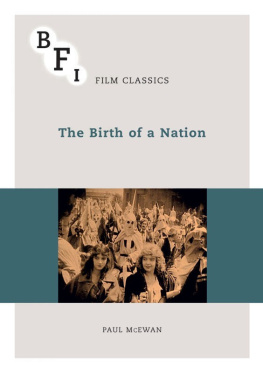

THE BIRTH OF A NATION

Copyright 2014 by Dick Lehr

Published in the United States by PublicAffairs, a Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address PublicAffairs, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

PublicAffairs books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

Book design by Trish Wilkinson

Set in 10.25 point New Century Schoolbook

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lehr, Dick.

The Birth of a Nation : how a legendary filmmaker and a crusading editor reignited Americas Civil War / Dick Lehr. First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

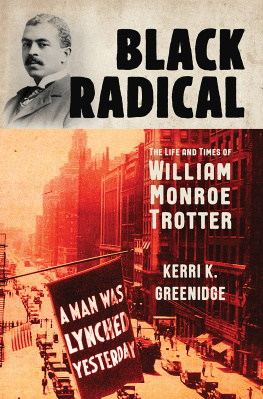

ISBN 978-1-58648-988-5 (e-book) 1. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Motion pictures and the war. 2. Birth of a nation (Motion picture) 3. Griffith, D. W. (David Wark), 18751948. 4. Trotter, William Monroe, 1872-1934. 5. United StatesRace relationsHistory20th century. I. Title.

E656.L44 2014

305.800973dc23

2014029679

First Edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my daughters, Holly and Dana

CONTENTS

T his is a work of nonfiction. The people are real; no names have been changed; no changes have been made in the chronology of events. Dialogue is based on letters, journals, newspaper reports, and other archival records. Regarding terminology, I made the decision to use the terms Negro and colored that were commonplace during the period when this story occurredthe early twentieth century. When I read narrative histories I find the use of present terms African American or black jarring; they take me out of the historical moment. Besides, terminology is fluid. For example, the journalist Ray Stannard Baker, in a 1908 article titled An Ostracised Race in Ferment, made this observation: Many Negroes who a few years ago called themselves Afro-American or Colored Americans and who winced at the name Negro now use Negro as the race name with pride. It is also worth noting that the Associated Press, long the arbiter of style in journalism, in December 1914 issued this comment about usage: We have a broad rule to the effect that the word Negro should be capitalized in our service, but we do not control the typological appearances of the word as it appears in the newspapers. The latter part of the comment was the APs way of dealing with the fact that many newspapers using its service either changed Negro from upper to lower case or substituted derogatory terms in its place. Finally, Monroe Trotters preferred term changed over time; early on he favored Negro, but he later came to think that term suggested separatism and so he switched to Colored or Colored Americans.

January 2, 1915

D avid Wark Griffith watched intently as curious residents of Riverside, California, filed into the Loring Opera House for a Saturday evening preview of a new movie promoted as the Most Wonderful Motion Picture Ever. The moviegoers crowded the ornate thousand-seat theater, which first opened in 1890 to showcase opera and musicals and had only just begun to present the new medium of film.

Excitement was building. Griffith, the motion pictures director, had personally arranged the eight p.m. screening. He had even persuaded many of the films stars to attend the sneak preview: among them the enchanting Lillian Gish, doe-eyed Mae Marsh, and popular leading man Henry B. Walthall. The director had wanted to get away from the hubbub of his Hollywood studio, choosing this young city sixty miles inland from the expansive, big-sky locations in the California hills where hed filmed some of the movies panoramic battle sequences.

As was his custom for test screenings, Griffith settled into a seat at the back of the theater, not far from the booth where projectors were hand cranked. The operator had to find a frames-per-second speed that would satisfy Griffith: The pace had to suit both the fury of galloping horses and the solemnity of a death scene. His secretary and film editorthen called a film cutterby his side, Griffith was at once studying the film and gauging the audiences reaction, dictating notes for additional edits. Every single subtitle, every situation, every shift in scene or change in a sequence that is made in editing a film, has to go before an audience for its test before being accepted as part of the complete product, the director said about his process. Griffith was fanatical about his finishing touches. He was preparing for the premier in Los Angeles the next month, with even bigger things to come afterward, including a trip to Washington DC, to show the movie to President Wilson in what would be the first-ever film screening inside the White House.

The Kentucky-born director was to celebrate his fortieth birthday in three weeks, but the personal milestone paled in comparison to the impact his film was going to have on the history of American cinema. For Griffith, 1915 marked the culmination of a professional journey that had begun in earnest at the turn of the century with his arrival in New York City as a raw, aspiring actor. He turned to directing in 1908, but nothing hed made so far came close to the production quality of his new movie that took up twelve reels, or about 12,000 feet of film, consisting of more than 1,300 shots and 230 separate titles.

For the most part, films had previously consisted of a series of long shots. The camera would stay in a fixed position, recording actors as though they were on a stage. Griffith moved the camera around, shooting a scene multiple times from various angles and then editing the footage to assemble a sequence of action shots that was more compelling, intense, and intimate. With his work, Griffith did more than any other director to legitimize film as art. He insisted that critics and the public move past the conventional view that movies were unworthy spectacles and recognize photo-playsthe term he preferredfor the sophisticated forms of artistic expression that they were. It was a campaign Griffith started in earnest with his new work. Titled The Clansman, this photo-play had been adapted from a popular novel about the Civil War and Reconstruction by southern author Thomas Dixon Jr. In Griffiths hands, the story was transformed into a titanic piece of filmmaking, a game-changer in the making, marketing, and public appreciation of cinema.

Griffith planned the hype for the films launch himself. Ever his own best publicist, he stretched facts in ways that would have made the innovators in the infant field of public relations proud. In the very first notices that announced the special preview in Riverside newspapers, Griffith called himself The Worlds Foremost Motion Picture Producer, and published outright falsehoods to embellish the films feats. Ads reported the movie cost $500,000 to produce and employed 25,000 soldiers in action on battlefield. Both numbers were not even close to being accurate.

Next page