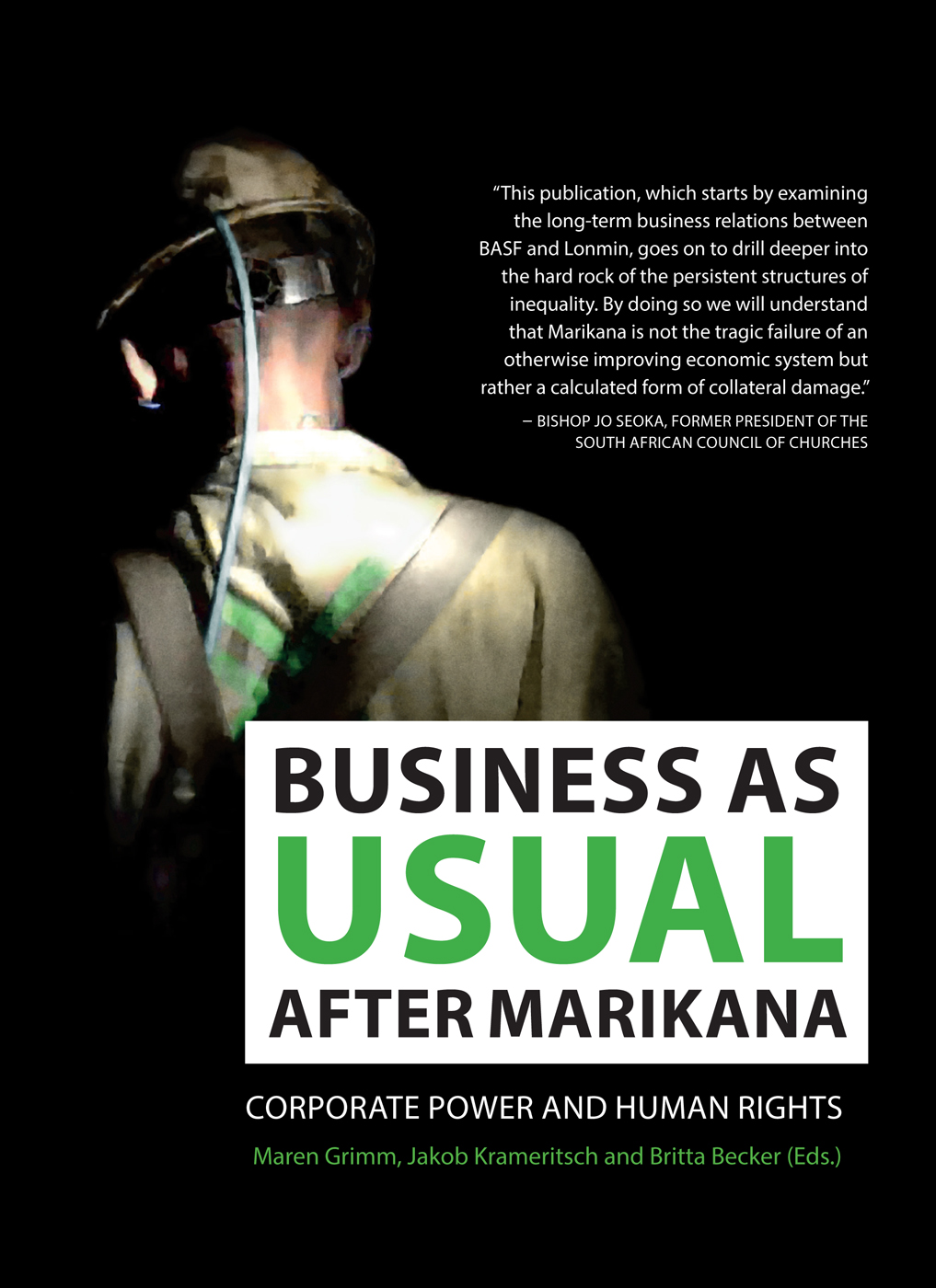

From Marikana to Ludwigshafen: Along the platinum supply chain

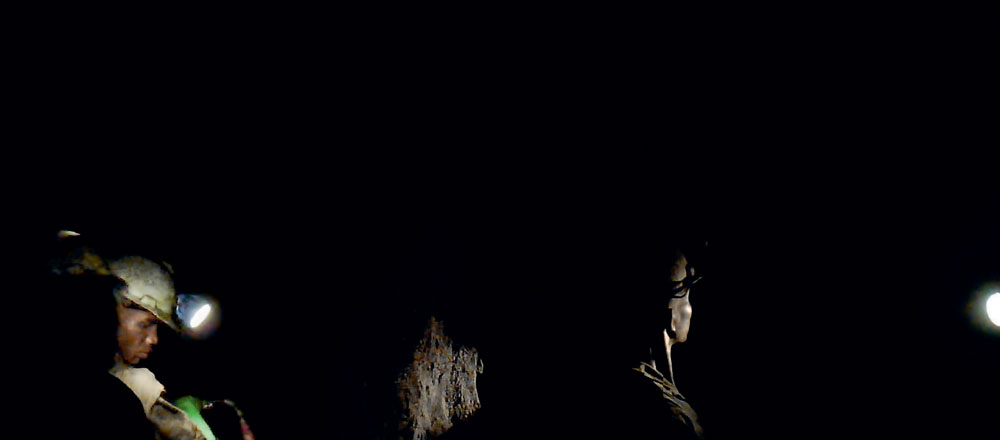

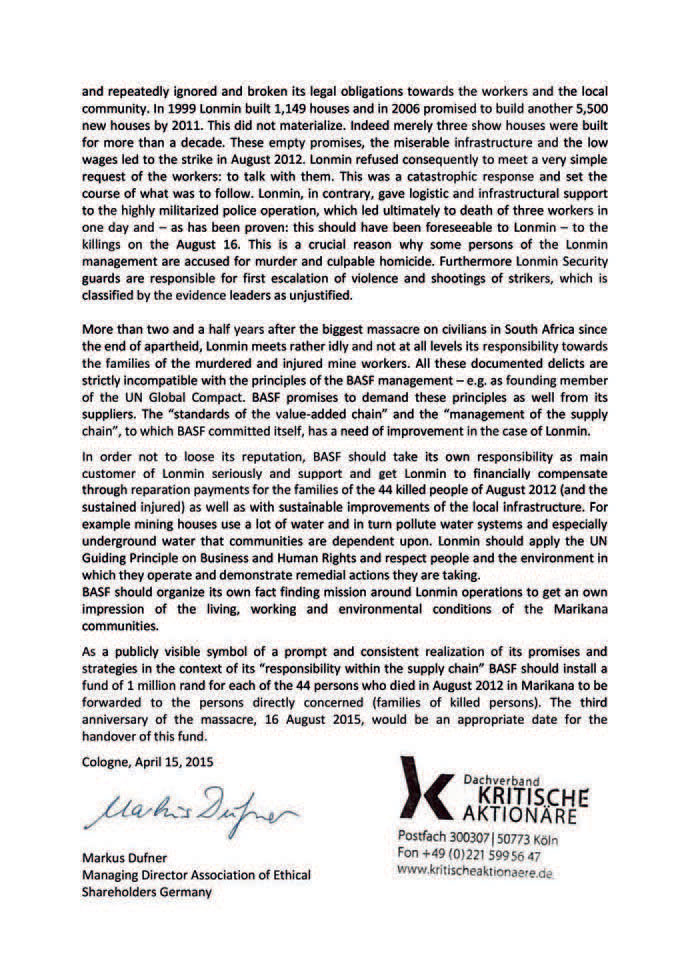

Pictures secretly taken in the Marikana platinum mines of the underground work at a depth of approx. 1,000 meters. The only lighting in the shafts is the workers headlights.

Day and night: View from the informal settlement Nkaneng looking onto Lonmins neighbouring Base Metal refinery. In the foreground on the left: one of the few measures taken after the Marikana massacre. In 2016 Lonmin ordered a large quantity of toilet houses, which can be placed on top of a hole in the floor.

Water is supplied to the informal settlements around Marikana through water tanks or individual, collectively used taps. This water point close to Nkaneng was installed in 2016. Women do the reproductive labour. In the background is one of the numerous ventilation systems for underground shafts.

Tree in Marikana. In the background: a transformer station and power lines that supply Lonmins premises with electricity. Most of the inhabitants of the surrounding settlements, the Lonmin workers, have no electricity connection.

