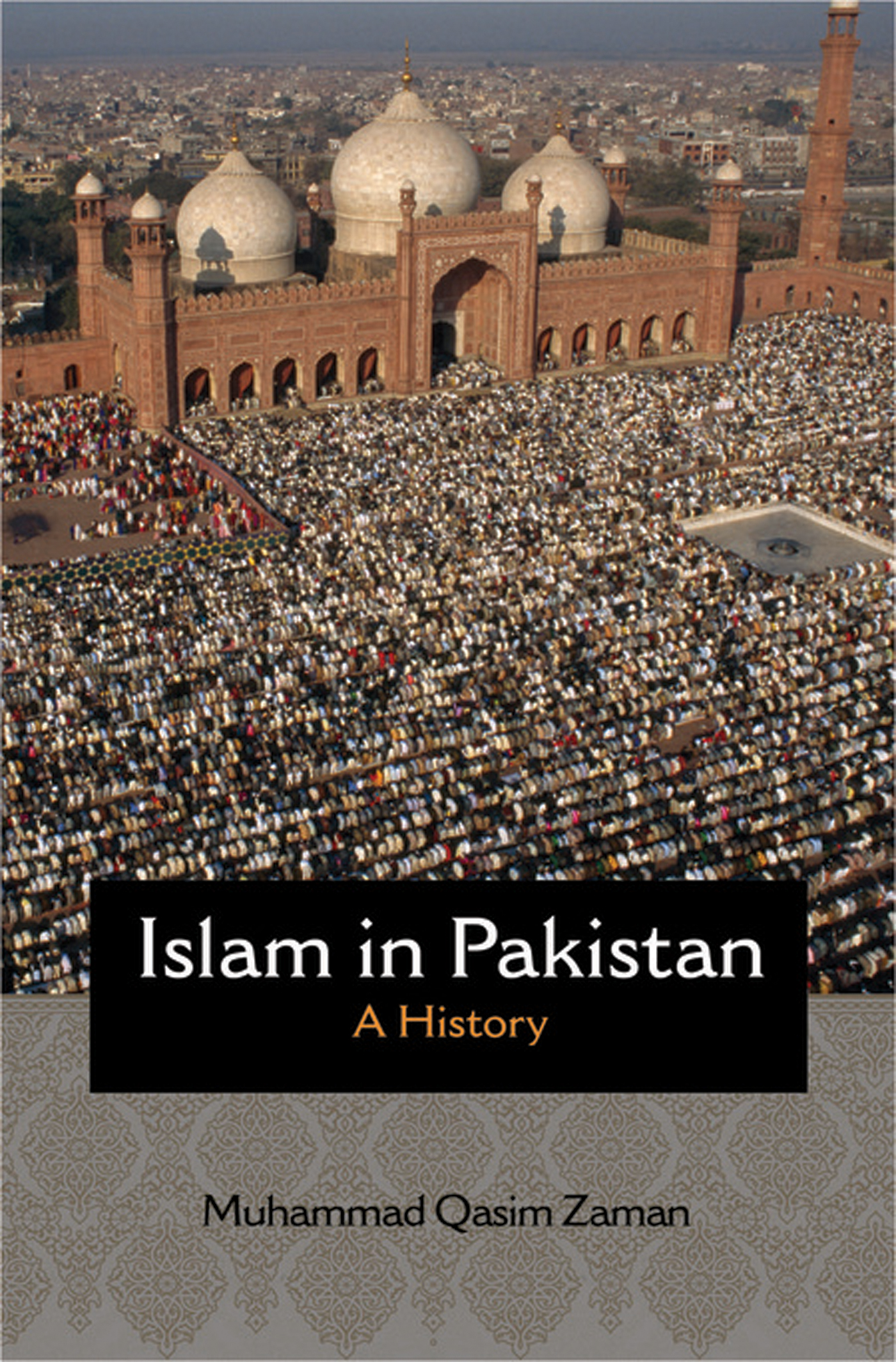

Jacket photograph: Ed Kashi, 1997 / National Geographic Creative

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Zaman, Muhammad Qasim, author.

Title: Islam in Pakistan : a history / Muhammad Qasim Zaman.

Description: Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press, [2018] | Series: Princeton studies in Muslim politics | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017039100 | ISBN 9780691149226 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: IslamPakistanHistory. | Islam and statePakistan.

Classification: LCC BP63.P2 Z36 2018 | DDC 297.095491dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017039100

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Miller

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Shaista

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

MANY PEOPLE AND INSTITUTIONS have assisted me in the course of my work on this book. I am grateful above all to Shaista Azizalam and to our children, Zaynab and Mustafa, for continuing to enrich my life with their love and companionship. I owe a great debt as well to my sister and brother-in-law, Rabia Umar Ali and Umar Ali Khan, for hosting my visits to Islamabad with their unmatched hospitality and for facilitating my research in Pakistan. I would not have been able to carry out my work without their help. My nephews and nieces, tooValeed and Moosa, Ayesha, and Rahem and Samahhave been the source of much joy and hope, for which I am grateful.

