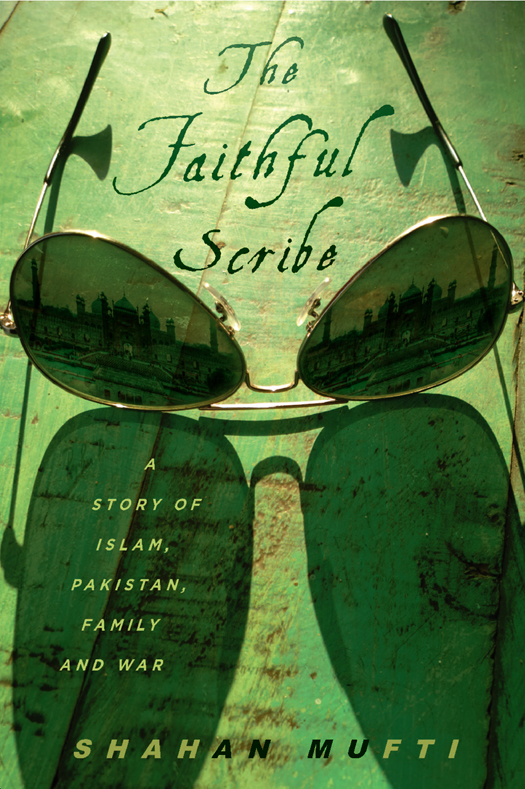

Copyright 2013 Shahan Mufti

Production Editor: Yvonne E. Crdenas

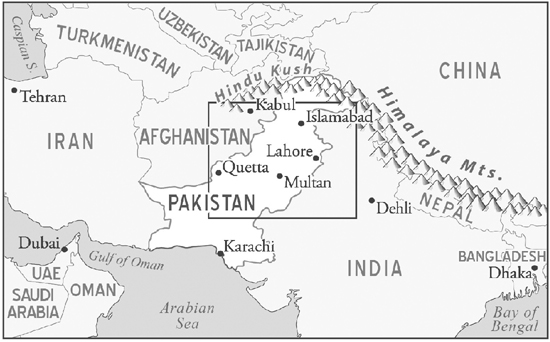

Maps on by Valerie M. Sebestyen.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Other Press LLC, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. For information write to Other Press LLC, 2 Park Avenue, 24th floor, New York, NY 10016.

Or visit our Web site: www.otherpress.com.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Mufti, Shahan, 1981

The faithful scribe : a story of Islam, Pakistan, family, and war / by Shahan Mufti.

pages cm.

eISBN: 978-1-59051-506-8

1. Mufti, Shahan, 1981 2. Mufti, Shahan, 1981Family. 3. Islam and culturePakistan. 4. Islam and politicsPakistan. 5. India-Pakistan Conflict, 1971. 6. PakistanHistory. 7. PakistanBiography. I. Title.

DS385.M83A3 2013

929.2095491dc23

2013000897

Authors Note: This book is entirely a work of nonfiction based on real events. I have drawn facts from my own memory, my reporting of events, which occasionally relied on memories of others about events in their own lives, or their memory of the memories relayed by others. I have also used works of written history that have been recorded, over many eras, by recognized historians from around the world. In all cases, I have strived to be as accurate as possible in portraying events and characters of the past and present.

v3.1

FOR AMMA AND ABBU

Contents

If all the trees on earth were pens and all the seas,

with seven more seas besides, were ink,

still Gods words would not run out.

THE QURAN 31:27

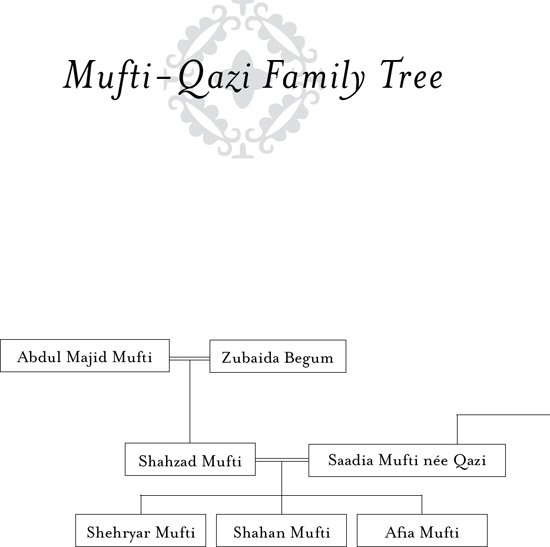

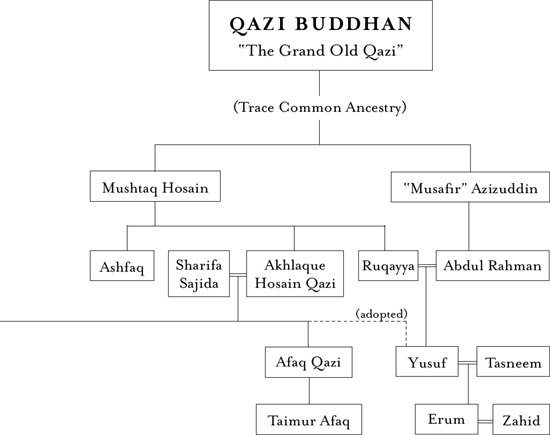

* This family tree includes only names mentioned in this book.

