BLACK BANNERS OF ISIS

Published with assistance from the foundation established in

memory of James Wesley Cooper of the Class of 1865,

Yale College.

Copyright 2017 by David J. Wasserstein

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including

illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections

107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for

the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for

educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please

e-mail

(U.K. office).

Set in Janson type by IDS Infotech Ltd., Chandigarh, India.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017931621

ISBN 9780300228359 (cloth : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British

Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992

(Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Colin,

Eshes hayil

Prov. 31:1031

Contents

Preface

T HIS BOOK BEGAN AS an attempt to clarify a superficially simple set of questions. What kind of Islamic state is the Islamic State (IS)? Is IS simply another terrorist outfit, splintering from al-Qaida, or should we see in it something different, something new, something with the potential to set off changes of world-historical significance? That is what the founder of IS Abu Musab al-Zarqawi means when he writes, The spark has been lit here in Iraq, and its heat will continue to intensifyby Allahs permissionuntil it burns the crusader armies in Dabiq. How, other than in terms merely of terrorism in the Internet age, should we understand IS, and how should we think about reactions to it? How should the presence of IS affect Western, non-Islamic ways of relating to Islam and Muslims?

In the process of looking for answers to those questions, naturally I have found others and unearthed old debates about what it means to be Muslim and Islamic, as well as what it means to look at a religion, a culture, a civilization from the outside. The erudition and learning of the late Shahab Ahmeds recent publication What Is Islam? The Importance of Being Islamic did much to stimulate concern and illuminate what we Westerners do not yet know. But inevitably, especially given when the author was working on it, that book could not offer direct answers to questions specifically about IS. Other works, by journalists and scholars in particular, often seemed not to go deeply enough into the historical background of the issues involved, in part because of a perfectly understandable concern with day-to-day developments in the Middle East and elsewhere. The cost, perhaps inevitable, of that is a paring down of a concern with the non-immediate, the past.

My concern, by contrast, is with the past in the present, the present in its past. That past has two separate, if interlinked, elements. One is Western involvement with the world of Islam, an involvement that stretches from the beginnings of Islam to ongoing adventures in Afghanistan and Iraq. The term crusader, deployed to great effect by IS and others as a label for Westerners, some of whom are Christians, reduces our understanding of that involvement to one of hostility and destructiveness, mutual ignorance and irreconcilable faith claims, power relations and intolerance and suspicion. The truth is that the connection has been far more complicated and messyinteresting, exciting, and rich, in both positive and negative waysever since the birth of Islam.

The other element is the larger Islamic past that feeds and forms IS as it does numerous other movements, ideologies, and cultures within the penumbra of Islam as a whole. In this book I have tried to look at IS as a phenomenon of the world of Islam, not in terms of alleged influences coming from outside or as a product of Western policies gone wrong. At least as a first step, it makes sense to look at such a movement as IS on its own terms, and those are at base those of the world of Islam.

My subject is a moving target. I have tried to keep up-to-date with events in the process of researching and writing this book, but inevitably, important changes and developments will have occurred between my writing of these lines and their appearance in print. As I write this IS is losing ground militarily, but the pendulum is likely to move to and fro for some time before IS is forgotten.

I have learned much in preparing this book. As a student of medieval Islam I have learned that the dead speak, and that the living listen. As a non-Muslim I have learned to see Islam as a living, changing faith in the world, and its faithful as members of a vital tradition with many mansions. Above all, in writing about IS, I have tried to lose the bogeyman approach thrust upon us by so many of our leaders and guides and to see through the veil to the reality within.

Along the way I have been fortunate to benefit from advice, help, and encouragement from a wide variety of sources. During the academic year 20152016, together with two Vanderbilt colleagues, I led an Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Sawyer Seminar on the subject When the Fringe Dwarfs the Center: Vernacular Islam beyond the Arab World. It is a pleasure to thank the Mellon Foundation for its support of our endeavor; the Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities at Vanderbilt, which hosted us for the year; its director and staff; and in particular fellow members of the group and our guests for an enriching year that contributed enormously to shaping how I think about Islam in its non-Arab forms and how I write about Islam.

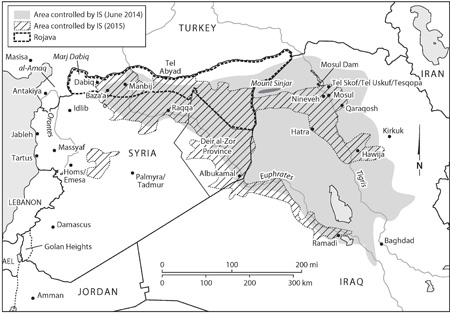

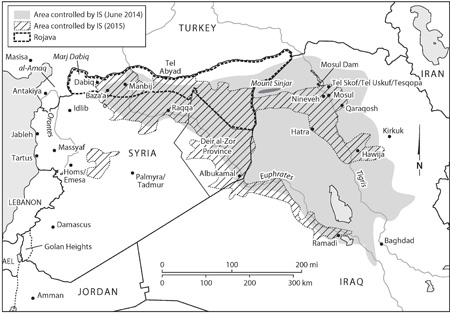

At Yale University Press, I have been fortunate in my editor, Jennifer Banks, who encouraged this project from the beginning. Her assistant editor, Heather Gold, shepherded me through the publication process. Julie Carlson, my copy editor, tolerated the transatlanticisms of a transplanted author. I am particularly grateful to Bill Nelson, of billnelsonmaps, for the map that graces this volume.

I presented versions of my thinking on this topic to the Vanderbilt History Seminar in January 2016, and subsequently to two other seminars. My thanks go to my hosts on those occasions and especially to those friends, colleagues, studentsmy teachers allwho attended and took part in the discussions following my talks. Family, friends, colleagues, and even total strangers on three continents and in the United Kingdom, Muslims and non-Muslims alike, have been unfailingly and instantly responsive to a stream of letters and calls demanding urgent assistance. I hope that they will accept this general expression of a gratitude that is deep in inverse proportion to the brevity of its expression. On such a subject as this, an unwonted anonymity appears preferable to an unwanted notoriety. Anonymity, however, gives way to notoriety in the greatest debt of all. That is expressed in the dedication to this book.

BLACK BANNERS OF ISIS

Map of Areas under Islamic

State Control

Introduction

The Islamic State

W E KNOW BOTH TOO much and too little about the Islamic State. The strategic use of violence and terror by IS, together with its ability to conquerand, so far, retainhuge swaths of territory including major cities and frighteningly large populations in Iraq and Syria, have moved it, with tremendous speed, from the margins to the center of what is happening in the Middle East. Selfless individual bravery and skilled tactical maneuvering in the field by IS fighters, as well as a willingness by IS to sustain the losses required for multifront operations against the militaries of Iraq and Syria, and other non-state actors in these two countries, show that IS is not just going to fade away. Support from Iran and the United States and their allies does little to help Iraq and Syria. Western media accounts of knock-out blows against individual IS leaders, or seizures of computers and financial records, are being countered with reports of new victories and further conquests.

Next page