Table of Contents

Also by Michael A. Bellesiles

Arming America: The Origins of a National Gun Culture

Documenting American Violence: A Sourcebook

(co-edited with Christopher Waldrep)

Ethan Allen and His Kin: Correspondence, 1772-1819

(co-edited with John Duffy)

Lethal Imagination: Violence and Brutality in American History (editor)

Revolutionary Outlaws: Ethan Allen and the Struggle for Independence on the Early American Frontier

A Survival Guide for Teaching

Weighed in an Even Balance

For Nina

What is essential is invisible to the eye.

Acknowledgments

In times of great grief, we learn anew the value and extent of friendship. There are those who cannot bear to witness pain and understandably step quietly away, while others display such kindness and personal loyalty as to lighten the burden of loss. I have been fortunate to have far too many of the latter to thank each in turn, but I would be sorely remiss if I did not express my profound debt of gratitude to a few people who have rendered aid in a time of need. I can never thank Kathy Hermes enough for getting me back into the classroom where I belong. But more than that, her courage in standing up to bullies has been an inspiration and a valuable reminder of why teaching and writing are so important. Stephen Wasserstein, my boss at Cengage Learning, has become a valued friend who keeps me grounded in both the needs of readers and the merit of clear prose. From death row, Eric Wrinkles remained a rock of friendship, patient and understanding until the moment he was put to death. Forever upbeat and positive, Carol Berkin evokes awe; her brilliance and boldness are matched only by her loyalty as a friend. I owe Carol a special debt for introducing me to her agent, and now mine, Dan Greenit is hard to imagine a finer agent. I have learned to rely on his wise counsel and blunt honesty; it has been a rare pleasure working with such an insightful critic. His connecting me with The New Press and my editor Marc Favreau was particularly fortuitous; their integrity and forthright nature have made writing this book a pleasure. My thanks as well to Sarah Fan and Cathy Dexter, whose editorial work improved this work considerably. I hope that all my other friends realize how much their time, patience, and continuing support have meant to me. I look forward to thanking you each in person.

Immersing oneself in a single year as I have done with 1877 can lead to a feeling of fellowship; at times it seems as though I know many of these people personally. The appalling villains are matched by the many admirable and courageous people who fought for their beliefs in a troubled time. In letters, journals, memoirs, and the decaying newspapers from the past, I also came to know a number of people who insisted on living joyous lives despite the darkness around them. As an historian, it is my task to do these people justice, to treat them with respect and let them speak for themselves. I hope that I have succeeded in attaining these goals. Similarly, one of the pleasures of research is rereading favorite bookssuch as those by Henry May, Kevin Kenny, and Elliot Gornand discovering new authors like Rebecca Edwards, Susan Jacoby, and Edward Blum, who bring history to life. I trust that my debt to other historians is abundantly clear in the pages of this book; their scholarship and intelligence have served as my guide.

Ultimately, the contents of a book are the responsibility solely of the author, and I embrace that burden. However, I could not have taken on this task without the support of my family. My father, Jacques, my siblings, Matt, Mark, Kathleen, and Lisa, and my patron saint Raymond have kept the faith and seen me through. My daughter, Lilith, becomes ever more brilliant while remaining gracious and loving. My wife, Nina K. Martin, to whom this book is dedicated, has had to live with my obsession with 1877, and has done so with good humor. Her love, loyalty, and honesty sustain me; her intelligence inspires me; and her appreciation for my cooking reminds me what matters most in life, the joyful company of loved ones.

Preface

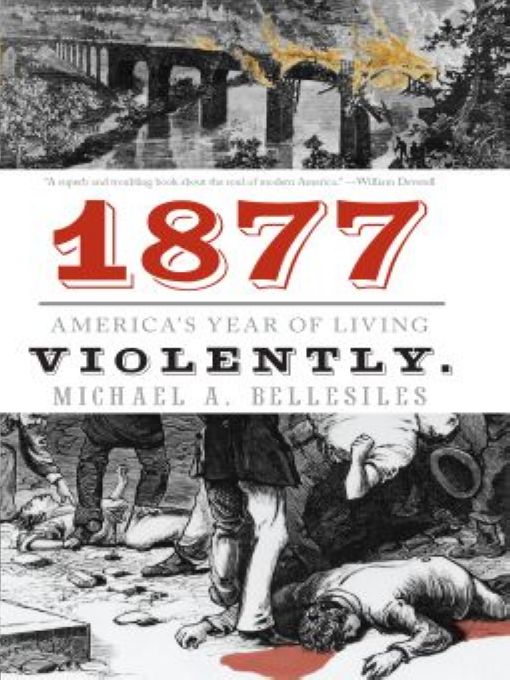

The year 1877 may rank as one of the blackest in the nations annals.

Allan Nevins

As Carl Sandburg observed, the Civil War had been fought over a verb: does one say the United States is or the United States are? In 1865 the matter seemed settled in favor of the former. At the expense of more than six hundred thousand lives, the idea of national unity based on the principle of freedom had apparently triumphed. But just a dozen years later that certainty was fading fast as angry and committed Americans pulled the country in divergent directions. In the South, white racists rose again in an attempt to seize power through violence and intimidation, seeking to negate the newly won rights of one-third of the regions inhabitants. Out on the Great Plains, the U. S. Army suffered repeated defeat at the hands of migratory Indians, while in Texas public officials from the governor on down issued panicked calls for federal troops in the face of a Mexican invasion that threatened a new war. In the far West, white demagogues linked the rights of labor with racism, calling for both labor unions and war against Hispanics and Asians. Meanwhile the entire country was in the grip of the centurys worst depression while the specter of communism and aggressive labor agitation threatened to topple the very foundations of the capitalist order. Around the country Americans killed one another in record numbers previously seen only in time of war. And to top it all off, it looked as though the country would not have a president by inauguration day, March 4, 1877. As the historian Henry May wrote, The year 1877 remained a symbol of shock, of the possible crumbling of society.

This book examines one of the most tumultuous years in American history, arguably the most violent year in which the United States was not in the midst of war. Some years in a specific country take on an identity of their own, such as 1848 in much of Europe or 1968 in the United States, with every aspect of society and culture facing challenges and teetering on the verge of transformation. The year itself has no character of its own, of course, but contemporaries attach value to the calendar and frame events through the personality they impart to their time. The centennial year of 1876 was supposed to have been significant for the United States, yet most observers felt like the country had just been holding its breath. Despite the many parties and celebrations, the country was in the midst of a terrible depression, with business failures and unemployment reaching new heights. But 1877 was different. With the party over, the guests seemed intent on trashing the house.

For contemporaries, 1877 was a year unlike any other, and it continued to haunt their memories. From the day the year started, with news of the Ashtabula rail disaster, through its end and threats of a communist rebellion, it seemed that everything that could go wrong did.

It did indeed seem as though the whole country had suddenly changed direction. Since at least the Missouri Compromise of 1820, the nation had pivoted around race and slavery. Now, twelve years after the end of the destructive but liberating Civil War, racial relations gave way to class conflict as the primary political and social issue facing the United States. That is not to say that race was no longer important, but rather that the majority just did not want to talk about it anymore. Clearly many white Americans were frightened by the world they had created and hoped to turn back the clock to a less threatening time, as the democratic expansion of Reconstruction unleashed dangerous impulses. In 1877 a white woman in Alabama named Julia Green was jailed for two years for marrying a black man. For the next fifty years, the consequences of industrialism would dominate the national discourse, while the rights of African Americans would be largely forgotten.