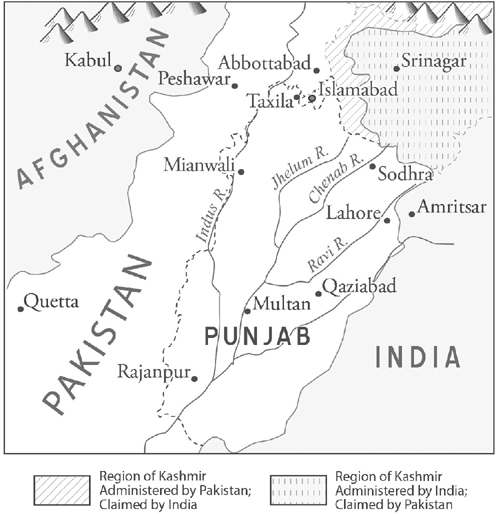

Pakistan and Surrounding Region

The Land of Five Rivers

Home

I F WE MEET at a party in New York you might ask me where Im from. People usually end up asking me that. Its not that Im very exotic looking. I am average height, slim, and I have ambiguously brown skin. I wear those dark-framed glasses that are pervasive in the legions of writers and journalists who find their way into this city, and I have plentiful facial hair that swells and recedes depending on the number of deadlines I am juggling. None of this makes me stand out terribly in New York. This is a city where the trains are filled with people from all countries of the world, each person with his own surprising story. Thats one of the things I love most about being here. What might make you wonder about me is my language, specifically, the way in which I use and pronounce words. At first my American-accented English sounds perfectly natural. You will likely assume that I am American, and you will be right. I am American, and so you might judge it impertinent to explore my ethnic background. But in the flow of conversation, I might use a wordsupper instead of dinner maybethat pricks your ears as unusual. Or I might just launch, with passion, into a monologue about the sport of cricket. Then, spotting the lull in conversation, you may finally lean in and, over the pleasing din of courteous conversation, ask, So, where are you from?

Pakistan, I will reply. Well, my parents were both born in Pakistan. I was born in the American Midwest, but I have shuttled back and forth between America and Pakistan for my entire life. A year here, four years there, five months here, two weeks there; if I sit down to count it all, I might discover that I have split my time equally in the two countries down to the exact number of months. Ill tell you, Im 100 percent American and 100 percent Pakistani. Its true. Both countries and cultures are equally home to me. You might ask me where in Pakistan my family is from. I would tell you Lahore, and explain that it is the heart of the region in Pakistan known as the Punjab. I speak Urdu and Punjabi just as well as I speak English. For this reason, working as a reporter in Pakistan has been easier for me than it is for most other American journalists. And no, no one in Pakistan would think Im from anywhere other than Pakistan.

I know that in your mind you linger on that word: Pakistan. No matter where youve been for the past decade, youve probably heard of this place, and often. You probably recognize the word well. Its a pop of a gunshot in the room. Pakistan! During the past few years you have been bombarded with information, images, ideas about this country, much more than you can recollect at this moment. But there are basic impressions: it is next to Afghanistan; it is next to India; its Muslim; it has nuclear bombs, many nuclear bombs; its the place where a man named Osama bin Laden was finally found. Whatever specific details you can recall are probably more or less accurate. So while I speak, you will be thinking of that Pakistan. But I also am thinking, as I speak to you, about the place that you picture in your mindand to me it looks like a caricature, a dark parody.

Later in the evening, we might find ourselves together again, a group of common friends sitting around a coffee table loaded with empty glasses and half-eaten hors doeuvres. More comfortable and familiar, the conversation might flow more freely now and more honestly. Why is Pakistan such a mess? Its a fair question, but unless you have a few days to talk about this, I will try to point to the kernel of the problem. Pakistan is a unique country, and so it has unique problems. In August 1947, months before the state of Israel was created as a refuge for a nation of Jewish people, Pakistan came on the map as a home for all the Muslims scattered over South Asia. These Muslims were from dozens of different races and ethnicities and they spoke dozens of different languages and dialects. The one hundred million Muslims living in South Asia in 1947 made up more than a quarter of the worlds Muslim population. Millions of Muslims packed up the stuff of their lives and migrated to this new state that hot summer, and Pakistan became the worlds largest Muslim country at the time.

It was a remarkable new state. Most other Muslim countries that had won independence from European colonial rule during the twentieth century came to be ruled by kings or emperors or emirs. But Pakistan, emulating countries in Europe and America, aspired to become a constitutional democracy. Turkey was another Muslim-majority country that was formed as a constitutional republic after the First World War, and it self-consciously modeled itself after European countries as a staunchly secular state. But in Pakistans case there was an important and fateful twist: Pakistan strove to incorporate Islam into its constitutional democracy.