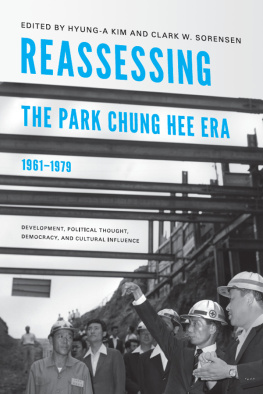

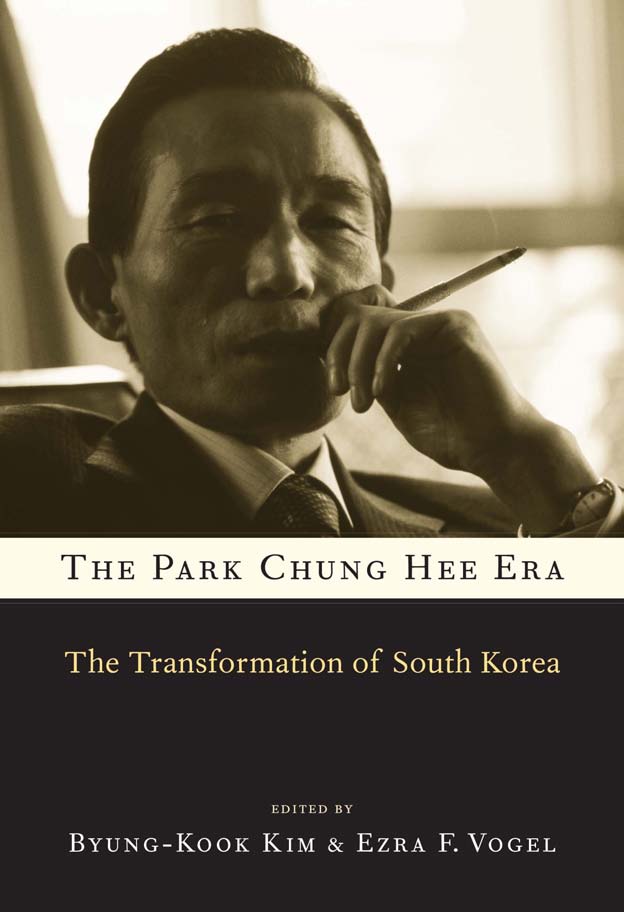

The Park Chung Hee Era

THE PARK CHUNG HEE ERA

The Transformation of South Korea

Edited by

BYUNG-KOOK KIM

EZRA F. VOGEL

HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2011

Copyright 2011 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Park Chung Hee era : the transformation of South Korea / edited by Byung-Kook Kim and Ezra F. Vogel.

p.

cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-674-05820-0 (alk. paper)

1. Korea (South)Politics and government19601988.

2. Park, Chung Hee, 19171979.

3. Comparative governmentCase studies.

I. Kim, Pyong-guk, 1959 Mar. 18

II. Vogel, Ezra F.

DS922.35.P336

2011

951.95043092dc22

2010038046

Contents

Introduction: The Case for Political History 1

Byung-Kook Kim

part one

Born in a Crisis

The May Sixteenth Military Coup

Yong-Sup Han

Taming and Tamed by the United States

Taehyun Kim and Chang Jae Baik

State Building: The Military Juntas Path

to Modernity through Administrative Reforms 85

Hyung-A Kim

part two

Politics

Modernization Strategy: Ideas and Influences 115

Chung-in Moon and Byung-joon Jun

The Labyrinth of Solitude: Park and the

Exercise of Presidential Power

Byung-Kook Kim

The Armed Forces

Joo-Hong Kim

The Leviathan: Economic Bureaucracy

under Park

Byung-Kook Kim

The Origins of the Yushin Regime:

Machiavelli Unveiled

Hyug Baeg Im

Contents

vi

part three

Economy and Society

The Chaebol

Eun Mee Kim and Gil-Sung Park

The Automobile Industry

Nae-Young Lee

Pohang Iron & Steel Company

Sang-young Rhyu and Seok-jin Lew

The Countryside

Young Jo Lee

The Chaeya

Myung-Lim Park

part four

International Relations

The Vietnam War: South Koreas Search

for National Security

Min Yong Lee

Normalization of Relations with Japan:

