The Santiago Campaign, JuneJuly 1898

Erin Greb Cartography

INTRODUCTION

NEW YORK CITY, 1899

I t was the grandest parade New York City had ever seen. It began with the ships243 of them, battleships, cruisers, torpedo boats, armored yachts, practically every ship in the American Navy, alongside dozens of private craft, carrying 150,000 sailors and passengers, gathered in the early evening of September 29, 1899, off the eastern coast of Staten Island, to celebrate the American victory in the Spanish-American War a year before. As fireworks ripped into the sky from scores of sites around New York Harbor, the fleet sailed forth, cruising through the Narrows between Brooklyn and Staten Island. Under the glare of red, white, and blue starbursts, three and a half million peopletwo and a half million New Yorkers and another million visitors, who came from as far as Californiawatched along the harbor shorelines. To accompany the fireworks, the fleet beamed hundreds of spotlights on the crowds and buildings along the waterfront. Wherever the eye turned, it was blinded by the magic light... and all the cities seemed to be bathed in harmless fire, wrote one observer. For two hours this went on, and there was more to come: The next day 30,000 soldiers, led by a 130-piece band conducted by John Philip Sousa, marched from Morningside Heights to Madison Square, in Manhattan, where artisans had erected a triumphal arch of lath and plaster, modeled on the Arch of Titus in Rome.

