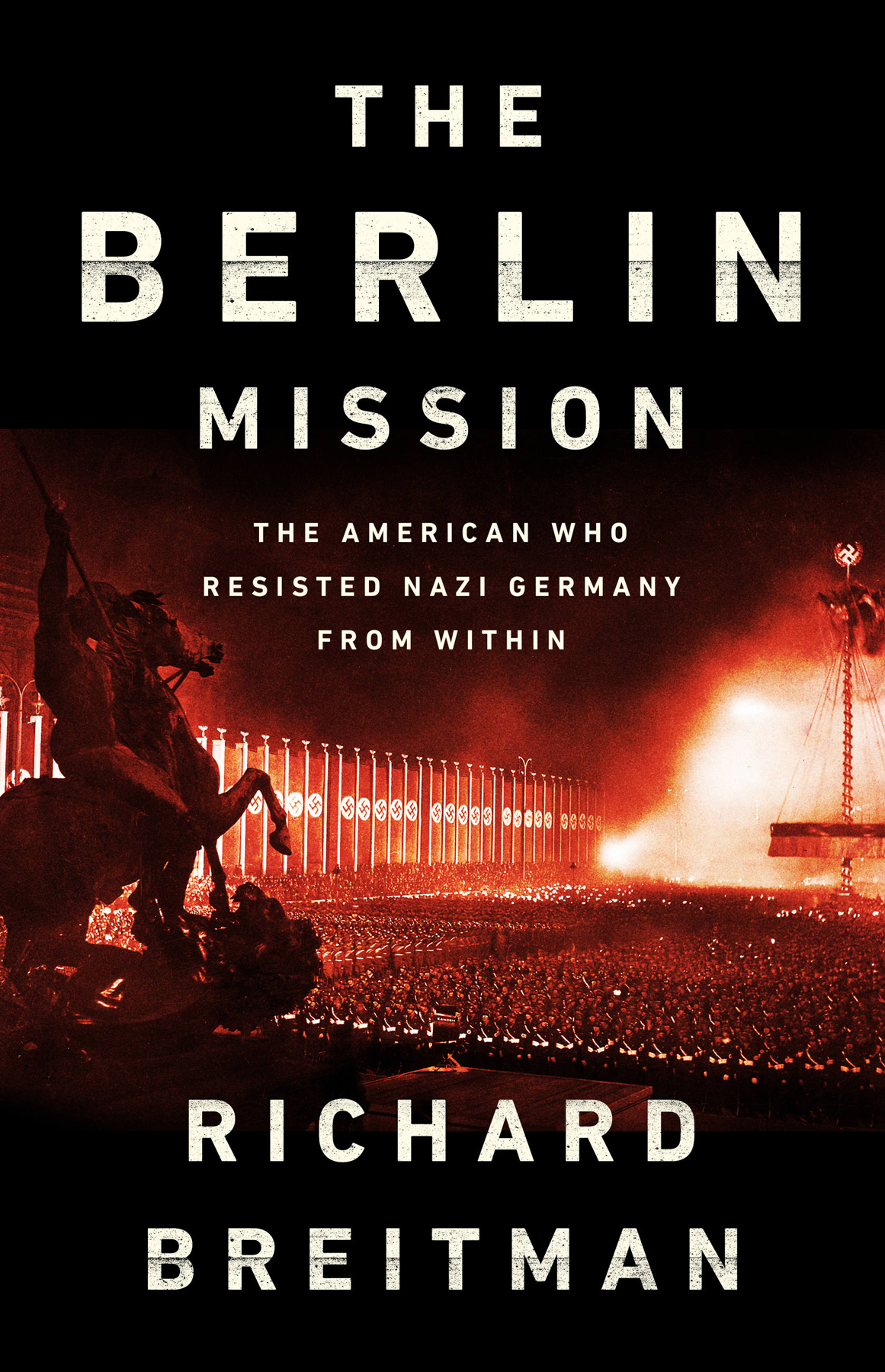

Copyright 2019 by Richard Breitman

Cover design by Pete Garceau

Cover image Sueddeutsche Zeitung Photo / Alamy Stock Photo

Cover copyright 2019 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Letter from Raymond Geist to Hugh Wilson in appendix reproduced courtesy of the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

PublicAffairs

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.publicaffairsbooks.com

@Public_Affairs

First Edition: October 2019

Published by PublicAffairs, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The PublicAffairs name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Breitman, Richard, 1947 author.

Title: The Berlin mission : the American who resisted Nazi Germany from within / Richard Breitman.

Description: First edition. | New York : Public Affairs, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019019036| ISBN 9781541742161 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781541742178 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Geist, Raymond Herman, 1885-1955. | ConsulsUnited StatesBiography. | JewsGermanyHistory1933-1945. | GermanyEmigration and immigration1933-1945. | United StatesForeign relationsGermany. | GermanyForeign relationsUnited States.