Toward a New Partnership

Jung-Hoon Lee

The Security, Political, and Human Rights

Conundrum, 19741979

Yong-Jick Kim

The Search for Deterrence:

Parks Nuclear Option

Sung Gul Hong

part five

Comparative Perspective

Nation Rebuilders: Mustafa Kemal Atatrk,

Lee Kuan Yew, Deng Xiaoping, and

Park Chung Hee

Ezra F. Vogel

Reflections on a Reverse Image:

South Korea under Park Chung Hee and

the Philippines under Ferdinand Marcos

Paul D. Hutchcroft

Contents

vii

The Perfect Dictatorship? South Korea

versus Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Mexico 573

Jorge I. Domnguez

Industrial Policy in Key Developmental Sectors: South Korea versus Japan and Taiwan

Gregory W. Noble

Conclusion: The Post-Park Era

Byung-Kook Kim

Notes

Acknowledgments

List of Contributors

Index of Persons

Introduction:

The Case for Political History

Byung-Kook Kim

Few periods have changed South Korean history more than the Park era that began in May 1961 with a military coup dtat. The nature of leadership, the political parties and political opposition, the bureaucracy, the armed forces, relations between workers and farmers and their government, the chaebol industrial conglomerates, foreign policy

all were transformed. Meanwhile, economically South Korea grew out of poverty into an industrial powerhouse in one generation, albeit with massive political, social, and economic costs. And after the Park era suddenly ended in 1979, the reactions to what had taken place transformed the country once more.

The eighteen-year Park era has proved to be one of the most, if not the most, controversial topics for the Korean public, politicians, and scholars both at home and abroad. How much was the economic takeoff fueled by changes in the political and social fabric? To what degree was Park Chung Hee personally responsible for the transformationboth political and economicacross multiple sectors? Why did South Koreas political regime drift toward hard authoritarianism while its economy modernized at a hyper pace? Were these changes causally related? Why was his era marked by both dazzling policy successes and spectacular failures? How much were South Koreas successes and failures explained by its historically antecedent conditions? As one of a handful of newly industrializing countries (NICs) that succeeded in economically catching up with early de

Introduction

2

velopers and militarily building up a system of deterrence, but at huge costs, South Korea is a crucial case in understanding the politics of modernization.

This volume revisits South Koreas developmental era, but it distinguishes itself from other works on the nations rebirth after 1961 by placing its analytic focus on political history. We have chosen political history for three reasons. First, although South Koreas macroeconomic indicators show a country continually undergoing a spectacular industrial transformation, its trajectory of modernization was anything but stable. The macroeconomic indicators covered up a deep sense of insecurity and vulnerability pervading South Korea. The high-payoff, high-risk strategy of subsidizing growth through bureaucratically distributed policy loans burdened banks with huge nonperforming loans, thus entrapping the economy in a cycle of boom and bust and presenting the South Korean leadership with hard policy choices in 1972 and 1979. The volatile swings in this U.S. allys global, regional, and peninsular strategy aggravated or ameliorated South Koreas security dilemmas in 1961, 1964, 1969, and 1976, which triggered its policymakers need to reassess competing budgetary priorities between military and economic programs. Most critical, Park Chung Hee was at first supposed to step down in 1971 and, after a constitutional revision to allow his third presidential term, in 1975. Whether he would do so was to have profound impacts on South Koreas regime character and, hence, its strategy of modernization. The choice made at each of these critical junctures, determining South Koreas subsequent path of economic growth, was heavily shaped by politics.

Second, we focus on political history because at many of the critical junctures, for South Korea to succeed at the state building, military security improvements, and market formation upon which its prospect for hypergrowth depended, the resolution of problems and issues could only come from its top political authorities attempt at juggling the competing claims of geopolitics, geoeconomics, and domestic politics. To explain South Koreas power realignments between state ministries away from its intrinsically conservative Ministry of Finance (MoF) in 1962, 1965, and 1973, or toward the MoF in 1969, 1972, and 1979, we must examine how political leaders controlled state bureaucrats. State ministries, if left alone, only produce a deadlock of interests or a gradual adjustment of interests.1

To explain the chaebol conglomerates risk-taking behavior, one must look into what kind of incentives they had that made taking risks a rational strategy from their perspective and why those incentives were dangled in front of them in the first place. Such inquiries require an analysis of Park Chung Hee and his top aides political goals, calculations, and strategies.

Next page