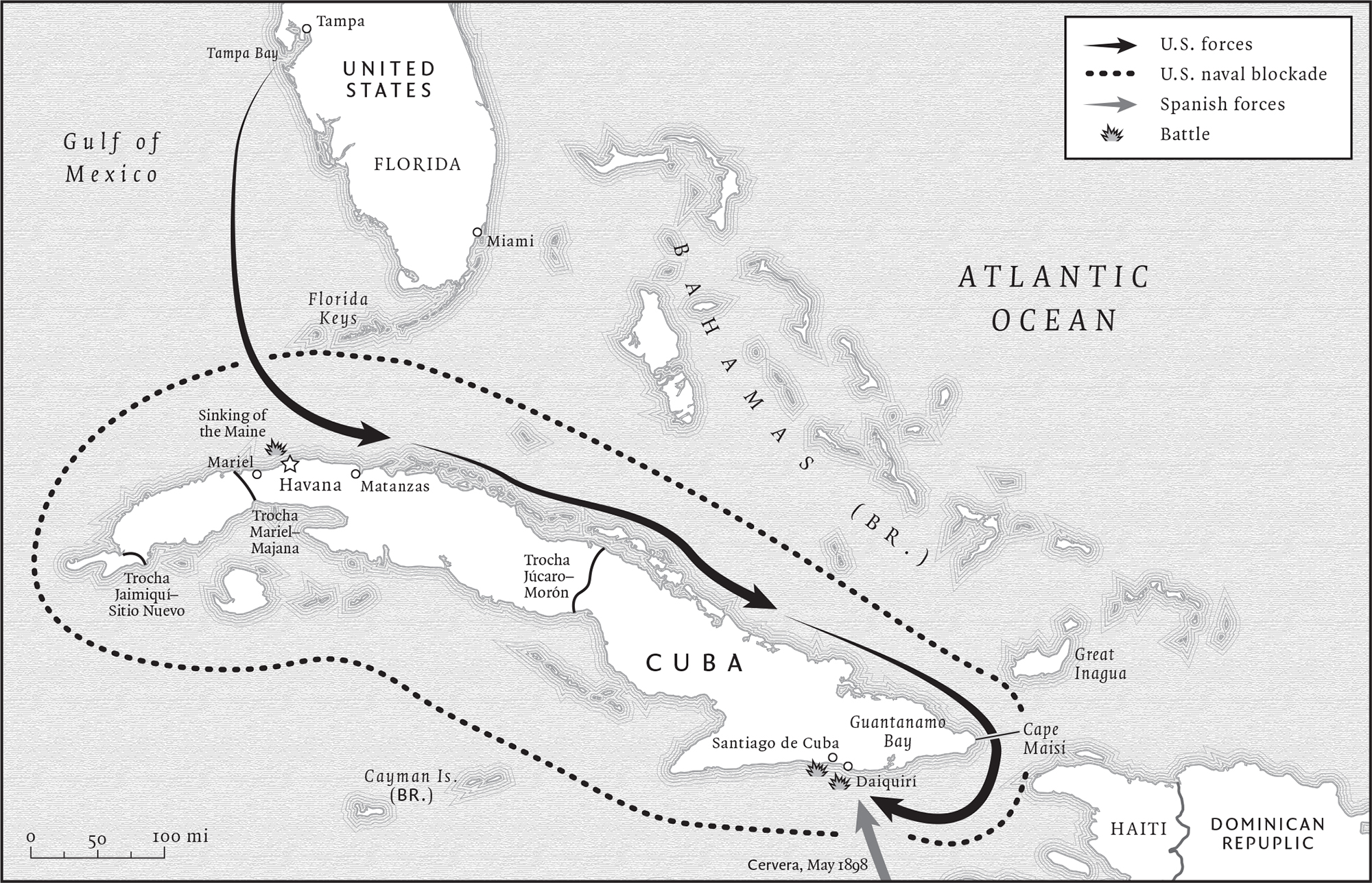

In just a few months in 1898, the United States had defeated Spain and captured Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines; in a separate move, it had annexed the Hawaiian islands. The United States and Spain had signed a peace treaty at the end of the year, but it took nine more months to coordinate a celebration with so many men, and so many ships, some deployed halfway around the world, to meet in