Counter motion of the ethical shareholder association Dachverband der Kritischen Aktionrinnen und Aktionre Deutschlands not to grant discharge of liability to the Executive Board of the chemical group BASF for the financial year 2014, as it did not fulfil its responsibility in the supply chain in the case of Lonmin. Submitted on 15 April 2015 to BASFs shareholders meeting on 30 April 2015 in Mannheim.

Bishop Jo Seoka, representative of Marikanas miners, speaks at the BASF shareholder meeting in Mannheim on 30 April 2015. To his left is Markus Dufner, Managing Director of the Dachverband der Kritischen Aktionrinnen und Aktionre Deutschlands.

Late summer 2017 on the Willersinnweiher beach, a popular local recreation area in Ludwigshafen. Between the trees: a view of BASF operating under full capacity.

FOREWORD

Bishop Jo Seoka

The mining industry has always been the backbone of South African economy, and it still is. A healthy and sustainable mining sector accordingly should form part of the focus of our efforts to heal this country and its people. Nevertheless, the history of mining in South Africa has been and continues to be characterised by oppression and exploitation of the workers under the policy of the migratory system. Most of the miners are people with no education or a very elementary one that helps them take instructions from the employer. The new dispensation of 1994 did not assist much in changing the conditions at the mines, as there is still dissatisfaction with living and working conditions and with wages.

The Bench Marks Foundation, whose chairperson I have been since it was founded and launched in 2001, has been researching the Platinum Belt in the North West Province of South Africa. In 2003 we started to examine the transnational corporations that have operated in South Africa since 1994. In 2007 we produced the first report in a series popularly known as the Policy Gap, which focused on mining corporations such as Lonmin, the main platinum supplier of BASF, the biggest chemical enterprise worldwide, which is the focus of this book.

The Bench Marks Foundation had predicted mayhem on the Platinum Belt and around Lonmin. We warned the mining houses that a more difficult situation could be expected. Already in 2011, Lonmin was experiencing community protests resulting from frustrations and anger at the mining houses failure to heed the communitys demands, such as the provision of employment opportunities for the local youth and the improvement of the appalling living conditions which, among other things, cause chronic sicknesses among children.

Therefore, there was already tension around the Platinum Belt and workers were talking about fighting for their labour to be compensated accordingly, since they worked under very tiring and dangerous conditions. For a period of twenty years, super-profits involving a return on investment of 30 per cent, way above the world benchmark of 8 per cent, enriched the shareholders and investors but impoverished the workers and surrounding communities.

In 2011 we decided to revisit the first edition of the Policy Gap report and review whether there had been any changes in the behaviour of these corporations towards communities, and whether the mining houses had taken up any of the recommendations of the Bench Marks Foundation. Lonmin was one of the mining houses whose challenging problems were highlighted in the report such as high level of fatalities, poor living and working conditions for the miners, negative impact on small-scale farming, outsourcing of workers and environmental destruction.

We released a damning follow-up report on 14 August 2012. In a press release we outlined the outcomes of our report: The platinum mining companies appear on the surface to be socially responsible, respectful of communities and workers and contributing to host community development. Nothing can be further from the truth. Two days afterwards, on 16 August 2012, 34 mineworkers on strike for better living and working conditions were brutally killed by the South African police near the Lonmin-owned platinum mine in Marikana.

On 9 August 2012, the rock drill operators (RDOs) at Lonmin had begun their strike action to demonstrate their unhappiness with the mine managements refusal to negotiate a living wage. The RDOs led a march to Lonmin Platinum Division where the offices of Lonmin are located. There they were met with hostility from the mine management, who threatened the strikers with dismissal. In the following days, shooting was reported by various media television, radio and print. People were killed, both mineworkers and policemen.

By 16 August, tension and conflict had escalated and there were fears that conflict might break out between the police and the striking miners. It was on this day that I decided to visit Marikana because it was within my episcopal jurisdiction and at the time I was also the president of the South African Council of Churches. My intention was to find out how we could defuse the volatile atmosphere that could lead to more people being killed. This I believe was prophetic since on that very day in the afternoon the police shot and killed 34 unprotected workers. The massacre happened when I had just relayed the message to Lonmin of the need for management to go and address the workers on the