ABOUT THE AUTHOR

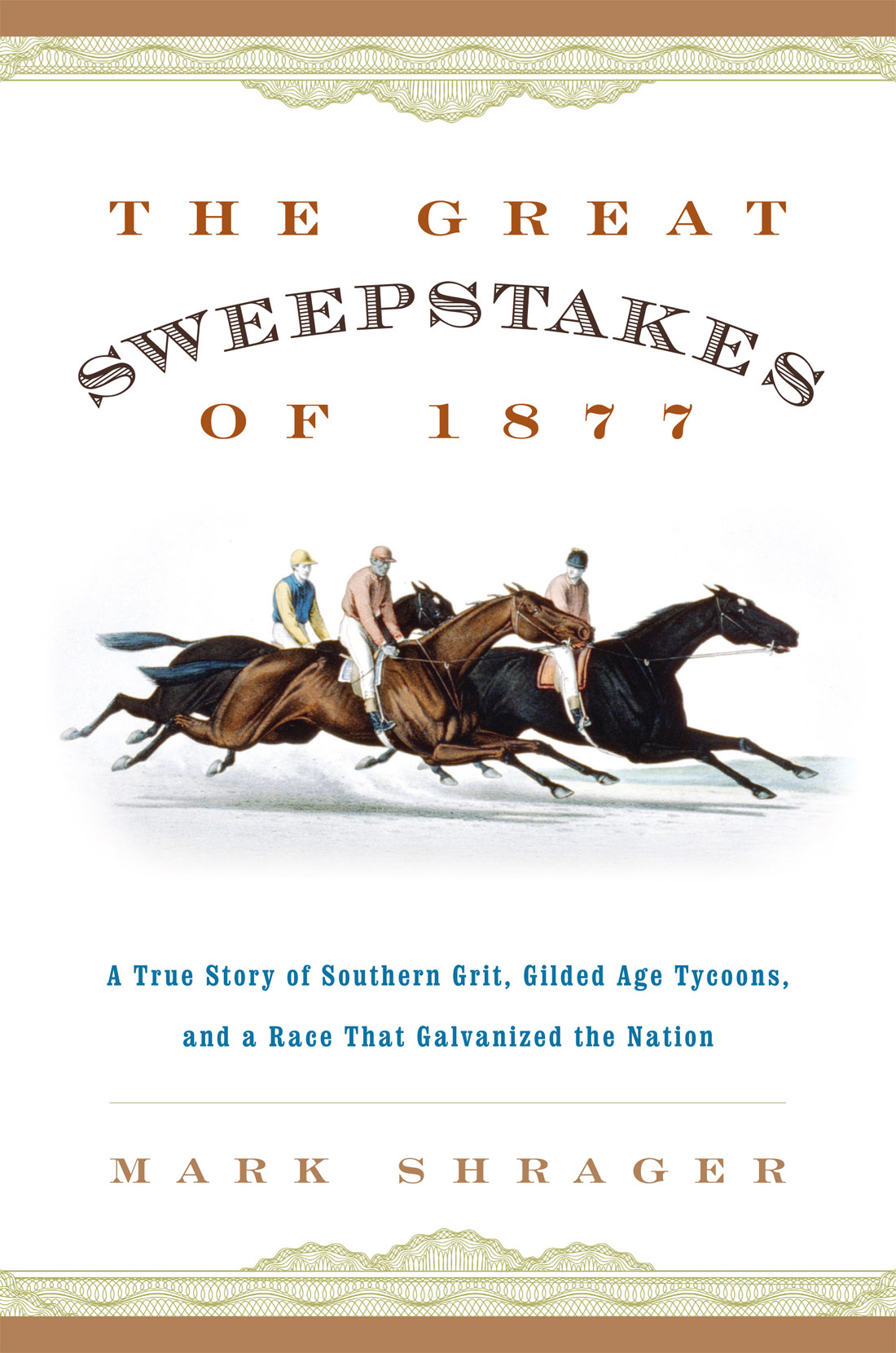

Mark Shrager is a prolific turf writer, having published several hundred articles in magazines such as Turf & Sport Digest , American Turf Magazine ( ATM ), and others. His article 1,001 Surefire Ways to Lose a Horse Race was published in the annual Best Sports Stories anthology. Shrager has also published two books of Breeders Cup handicapping information. Six years of research, including stretches in Kentucky and at the Library of Congress, have led to The Great Sweepstakes of 1877 . He lives in Altadena, California.

An imprint of Rowman & Littlefield

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2016 Mark Shrager

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

ISBN 978-1-4930-1888-8 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-1-4930-1889-5 (e-book)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

PREFACE

A SLOW DAY IN CONGRESS

October 24, 1877, was a day of minimal activity in the halls of Congress. The US Senate was not in session, having adjourned the previous day and calendared no activity until the twenty-fifth; the House of Representatives was largely empty, and in any event was scheduled to address only a few items, primarily a variety of petitions and claims remaining from the Civil War, which had concluded some twelve years earlier.