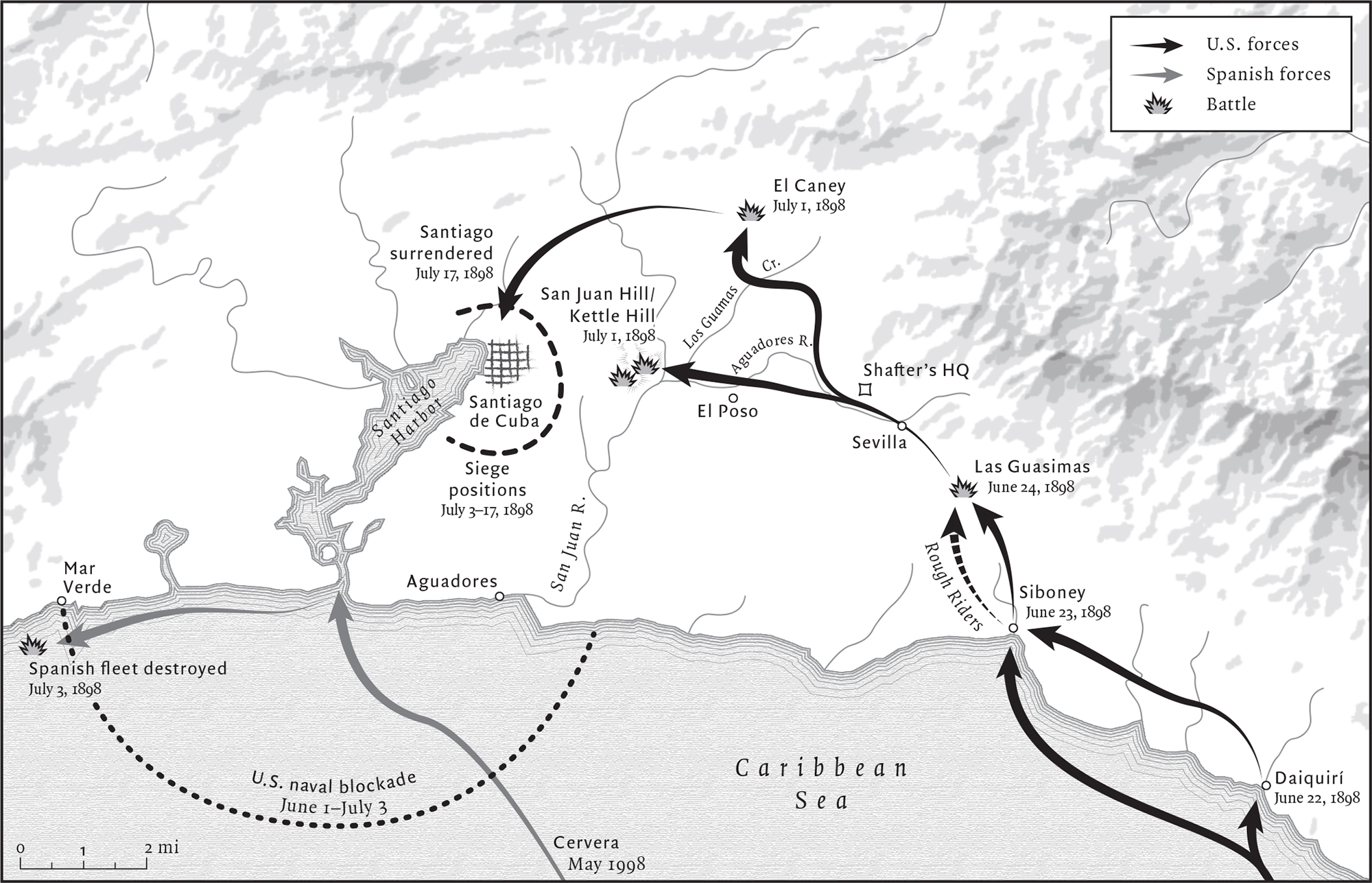

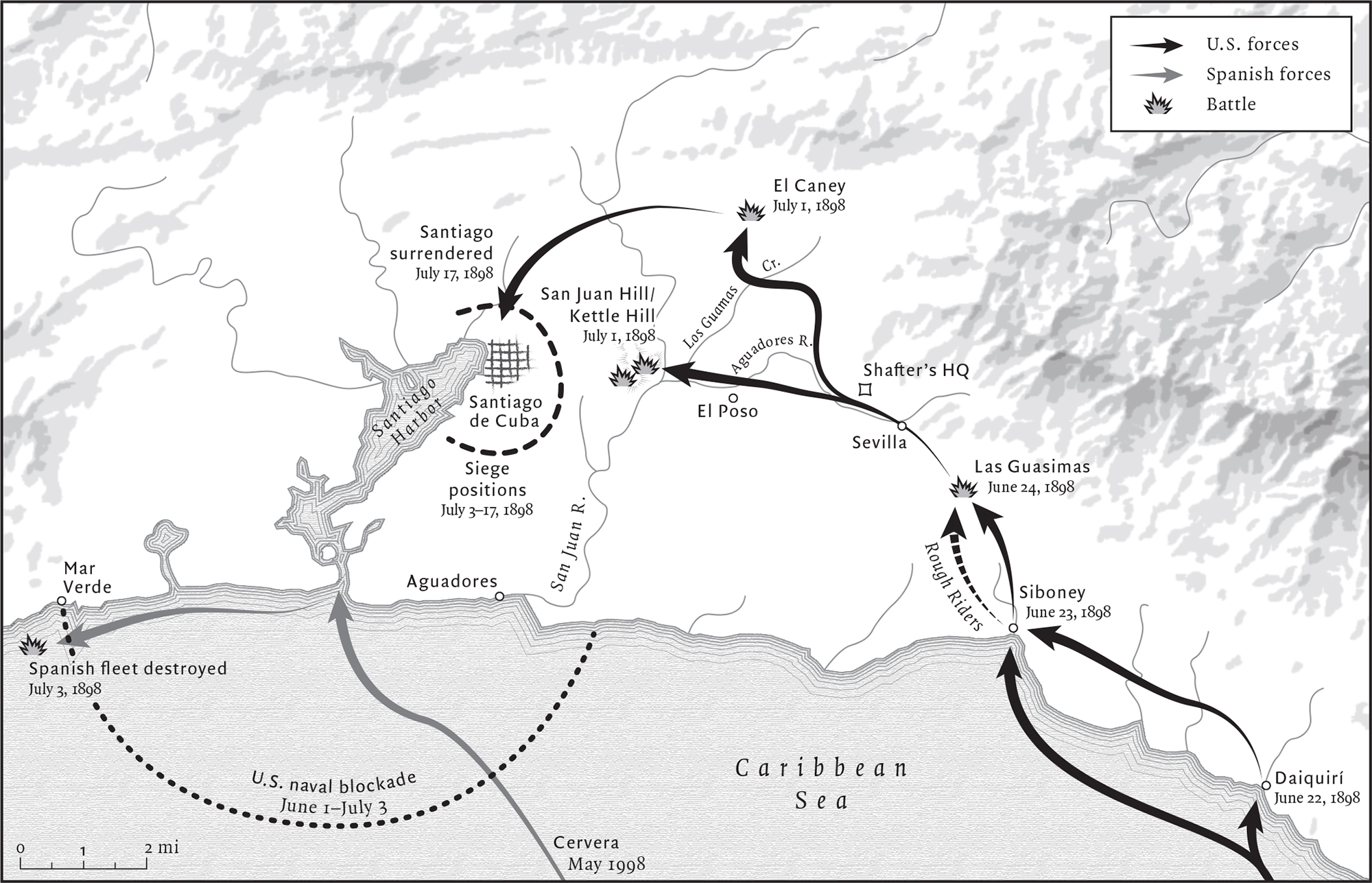

Riding that day at the head of the New York State National Guard as it marched along the parade route was Theodore Rooseveltnaturalist, historian, war hero, and now governor of New York. Dressed in a frock coat, top hat, and kid gloves, he was the most powerful politician of this mighty state and a scion of the citys patrician class. But he was more than that: Perhaps no single person better embodied the excitement and national pride the war elicited, and the newfound martial fervor that followed. At the outbreak of the Spanish-American War, he had resigned from his job with the Department of the Navy to help lead the First United States Volunteer Cavalrybetter known as the Rough Ridersduring the invasion of Cuba. Roosevelt had trained the regiment, one of twenty-six in the invasion force and totaling nearly 1,000 men, then led them to Cuba and into battle, culminating in a desperate, riotous charge up a hill outside the city of Santiago, on the islands southeastern coast. He returned victorious and world-famous, an American Caesar who took Albany a few months after taking Santiago and now, everyone said, was poised to take the presidency, too. Though the parades official man of honor was Admiral of the Navy George Dewey, who had defeated the Spanish Pacific fleet at Manila at the outbreak of the war, it was Roosevelt whom many in the crowd wanted to see that day. Halfway through the march, at 72nd Street, he paused to tip his hat to a reviewing stand. The crowd exploded, shouting Teddy! Teddy! and Roosevelt for president! Onlookers, trying to get close, pushed into the street; police had to hold them back. Aside from Dewey, the Times wrote, the interest and admiration of the thronging people were expressed more uniformly and enthusiastically toward Governor Roosevelt than toward any one else.

