PREFACE

Arizona copper mining camps before the 1950s were not unlike the British imperialoutpostsdescribedby W. Somerset Maugham in his South Sea Tales. Such Arizona townsasMorenci,Jerome, Ajo and Bisbee were isolated, mercantilistic colonies. Therethelaboringmen enjoyed good wages and a variety of comforts, while local administratorscongregatedinatight, friendly cliquemaintained their identities as wardens if not as nabobs.Inthiscircle, as in a military officers club, an atmosphere intimate and casualprevailed.Unlikepillars of the community in more traditional, familiar Americansettings,themine and smelter operators felt no compulsion toward demagogic propriety;theirappointivestatus enabled them to pursue a self-expressive style of life. Too,fromtheiroften cosmopolitan origins and training they had acquired gracious andhedonictastes.These characteristics, together with the natural spontaneity endemictominingcamps, produced a social vitality among the managers and engineers whichcomplementedthestreet-filled celebrations of the camps wage earners.

Remoteness, crudity and the glaring heat of the area were probably the first impressionsof a newcomer to the upper social stratum of a mining town. The daytime image wasquicklysoftenedby the first evening lawn party, garnished with a lavish cold buffet,tinklingiceand gentle laughter. Here tired and overtold dinner party stories weregivennewlife, while bits of benign if not congenial gossip found their audience.Littleknotsof men chuckled as they joked about the round heels of legislators electedtoopposethe influence of the copper companies.

It was in this atmosphere that I heard originally of the Bisbee Deportation. At thetimeitmade no more impression on me than any of the other numerous sensationalanecdotesthatconstituted the routine repertoire of those evening exchanges. Moredetailedaccountssubsequently fleshed out the storyand tweaked my curiosity. Ibegantorealize that something more substantial lay behind the flippant boasts thatwecaughtthose Wobbly deadbeats with their pants down or in those days we tookcareofthings the old frontier way.

Since then, I have come to understand that the amenities of Arizona colonial societywere only a small, visible part of the states colonial experience. Like the proverbialiceberg, the great substance of that experience layout of view. The aim of thisbook is to reveal some of that substance, a part of Arizona history that has toolong remained obscured.

Acknowledgments

Without rival, Anne Beller Byrkit, in every respect, did the most to help bring thisbook into being. Four people, Professors John Niven, Harwood Hinton, Melvyn Dubofskyand Clark Spence, provided extensive and detailed critiques of the various stagesof the manuscript. I am indebted greatly to them for their comments.

After reading the underground version of this book, several other scholars helpedmewith their encouragement and constructive suggestionsto persevere with my work.They include C. L. Sonnichsen, Jim Foster, Bob Houston, Jim Kluger, Marjorie HainesWilson, Earl Bruce White, Joe Park and Beverly Springer.

Other people, many from around the state of Arizona, gave me support, too. In particular,John P. Frank, Platt Cline, John Pintek, Selma Pine, Sam and Judy Goddard, JacquieMcNulty, Tom Miller, David Ward and Bishop William Scarlett deserve my deepest thanksfor their interest, enthusiasm and helpfulness. Marie Webner of the University ofArizona Press has been remarkably patient and understanding and a firm believerin my perspective in this book. I am grateful to the University of Arizona Pressfor effecting publication of this work.

-J. W. B.

PROLOGUE

On September 6, 1901, a half-crazed anarchist fired two bullets into the stomachof President William McKinley. Eight days later McKinley died, and Theodore Rooseveltbecame the 26th president of the United States. This marked the beginning of a newera in American life. Roosevelts presidency signaled, if only superficially, a fifteen-yeardecline in popular support for business and industry coupled with a rising nationalsympathy for labor, farmers and other working-class people.

In the Arizona Territory, as much or even more than across the nation, the Progressivesenjoyeda phenomenal popularity during this period. Before 1901 the Arizona miningindustrysponsored, owned, and directed by eastern corporationseffortlessly manipulatedArizonapolitics and society, making the territory an industrial colony. But suchProgressiveterritorial governors as Alexander O. Brodie, appointed by RooseveltJuly 2, 1902, and Joseph H. Kibbey (1905-09), also a Roosevelt appointee, disturbedtheeasy and absolute control which the corporations had enjoyed for two decades.By1908 middle-class and working-class Arizonans had become a political force intheterritory. These people gained control of the territorial legislature between 1908and 1912. They dominated all twenty-four committees in the 1910 Arizona ConstitutionalConvention, producing a document which Arizona mine operators and conservatives foundradical and deplorable.

Progressive-minded, anti-corporate politics characterized the Arizona State Legislaturefrom1912to 1916. During this period liberals enacted laws which provided for theeight-hourday,womens suffrage, workmens compensation, the right to picket, therecallofjudges, better and safer working conditions and other legislation whichenragedcorporateinterests. In particular, the Progressives enacted taxation lawsdistastefultothe mining companies. By 1916 the copper corporations were so furiouslyfrustratedthatthe mining companies managers, previously often at odds with eachother,organizedthemselves in a counteroffensive against the states liberals, especiallythestatesunionists.

