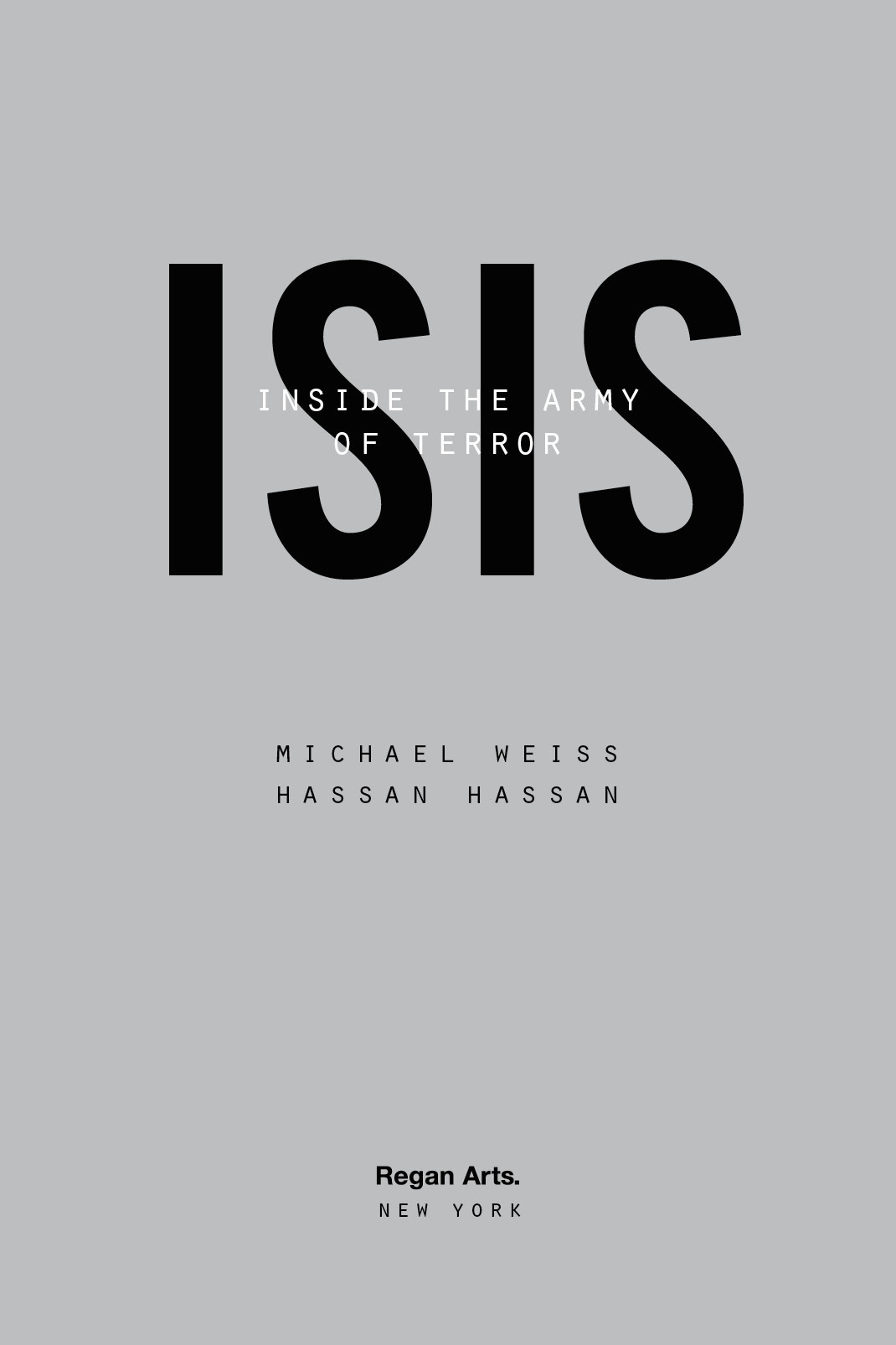

Regan Arts

65 Bleecker Street

New York, NY 10012

Copyright 2015 by Michael Weiss & Hassan Hassan

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Regan Arts Subsidiary Rights Department, 65 Bleecker Street, New York, NY 10012.

First Regan Arts paperback edition, February 2015.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015930621

ISBN 978-1-941393-57-4

Cover art Abaca

CONTENTS

ABU MUSAB AL-ZARQAWIS JIHAD

AL-ZARQAWI AND AL-QAEDA IN IRAQ

BIRTH OF THE ISLAMIC STATE OF IRAQ

IRAN AND AL-QAEDA

IRAQIS TURN ON ISI

ISI AND MALIKI WAIT OUT THE UNITED STATES

SYRIA AND AL-QAEDA

ISI UNDER ABU BAKR AL-BAGHDADI

JIHAD COMES TO SYRIA

PROFILES OF ISIS FIGHTERS

RECRUITING THE NEW MUJAHIDIN

AL-QAEDA SPLITS FROM ISIS

ISIS CO-OPTS THE TRIBES

THE ISLAMIC STATE

For Amy and Ola, who have put up with ISIS (and us) more than any spouses ever ought to

INTRODUCTION

In late 2011, Abdelaziz Kuwan approached his Syrian uncle to connect him to Riad al-Asaad, a colonel in the Syrian Air Force and one of the earliest military defectors from the dictatorship of Bashar al-Assad. Abdelaziz, a sixteen-year-old teenager from Bahrain, wanted to join the armed rebellion in Syria, but his parents forbade him from going. So he defied them.