Roosevelts experience as a wartime leader raised his national profile and changed him utterly. Until then, his career had included politics, ranching, history writing, and biology; he was good at most of

Instead, he blossomed as a leader. He trained and led his men into battle, then watched over them during a grueling three-week siege outside Santiago, in which the bigger enemies, more so than the Spanish, were heat, disease, rats, and rainstorms. He kept his men in line, and he kept them loyalyears later, when Roosevelt was president, groups of Rough Riders would stop by the White House for a visit, and they were always allowed to skip past the crowd outside his office. It was these skills, as much as his charisma and unending appetite for work, that made Roosevelt such an effective public executiveas governor and, in 1901, as president.

Roosevelt blossomed intellectually as well. The experience with the Rough Riders, and his time at war, helped him hone his ideas about America, its place in the world, and his philosophy of the strenuous life that governed his approach to the presidency. It helped him clarify his complicated and flawed ideas about American unityhe embraced the notion of a country brought together by common values and a mission to bring those values to the world, even as he endorsed its exclusion of a large swath of its population behind disenfranchisement and Jim Crow. Roosevelts time in Cuba also brought home for him the importance of what his generation called the manly virtuesthe social Darwinian notions of competition, often violent, between men, and between nations. He did not discover these ideas on the battlefield, but the battlefield offered all the evidence he needed of their veracity, as well as the prestige to spread them among his adoring public. He became, wrote the historian Gail Bederman, a walking advertisement for the imperialistic manhood he desired for the American race.