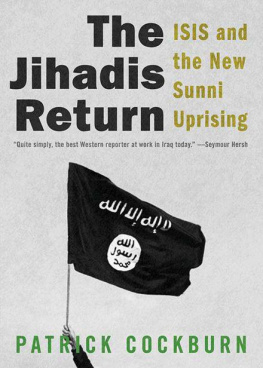

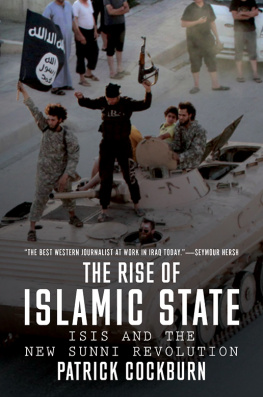

The Rise of

Islamic State

ISIS and the

New Sunni Revolution

Patrick Cockburn

First published under the title The Jihadis Return

by OR Books, New York and London 2014

This updated edition published by Verso 2015

Patrick Cockburn 2014, 2015

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-040-1

eISBN-13: 978-1-78478-049-4 (US)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78478-048-7 (UK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cockburn, Patrick, 1950

The jihadis return : ISIS and the failures of the global war on terror / Patrick Cockburn.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-78478-040-1 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-78478-049-4 (U.S.) ISBN 978-1-78478-048-7 (U.K.)

1. IS (Organization) 2. TerrorismMiddle East. 3. TerrorismReligious aspectsIslam. 4. Middle EastHistory21st century. I. Title.

HV6433.I722C64 2015

956.054dc23

2014041837

Typeset in Fournier by MJ&N Gavan

Printed by in the US by Maple Press

Contents

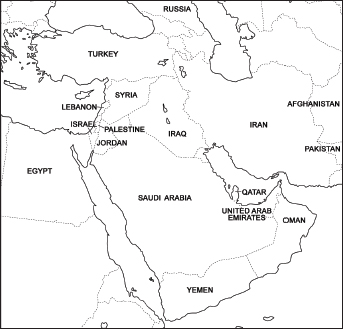

In the summer of 2014, over the course of one hundred days, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS) transformed the politics of the Middle East. Jihadi fighters combined religious fanaticism and military expertise to win spectacular and unexpected victories against Iraqi, Syrian, and Kurdish forces. ISIS came to dominate the Sunni opposition to the governments in Iraq and Syria as it spread everywhere from Iraqs border with Iran to Iraqi Kurdistan and the outskirts of Aleppo, the largest city in Syria. During this rapid rise ISIS acted as though intoxicated by its own triumphs. It did not care about the lengthening list of its enemies, bringing together longtime rivals like the US and Iran by a common fear of the fundamentalists. Saudi Arabia and the Sunni monarchies of the Gulf joined in US air attacks on ISIS in Syria because they felt this group posed a greater threat to their own survival and the political status quo in the Middle East than anything they had seen since Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in 1990.

Iraq and Syria moved closer to disintegration as their diverse communitiesShia, Sunni, Kurds, Alawites, and Christiansfound that they were fighting for their very existence. Merciless in enforcing compliance with its own exclusive and sectarian variant of Islam, ISIS killed or forced to flee all whom it targeted as apostates and polytheists or who were simply against its rule. Its leaders were the products of a decade of war in Iraq and Syria, and deliberate martyrdom through suicide bombing was a central and effective feature of their military tactics. The world had seen nothing like their use of public violence to terrorize their opponents since the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia forty years earlier.

The crucial date was June 10, 2014, when ISIS captured Iraqs northern capital Mosul after four days of fighting. On September 23, the US extended its use of airpower to Syria to prevent the jihadis expansion. During the 105 days separating these two events ISIS rampaged through Iraq and Syria, defeating its enemies with ease even when they were more numerous and better equipped. Unsurprisingly, they attributed their victories to divine intervention.

In contrast, the Iraqi government had an army with 350,000 soldiers on which it had spent $41.6 billion in the three years since 2011. But this force melted away without significant resistance. Discarded uniforms and equipment were found strewn along the roads leading to Kurdistan and safety. Within two weeks those parts of northern and western Iraq outside Kurdish control were in the hands of ISIS. By the end of the month the new state had announced that it was establishing a caliphate reaching deep into Iraq and Syria. Its leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi said it was a state where the Arab and non-Arab, the white man and black man, the easterner and westerner are all brothers Syria is not for the Syrians, and Iraq is not for the Iraqis. The Earth is Allahs.

Al-Baghdadis words showed an intoxication with military victory that only increased as his men outfought and defeated opponents in Syria and Iraqi Kurdistan. The ISIS threat to the Kurdish capital Erbil in August provoked US air strikes inside Iraq, which were later extended to Syria on September 23. US airpower might not have been enough to eliminate or even contain ISIS, but its use forced the fighters to abandon semi-conventional warfare conducted by flying columns of vehicles (often American Humvees captured from the Iraqi army) that were packed with heavily armed fighters. Instead ISIS has reverted to guerrilla warfare, no longer hoping to strike a swift knockout blow against Bashar al-Assad, the Syrian Kurds, or other Syria rebel groups that it had been fighting in an inter-rebel civil war since January 2014.

Over the course of those 100 days, the political geography of Iraq changed before its peoples eyes and there were material signs of this everywhere. Baghdadis cook on propane gas because the electricity supply is so unreliable. Soon there was a chronic shortage of gas cylinders that came from Kirkuk; the road from the north had been cut by ISIS fighters. To hire a truck to come the 200 miles from the Kurdish capital Erbil to Baghdad now cost $10,000 for a single journey, compared to $500 a month earlier. There were ominous signs that Iraqis feared a future filled with violence as weapons and ammunition soared in price. The cost of a bullet for an AK-47 assault rifle quickly tripled to 3,000 Iraqi dinars, or about $2. Kalashnikovs were almost impossible to buy from arms dealers, though pistols could still be obtained at three times the price of the previous week. Suddenly, almost everybody had guns, including even Baghdads paunchy, white-shirted traffic police, who began carrying submachine guns.

Many of the armed men who started appearing in the streets of Baghdad and other Shia cities were Shia militiamen, some from Asaib Ahl al-Haq, a dissident splinter group from the movement of the Shia populist nationalist cleric Muqtada al-Sadr. This organization was controlled by Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki and the Iranians. It was a measure of the collapse of the state security forces and the national army that the government was relying on a sectarian militia to defend the capital. Ironically, up to this moment, one of Malikis few achievements as prime minister had been to face down the Shia militias in 2008, but now he was encouraging them to return to the streets. Soon dead bodies were being dumped at night. They had been stripped of their ID cards but were assumed to be Sunni victims of the militia death squads. Iraq seemed to be slipping over the edge into an abyss in which sectarian massacres and countermassacres might rival those during the sectarian civil war between Sunni and Shia in 20067.