I would like to thank Megan Brankley Abbas, Sarah Ansari, the late Zafar Ishaq Ansari, Michael Cook, Eric Gregory, M. kr Haniolu, Robert W. Hefner, Husain Kaisrani, Muhammad Saeed Khurram, Sajid Mehmood, Steve Millier, Hossein Modarressi, Gyan Prakash, Ali Usman Qasmi, and Qamaruz-Zaman for their help with accessing research materials and, in several cases, for answering my queries and providing valuable feedback. The writing of this book has been made possible by a grant from the Guggenheim Foundation as well as research leave and other support from Princeton University. I am much indebted to these institutions. I wish also to thank the library staff at the various places in Pakistan, India, the United Kingdom, and the United States where I have carried out my research. In particular, I wish to thank David Magier, other members of the staff of the Firestone Library at Princeton University, and all those working behind the scenes at its interlibrary loan and Borrow Direct offices for attending to my requests with great courtesy and efficiency. My students, undergraduate as well as graduate, have been instrumental in helping me try new approaches, deepen my knowledge, and explain things better. For this I am very grateful.

Some of the material on which this book is based was presented as lectures at Boston University; the Davis Center for Historical Studies at Princeton University; Northwestern University; the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London; the University of Chicago; and the Yale Law School. I thank the organizers of those events for their invitationsin particular, Owen Fiss, Robert Gleave, Brannon Ingram, Anthony Kronman, Philip Nord, Tina Purohit, Mariam Shaibani, Zayn Siddique, SherAli Tareen, and Amir Toftand their audiences for their comments and questions. I also thank Indiana University Press and Cambridge University Press for permission to use, in revised form, some of the material I have previously published as the following articles: Islamic Modernism, Ethics, and the Shari`a in Pakistan, in Robert W. Hefner, ed., Shari`a Law and Modern Muslim Ethics (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2016); Pakistan: Shari`a and the State, in Robert W. Hefner, ed., Shari`a Politics: Islamic Law and Society in the Muslim World (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2011); and The Sovereignty of God in Modern Islamic Thought, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 3rd ser., 25 (2015).

Over the course of many years, Fred Appel, my editor at Princeton University Press, has offered support, encouragement, and much astute advice. It has been a privilege and a pleasure to work on this and other projects with an editor of such remarkable abilities. Feedback from the outside readers has helped improve this book in some important ways; I am deeply appreciative of their careful and sensitive reading and their counsel. I would like to also thank Sara Lerner, who has shepherded this book through production with her characteristic thoughtfulness, skill, and efficiency. I am especially glad to have had the opportunity to work with her a second time. I wish as well to acknowledge Thalia Leaf, Theresa Liu, and many others at Princeton University Press for their assistance with various matters related to this book. I owe a special debt to Jennifer Harris, whose keen eye and expert advice in copyediting the manuscript have helped turn it into a much better book.

Shaista has long been my mainstay. She has patiently fostered the conditions that have allowed me to bring this work to fruition. As a small token of my gratitude for this and for much else, I dedicate this book to her.

A NOTE ON TRANSLITERATION, SPELLING, ABBREVIATIONS, AND OTHER CONVENTIONS

THIS BOOK USES a system of transliteration that often reflects Urdu pronunciation of Arabic and Persian words and names. In cases where a proper name is spelled by the person concerned in a particular way in English, that spelling has usually been retainedhence, Liaquat Ali Khan rather than Liyaqat `Ali Khan; Abdul Hakim rather than `Abd al-Hakim; Ayub Khan rather than Ayyub Khan, and so forth. In some cases, however, the English and the Arabic spellings of a name have had to be distinguished from each other: thus Mawdudi when referring to the Urdu titles of his books and Maududi when citing the English translations.

With the exception of the ` to signify the Arabic letter `ayn (as in `Umar or shari`a) and to represent the hamza (as in Quran), diacritics are not used in this book. The hamza itself is used when it occurs within a word (as in Quran) but not when it occurs at the end (thus `ulama rather than `ulama). With the notable exception of the term `ulama (singular: `alim), the plural forms are usually indicated by adding an s to the word in the singular, as in madrasas (rather than madaris) or fatwas (rather than fatawa). Certain terms that occur repeatedly in the book, such as shari`a and `ulama, are not italicized. Other Arabic and Urdu words are italicized at their first occurrence, but usually not afterward. When the fuller version of an Arab name is not being used, I also dispense with the Arabic definite article al- (for example, Fakhr al-din al-Razi but subsequently Razi).

Unless otherwise noted, translated passages from the Quran follow M.A.S. Abdel Haleem, The Quran: A New Translation (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2004), and, less often, A. J. Arberry,

Next page