By early summer of 1917, the mining interests controlled the states governor andits legislature, and they owned or controlled most of Arizonas newspapers and banks.In July, as the climax of their campaign, the mining companies took advantage ofwartime hysteria, which had influenced public opinion throughout the nation awayfrom Progressivism to support industrial and governmental repression of unpatrioticliberal dissent and labor agitation.

By 1921 the corporations had reestablished their control of Arizona politics andsociety. But Arizona old-timers carry with them even into the last quarter of thecentury the bitterness of this great labor-management war.

This book is about power: about eastern power sponsoring and manipulating economic,political,socialand cultural life in the American West; about corporate interestsinArizonagaining power, using it, abusing it, losing itand regaining it. Thiscorporatepowerof the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, was so greatandcompleteand sure that someone like Senator William Andrews Clark, the MontanaandArizonacopper baron, could say, I dont believe in lynching or violence ofthatkindunless it is absolutely necessary, and be taken very literally.

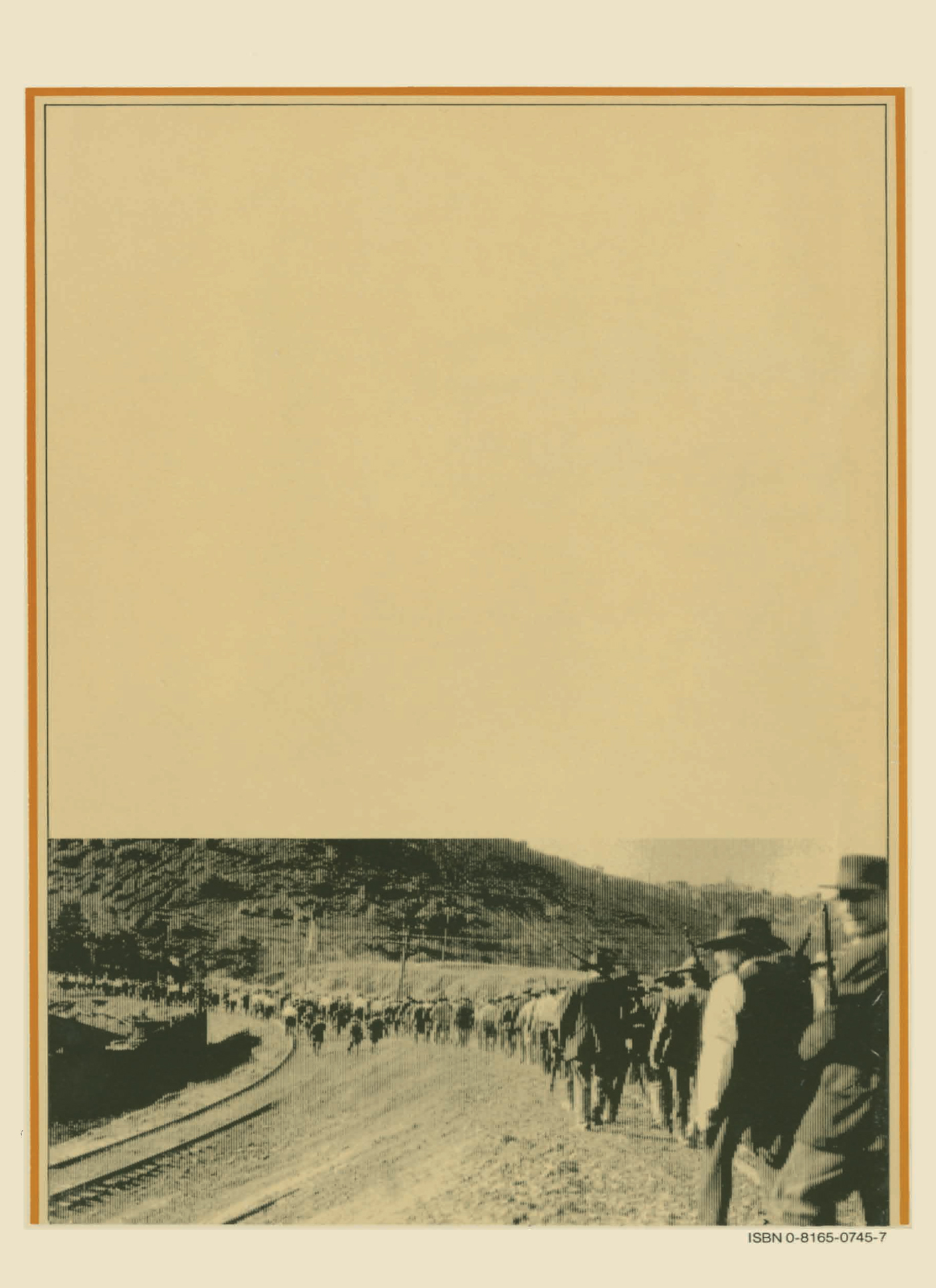

THE BISBEE DEPORTATION OF 1917

In the summertime, bulging, silvery-bottomed cumulous clouds nose northwestward acrosssouthernArizona.Having gathered their cargo of moisture over the Gulf of Mexico,theysailabove the high Sonoran sierras, billowing majestically, their lacy whitecapsreflectingthe sun as they seek the cold air that will condense their burdenandreleaseit in torrential downpours. In July and August, usually in the late afternoon,thecloudsburst and drench the Arizona desert, often to the accompaniment of violentthunderandlightning.