Contents

Guide

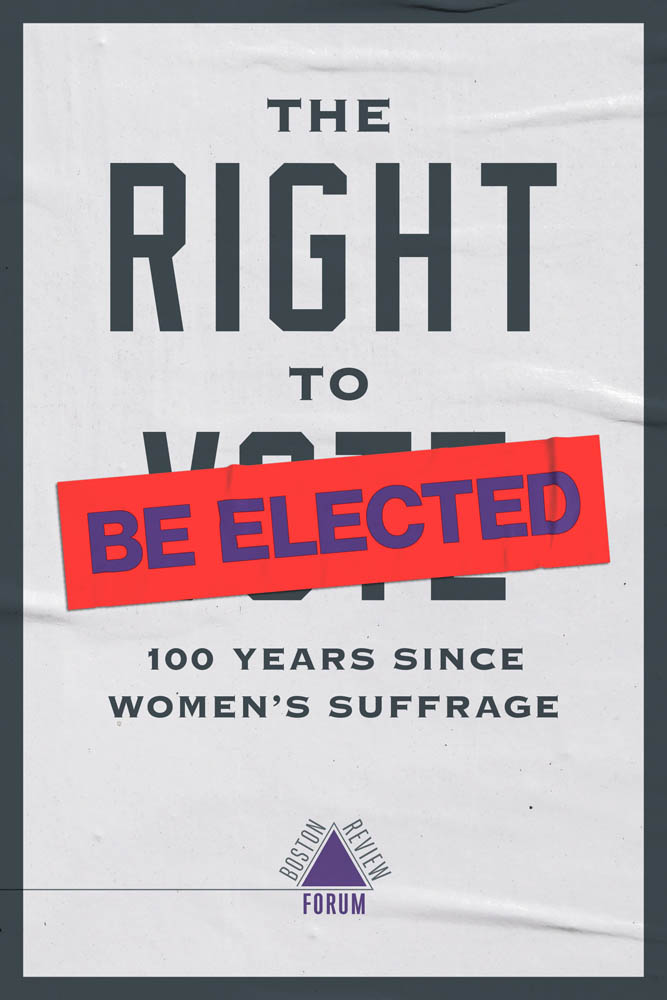

THERIGHTTO BEELECTED

Editors-in-Chief Deborah Chasman & Joshua Cohen

Executive Editor Chloe Fox

Managing Editor and Arts Editor Adam McGee

Senior Editor Matt Lord

Engagement Editor Rosie Gillies

Contributing Editors Junot Daz, Adom Getachew, Walter Johnson, Robin D.G. Kelley, Lenore Palladino

Contributing Arts Editors Ed Pavli & Evie Shockley

Editorial Assistants Carl Denton & Aparna Gopalan

Marketing and Development Manager Dan Manchon

Finance Manager Anthony DeMusis III

Distributor The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England

Printer Sheridan PA

Board of Advisors Derek Schrier (chairman), Archon Fung, Deborah Fung, Alexandra Robert Gordon, Richard M. Locke, Jeff Mayersohn, Jennifer Moses, Scott Nielsen, Robert Pollin, Rob Reich, Hiram Samel, Kim Malone Scott

Interior Graphic Design Zak Jensen & Alex Camlin

Cover Design Alex Camlin

The Right to Be Elected is Boston Review Forum 14 (45.2)

To become a member, visit:

bostonreview.net/membership/

For questions about donations and major gifts,

.

Boston Review

PO Box 425786

Cambridge, MA 02142

ISSN :0734-2306 / ISBN :978-1-946511-53-9

Authors retain copyright of their own work.

2020, Boston Critic, Inc.

d_r0

Contents

- FORUM

- FORUM RESPONSES

- Persuasion, Not Quotas

- Changing Gendered Expectations

- The Battle for Women's Representation Starts in Our Homes

- Race Matters Too

- Solutions Designed for the U.S. Political Context

- The Electability Trap

- Moving History Along

- ESSAYS

- When Quotas Come Up Short

- Dreaming of Democracy: Shirley Chisholm's Political Life

- Save the ERA

- -->

Editors Note

Deborah Chasman & Joshua Cohen

IN THIS DIFFICULT YEAR , we celebrate the hundredth anniversary of women's suffrage in the United States. Paying homage to the suffragists victory securing the right for women to vote, this volume pushes forward the conversation they started, exploring why women's representation in public office here has lagged so far behind other democracies.