In early 2012, he flew first to Istanbul and then, as so many other foreign fighters have done, took a thirteen-hour bus ride to the southern Turkish border town of Reyhanli. From there, he crossed into the Syrian province of Aleppo, the northern countryside that had by then completely fallen into the hands of the armed anti-Assad rebellion. Abdelaziz fought for moderate rebel factions for several weeks before deeming them too corrupt and ineffective. Then he migrated through various Islamist brigades, joining first Ahrar al-Sham and then Jabhat al-Nusra, which later revealed itself to be the al-Qaeda franchise in Syria. Having earned a reputation as a fearless and religiously devout fighter, Abdelaziz nonetheless grew disenchanted with his Islamist comrades and faced pressure from his family to return to Bahrain. He did at the end of 2012. Once home, Abdelazizs mother promptly confiscated his passport.

I walk in the streets [of Bahrain] and I feel imprisoned, Abdelaziz told the authors a year later, still pining for his days as a holy warrior. I feel tied up. Its like someone is always watching me. This world means nothing to me. I want to be free. I want to go back. People are giving their lives, thats the honorable life.

Abdelazizs family had moved to Bahrain from eastern Syria in the 1980s. His parents provided him with the means to lead a decent life. His father raised him well, one relative recalled. He did not make him need anyone and wanted him to be of a high social status. The relative added that Abdelaziz was quiet, refined, and always behaved like a man.

Abdelaziz stayed in Bahrain for three months before he managed to persuade his mother to give him back his passport. He left for Syria three days later. Once he arrived, Abdelaziz joined the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS), which was then rising in prominence as one of the most disciplined and well-organized jihadist groups in Syria. Abdelaziz later said that in his last few months in Bahrain he made the decision to join ISIS after speaking with some of the brothers in Syria via Skype. His prior experience with other Islamist factions ideologically similar to ISIS was an advantage in joining one that was dominated by foreign fighters. Abdelaziz rose through the ranks of ISIS, first becoming a coordinator among local emirs and other rebel groups, then delivering messages and oral agreements on behalf of his leader. When ISIS seized enormous swaths of territory in both Syria and Iraq in the summer of 2014, Abdelaziz was promoted to a security official overseeing three towns near the Syrian-Iraqi border town of Albu Kamal, long a portal between the two countries for men like him.

In ISIS, Abdelaziz discovered new things about himself. He learned that he was violent, brutal, and determined. He beheaded enemies. He kept a Yazidi girl in his house as a sabiyya, or sex slave. She was his prize for his participation in battles against the Iraqi Kurdish peshmerga forces and other Kurdish militias in Sinjar, Iraq, near the Syrian border. According to ISISs propaganda magazine, Dabiq , one-fifth of the sex slaves taken from Sinjar was distributed to ISISs central leadership to do with as it so chose; the remainder was divided amongst the rank and file, like Abdelaziz, as the spoils of war.

Abdelaziz showed us a picture of his sabiyya. She was in her late teens. She belonged to Abdelaziz for about a month before she was handed off to other ISIS commanders.

Being a rapist didnt seem to impinge on what Abdelaziz considered his moral obligations as a pious Muslim. One of his fellow warriors said that during news broadcasts Abdelaziz would cover the television screen to avoid seeing the faces of female presenters. He fervently quoted the Quran and hadith, the oral sayings attributed to the Prophet Muhammad, and spoke pompously about al-Dawla , the state, which is the term ISIS uses to refer to its project. Asked what he would do if his father were a member of Jabhat al-Nusra and the two met in battle, Abdelaziz replied promptly: I would kill him. Abu Obeida [one of the companions of the Prophet] killed his father in battle. Anyone who extends his hand to harm al-Dawla will have his hand chopped off. Abdelaziz also called his relatives in the Bahraini army or security forces apostates because his adoptive countrys military was by then involved in a multinational coalition bombing campaign against ISIS led by the United States.

Before he went off to join the jihad in Syria, Abdelaziz had been a theological novice who barely finished a year of Islamic studies at a religious academy in Saudi Arabia. He had dropped out of high school in Bahrain and traveled to the city of Medina to study sharia, Islamic jurisprudence. In school, according to one of his family members, he avoided nondevout peers and mingled primarily with hard-line students. Soon he started to resort to jihadi speak, constantly referring to the dismal conditions in which Sunni Muslims in Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia persist.

In Syria, his metamorphosis continued on the battlefield. He called himself Abu al-Mutasim, after the eighth Abbasid caliph, al-Mutasim Billah, who is known for leading an army to avenge the insulting of a woman by Byzantine soldiers. Abdelaziz said he wanted to emulate the Abbasid caliph in supporting helpless Muslims in Syria and Iraq. Even though he was appointed as a security official, he always looked for any chance to fight on the front lines. I cannot sit down, he told us. I came here seeking martyrdom, and I have chased it everywhere.

On October 23, 2014, Abdelaziz found it. He was shot dead by a Syrian regime sniper in the al-Hawiqa district of Deir Ezzor.

Fighters customarily write a will when they join a group, to be given to their families only after they die. Abdelaziz had addressed his to his mother: As you know and watch on television channels, the infidels, and rafida [a bigoted term used to describe the Shia] have gone too far in their oppression, killing, torture and violations of Muslims honor. I, by God, cannot see my Muslim sisters and brothers being killed, while some of them appeal to Muslims and find nobody coming to their help, and I sit without doing anything. I wanted to be like al-Mutasim Billah. And the most important reason is that I longed for heaven, near the Prophet Muhammed, peace be upon him, and I wanted to ask for forgiveness for you in the afterlife.