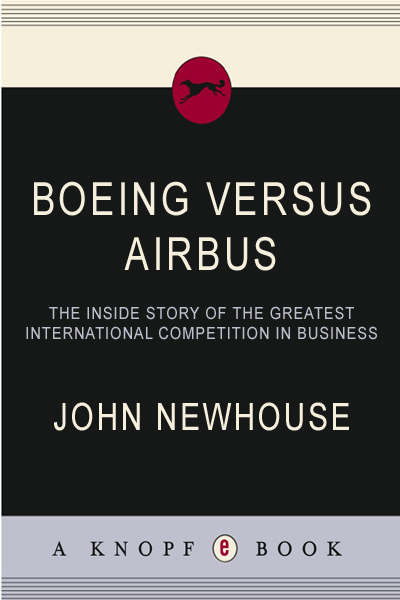

PROLOGUE

Back in the 1970s and early 1980s, four companies divided the turbulent business of making and selling passenger airplanes. One of them, the Boeing Company, was dominant. The other two big American playersthe Lockheed Aircraft Corporation and the McDonnell Douglas Corporationlabored in the wake of their own mistakes. Lockheeds were terminal, and McDonnell Douglas, known in the trade as McDac, hadnt come to terms with reality. The reality was that a small European company called Airbus Industrie, generally known only as Airbus, had abruptly become not just a player but a mortal threat. Simply put, Airbus was eating McDacs lunch.

Although steeply uphill, this business has never lacked bold, entrepreneurial spirits. Many have tried, few successfully. Some of the high rollers never learned to read the market. The airplanes they built were too big or too small, or cost more to operate than airlines were willing to pay. Or the airline market might have moved on. Or the new airplane might have been mated with the wrong engine, or just been unlucky.

An example of bad luck was Lockheeds L-1011, a three-engine, wide-bodied airplane built in the late 1960s and also known as the Tristar. In its time it may have been the best of the double-aisle airplanes, probably the most admired by aerodynamicists. But the combination of bad luck and bad timing victimized the airplane and its maker. The L-1011 had lost $2.5 billion when it was retired in 1981.

Suppliers of these large commercial aircraft (LCAs, as they are known in the trade) have goals that draw on spongy assumptions, political hubris, and industrial savoir faire. They mix great expectations with huge uncertainties. They grapple with uncertainty by dispensing smoke and mirrors. Every transaction becomes the most important until the next one.

Reading the market is largely guesswork. An airline may plan to use a new airplane for twenty, possibly thirty years, but cant predict how many times the market will change direction along the way. In market forecasting, the airline must guess what size bucket (the airplane) will be needed to carry an unknown quantity of sand (the passengers). The supplier guesses when to launch an airplane and must then continue betting that its one that will meet both the short- and long-term needs of the unforgiving market.

The decision to build a new LCA alerts boards of directors and shareholders to impending deficits, big ones. Indeed, the costs of any such venture can amount to betting the company, literally. A single deal with one airline can determine the fate of an airplane on which billions of dollars have been invested. And the returns, if any, lie far ahead. The break-even point of a new program is invariably a made-up number and is rarely, if ever, pinned down.

No airline will pay the list price for an airplane, if there is such a thing. The massive discounts offered to launch customers tend to establish the price, or come close to establishing it. The business is tougher than most, largely because its more about instinct and psychology than economics. When airlines feel confident about the future, they order airplanes. When they lose confidence, they stop buying. In good times, the airlines purchase too many airplanes, but all too often they take deliveries in the economys troughs, which always lie just aheadwhen they may cancel or postpone deliveries. Timing is the key variable for buyer and seller.

Ironically, McDac, or more exactly its founder, James McDonnell, blundered by refusing to build the very airplanea small, twin-engine wide-bodythat Airbus did build and that allowed this European upstart to acquire a foothold in the global airline market. The A300, as Airbus called its first airplane, was an ideal fit for a hole in the market that all the suppliers could see and that any one of them could have filled. But Mr. Mac, as he liked to be called (by family members as well as others), decided to compete with Lockheed by building not what the market wanted but his own three-engine wide-body. He called it the DC-10. It appeared indistinguishable from the L-1011 but was inferior in ways that mattered. Indeed, the DC-10, an ill-conceived and rather hurried project, was to acquire some notoriety. Building it was a foolish move. The market for these look-alike aircraft wasnt there; predictably, they killed each other.

They did more than that. Neither of the two companies would build another LCA, and at different speeds, each would abandon the commercial end of the business. McDacs exit meant the demise of a truly great company, the Douglas Aircraft Corporation. At one time, it had been the most respected of LCA suppliers, and had the confidence of more of the worlds airlines than either Boeing or Lockheed. In the early days of the jet age, Douglas had been Boeings only peer, but the companys leadership had also become steadily less rigorous and disciplined in holding down costs. By 1966 it had lost the confidence of its bankers and become a takeover target for Mr. Mac, who saw every reason to join his highly profitable military aircraft business with the worlds most illustrious LCA producer.

The marriage never worked. Mr. Mac foolishly tried to bend Douglas to his ways of making and selling a very dissimilar product line. His ignorance, judgment, and timingall threetook the venture straight downhill. Douglas had been the airlines preferred producer of propeller-driven LCAs, and its first jet-powered modelsthe DC-8 and DC-9were revered, but Boeing had invested more heavily and judiciously in jet airliners and had begun to take control of a burgeoning market for them.

A N EXISTENTIAL PENDULUM governs the fortunes of the companies that struggle to gain an edge in this unsteady business. At one time, the advantage might have drifted now to Douglas, now to Lockheed, now to Boeing. Then, in the years between 1985 and 2005, the gestalt changed. As the weaker players fell away, the focus shifted to a hardier but dissimiliar pair: mighty Boeing and the arriviste Airbus.

For much of that time, Boeing held a commanding lead, its supremacy not really contested. Nevertheless, by the mid-1990s, if not before, the gallery could see this twosomes fortunes start to converge, as Boeing, complacent and risk averse, became less committed to the fundamentals of its tradebuilding new and better models and treating airline customers with care. Airbus, on the other hand, was stressing the fundamentals, gaining credibility, making a dent in the market, and even beginning to scent blood. With the passage of not much more time, the seemingly fanciful notion of Airbus catching up with and even moving ahead of Boeing in market share acquired reality.

In making airplanes of 150 or more seats, Airbus and Boeing controlled the market. Both had successful product lines. Together they constituted a maturing duopolyan anomaly in this marketplace. Still, nothing stays the same for very long in this business. In just eighteen months, from January 2005 to June 2006, Airbus tumbled off the comfortable plateau it was sharing with Boeing. Its fortunes fell steeply, more so than Boeings had fallen during the decade in which it had lost the leadership role. The top tier of Airbuss management had become nearly as complacent and risk averse as Boeings had been then. Moreover, Boeing had put on offer a new and highly innovative midsize airplane called the 787, one that might all but dislodge Airbus from the richest segment of the market unless Airbus acted swiftly to match its rivals aggressive move. In failing to do that, Airbus is paying, and will continue to pay, a heavy price. That much had become clear by mid-2005.