Classification: LCC E748.G294 B74 2019 | DDC 943/.004924009043--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019019036

ISBNs: 978-1-5417-4216-1 (hardcover), 978-1-5417-4217-8 (e-book)

E3-20190913-JV-NF-ORI

To Dr. Kenneth Davis, Dr. Myron Schwartz, and Dr. Sean McCance, who made this work possible.

Much of what Hitler did in the German Reich, the processes of dictatorial government which he invented and set in motion, are schemes which any group of politicians might seize upon here or anywhere else at any time! I have seen them worked out to the utmost limit under Hitler; and I fear that we have those among us who would gladly sacrifice their liberties for the kind of precarious security which Hitler provided for his followers for all too brief a time.

FROM A 1940 ADDRESS BY RAYMOND GEIST

O n the evening of January 30, 1939, Adolf Hitler spoke from the podium of the Kroll Opera House in Berlin to the nearly six hundred deputies of the German parliament. High Nazi officials sat on the stage behind him, and on the back wall above was a mounted casting of a huge eagle clutching a large swastika.

About halfway through, Hitler thundered this prophecy: if international finance JewryJews inside and outside Europeonce again plunged the nations into a world war, they would regret it. Gesticulating with his right arm and right index finger, he exclaimed: The result will not be the bolshevization of the earth and thereby the victory of Jewry, but the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe. The Nazi deputies, all of them men, applauded wildly.

Some foreign dignitaries were on hand. Prentiss Gilbert, the senior US diplomat in Germany on that day, had chosen not to attend, fearing embarrassment if Hitler in his speech attacked the United States and President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Gilbert arranged instead to have certain Embassy secretaries get their impressions firsthand.American. He knew exactly what was foreshadowed and he brought this awareness to the heart of his mission: he was our man in Berlin during its darkest decade, and he would do far more than merely bear witness to it.

A young man, five feet ten inches tall with thick, dark-brown hair, intense blue-gray eyes, and a ruddy complexion entered the office of Wilbur J. Carr, director of the US Consular Service on April 21, 1921. This was Raymond Herman Geist, living in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and lecturing at Harvard. He was soon hired as a vice consul, the lowest rung in the Consular Service. His long-shot job interview would later benefit Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, and tens of thousands of German Jews. Few of them ever learned just how he helped them.

During his long stay in Berlin from December 1929 to October 1939, Geist negotiated occasionally with Heinrich Himmler, Reinhard Heydrich, and Hermann Gring. Through his Nazi contacts, he accumulated vital information about the future course of the Nazi regime. His actions influenced not just President Franklin D. Roosevelt, but Adolf Hitler as well. But his unconventional life and work remained buried in obscure files, barely registering with historians.

Geist was a central figure in gathering information about questions that resonate in the twenty-first century. How much did Hitler and other leading Nazis plan their course, and how much did they improvise? What might the West have done to limit or reduce the toll from Nazi persecution and mass murder before war broke out? Was it possible to strike any kind of bargain with Nazi Germany?

Unlike the Swedish activist Raoul Wallenberg, who undertook dangerous rescue activities late in the Holocaust, Geist was a loyal US Foreign Service officer who tried to help Jews and others get out of Germany before the Holocaust. Geist probed the outer limits of what was possible within the system. His aspirations and experiences are still relevant today.

Geists efforts give us a better sense of what was possible in a time of demagoguery, mass murder, and dire threats to Western civilization. His story cautions us against simplistic solutions or partisan distortions retroactively imposed on history long after the events. Indiscriminate moral outrage and scapegoating do not help us learn to deal with our own problems, but the careful study of history might. History does not repeat itself, but sometimes it rhymes.

W hen Raymond Herman Geist came for his fateful interview in 1921, he brought with him a letter of introduction written by an assistant to Herbert Hoover, who had just become secretary of commerce. Geist had worked on the successful presidential campaign of Warren Harding, who had taken office one month earlier, so he had some connections in the capital. But the State Department had no familiarity with his work or credentials.

Geist liked the idea of becoming a diplomat,

Although Geist was lecturing at Harvard, he was a graduate of Oberlin and Western Reserve (now Case Western Reserve), and he had no money to speak of. Maybe for that reason, Wilbur Carr discouraged Geist from a diplomatic position during their interview, but he suggested Geist might manage quite well as a consul.

That would start to change three years later when Carr, among other key State Department officials, arranged the merger of the Consular and Diplomatic Services into a unified Foreign Service. The lines between diplomats and consuls began to blur as consuls were allowed and sometimes encouraged to write economic or political reports to the State Department, and a few crossed over to the diplomatic side. Social distinctions were harder to erase, but the consuls, to the extent they could, began to adopt the style and standards of the diplomats.