That small group of Congressmenand they were all men; Congress had broken the color barrier in 1870 with the seating of Senator Hiram Rhodes Revels of Mississippi and House Member Joseph Rainey of South Carolina, but it would be nearly forty years before Montanas Jeannette Rankin would become the first female member of Congressconsidered the petitions and motions dispiritedly. With so few members in attendance, Congress would accomplish nothing of note on October 24. One can readily imagine the few remaining legislators voices echoing eerily in the cavernous, nearly empty halls of the House of Representatives.

The handful of legislators in Congress on October 24 was well aware of the reason so few were present for the days session. Some may have glanced resentfully at the empty desks of their absent colleagues, but most participated resignedly, performing the work of the nation as they had been selected to do. Finally, at 3:25 p.m., the Honorable Fernando Wood, perhaps best known as the Civil War mayor of New York who had suggested that his city secede from the Union rather than sacrifice its profitable business relationship with the Confederacy, rose to move that the House adjourn. Upon passage of the motion, Congress called a merciful end to its unproductive day.

While October 24, 1877, represented something less than a shining example of the US Congress at its finest, the date nevertheless earned a unique place in history. It was on this date that the nations senators and nearly all representatives abandoned the halls of Congress to attend an occasion of less repute but considerably more sporting interesta specially arranged and long-anticipated horse race at nearby Pimlico Racetrack involving three of the nations best-known thoroughbreds. It marked the first time in the nations history that either house of Americas most august legislative body had adjourned specifically so that its members could attend a horse race.

It was a race of enormous national interest, both to elected officials and to Americas common folk. The race involved two high-profile Eastern thoroughbreds, Parole and Tom Ochiltree, one hailing from the New Jersey headquarters of one of the nations preeminent sportsmen and industrialists, the other from the New York stable of his brother.

The third starter was Ten Broeck, an invader from the West, in this case the state of Kentucky, whose unrivaled record on the turf had already made him legendary in his own time. The opportunity to partake of this East vs. West rivalry, and perhaps extract a profit through a few well-placed wagers, proved far more enticing to many of the legislators than the essential but less exciting business of Congress.

Although East and West were the compass points discussed in the days newspapers, and in polite conversation in Congress and on the street, many would have recognized that the race also symbolized the North vs. South hostilities that had so recently and profoundly shaped the nations racial relations, its family structures, its international relations, and its domestic politics. New York and New Jersey had, of course, been squarely pro-Union during the Civil War, even given the draft riots that had shattered the peace of the Empire State, even given the sentiments of Mayor Wood. Kentucky had been a slave state whose legislators had declared it a neutral party, doubtless in the hopes of doing business with both sides, Union and Rebel.

The Civil War had been the deadliest conflict in American history. It had long been estimated that the War Between the States cost the lives of at least 625,000 combatants360,222 on the Union side and roughly 258,000 Confederatesbut recent scholarly recounting of census records suggests that the toll may have been substantially higherperhaps upwards of 850,000. More soldiers on both sides died of non-battle causesprimarily disease and hungerthan of gunshots, bayonet strikes, or other human violence. Multiples of these numbers were left permanently debilitated.

More than 150 years after the wars end, after two World Wars, after Korea and Vietnam, after two Gulf Wars and a protracted American presence in the Middle East, the Civil War remains the deadliest conflict in the history of a nation that has, by dint of its economic and military might, been among the combatants in many an armed struggle. Owing to the slow communications of the times, overt hostilities between North and South continued even after the war was diplomatically concluded; the final Confederate general to surrender was Cherokee leader Stand Watie, who conceded defeat at Doaksville in the Choctaw Nation (now Oklahoma) on June 23, 1865, some two and a half months after Lee laid down his sword.

The regional rivalries that had existed long before the Civil War had been nurtured in the years that followed the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. The surrender of Robert E. Lee at Appomattox Court House had formally ended the war, but while most of the conflagrations nonfatal physical wounds were slowly healing, Americas emotional scars remained and, in some cases, festered. The disputed presidential election of 1876, pitting Republican Rutherford B. Hayes against Democrat Samuel J. Tilden and decided by a single electoral vote after four states electoral slates were claimed by both political parties, exacerbated tensions that were already near the breaking point.

It is no exaggeration to suggest that Hayess hairsbreadth victory in the Electoral College, awarded to the Republican candidate despite Tildens sizable margin in the popular vote, brought the nation to the brink of a second Civil War. When an election commission, established by Congress to sort out the votes in the four disputed states, awarded each of the states to Hayes by a strictly partisan eight-to-seven votethe commission comprised eight Republicans and seven DemocratsCongressional Democrats threatened a filibuster to delay Hayess inauguration. It is questionable whether an elected president could be denied his office because of a political maneuver in Congress, but the possibility was there. More ominously, one frustrated Democrat vowed that a hundred thousand Kentuckians would see justice done to Tilden and the Republicans reportedly considered using the army to enforce the election commissions rulings. Only when cooler heads prevailed, creating the Compromise of 1877, was what historian James Truslow Adams described as the filthy mess of 1876 brought to a conclusion.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.