Guest editors Jennifer M. Piscopo and Shauna L. Shames describe how suffrage movements around the worldfrom Europe to the relatively new democracies of Latin Americaoften focused not only on women's right to vote, but also the right to stand for office. When these movements succeeded, they embraced the right to be elected as a positive right, enabling nationwide efforts to encourage and actively recruit female candidates, often with quota systems for elected officials or party slates.

In the United States, why hasn't a woman's right to be elected been seen as coequal with her right to vote? And what if we took up the challenge of putting them on the same footing? Responding to Piscopo's forum essay, scholars and advocates of women's political participation consider U.S. culture, the political landscape, the interplay of race and gender, and different electoral strategies for women candidates. But they agree that democracy without women is not democracy.

Other essays in this volume explore a wide range of topicswhether women govern differently, the importance of Shirley Chisholm as a political figure, and the history of the ill-fated ERA.

The Right to Be Elected is not a history of women in politics, nor a primer on strategies to encourage more women to run for (and succeed in) political office. At its core, it simply asks what does gender equity in a democracy look like.

Introduction

Jennifer M. Piscopo & Shauna L. Shames

WHEN COVID -19 paralyzed the globe in April 2020, Donald Trump swaggered about the White House telling falsehoods while New Zealand's prime minister, Jacinda Ardern, held a special press conference to reassure the nation's children. Canny observers have noted that the places with low case numbers and more effective policy responsesfrom Germany to Taiwanare led by women. It is no accident that these states are also strong and wealthy democracies, with capable bureaucracies and high levels of institutional trust. Though women leaders historically have governed countries both rich and poor, democratic and nondemocratic, today women head some of the world's most influential democracies.

In the United States, by contrast, presidential contender Elizabeth Warren made scant headway with her policy wonkiness, losing the Democratic Party nomination. Men's dominance of the country's highest political office will remain intact, even as many women chip away at the lower levels. In an iconic 2017 image of the Trump administration, an all-male, all-white group of Republican lawmakers discuss repealing the Affordable Care Actincluding benefits for pregnancy and maternity care. The photo neatly captured the exclusionary politics that angered so many women. This exclusionalong with feelings of threat, urgency, and angerdrove a record number of women to run in the 2018 midterms. Two hundred and fifty-seven women (including an unprecedented number of women of color) contested races for the House and Senate, seventy-five more than in 2016.

This surge in women candidates was seen as a good thing by 61 percent of Americans. Despite the sexism many women candidates still face, and the failure to elect a woman to the presidency, the U.S. public seems enthusiastic about having women in elected office. This preference echoes an increasingly global sentiment that women's political representation is key to the proper functioning of democracy. Around the globe, more women in office is associated with greater trust in government.

The converse is also true. Recently, Piscopo and colleagues Amanda Clayton and Diana Z. OBrien showed that women's absence from government makes Americans view government as less democratic. When presented with the options of an all-male legislative committee and a gender-balanced committee, respondents perceived the manel to be less fair, less trustworthy, and less legitimate. This preference held even when the manel wasn't deliberating on women's issues. Even Republicans and especially men preferred the gender-balanced panel. Despite our political polarization, it seems we can all agree that women's exclusion from decision-making bodies is undemocratic.

And yet, in the United States, which this year celebrates the centennial of women's suffrage, little attention has been paid to women's officeholding as a political right, not to mention the benefits that follow for society and politics. A nearly exclusive focus on voting rights leads to an unbalanced perspective about what constitutes democratic representation. By contrast, the Freedom House's Freedom in the World ranking system includes both whether adult citizens enjoy universal and equal suffrage and whether women are allowed to register and run as candidates.