Copyright 2016 by Peter Bussian

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Rain Saukas

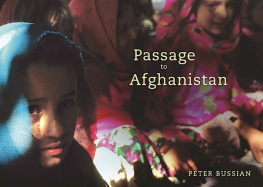

Cover image: Girls in an illegal girls school near Jalalabad in 2001. Under the Talibans rule, girls were officially banned from going to school.

Print ISBN: 978-1-51070-813-6

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-0814-3

Printed in China

For my sons, Max and Leo.

Contents

Introduction

I always dreamed of going to Afghanistanand in May 2001, world events finally conspired to get me there. As a professional photographer and an explorer by nature, I had already traveled and worked in some of the worlds most dangerous and remote places. Because of the romanticized vision I had of Afghanistaninduced by influences as disparate as the writings of Rumi and Kipling, photographs I had seen, and its occasional appearance in the nightly newsAfghanistan beckoned loudly. Back then so little was known about Afghanistan in the West and I wanted to know what life was like on the ground. I wanted to see its deserts, mountains, and cities, and meet real Afghans. I would end up spending much of the next fifteen years there, photographing the land, exploring its terrain, and getting to know its people firsthand.

My first trip to Afghanistan did not disappoint. I was on assignment for the International Rescue Committee (IRC), a New York-based humanitarian aid organization that I had been photographing for in other war-torn countries, most recently in Kosovo and Bosnia. The IRC had asked me to photograph displaced Afghans in the refugee camps in Pakistan and to go into Afghanistan if I was somehow able to get permission from the Taliban, who ruled it at the time. I jumped at the opportunity and after photographing the camps in Pakistan for several weeks, the Taliban amazingly approved my request to photograph Afghanistan. The reason for the approval was twofold: the Taliban wanted me to portray them in a positive light to help counter the negative worldwide publicity they received after destroying the massive ancient Buddha statues in Bamyan Province, which theyd deemed idolatrous; and because many members of the Taliban had positive feelings about the IRC because they had learned English in IRC supported schools.

A Taliban-approved permission to enter and photograph Afghanistan was very rare. When I was handed my visa in the Pakistani city of Peshawar (the Pashtun city where millions of Afghan refugees have lived over the past forty years), the Taliban official, a oneeyed Afghan with an eye patch and an intimidating black turban, told me that they were looking forward to my photographs showing the world the real Afghanistan. For a brief moment I was impressed by the freedom he seemed to be encouraging, but the feeling quickly dissipated with the second half of his statement but remember, no pictures of people or animals . His naive reminder was a directive to adhere to the Talibans interpretation of text in the Koran that they believe forbids the artistic rendering of living creatures. Of course I had no intention of following the directive.

From the moment I drove over the dazzling and storied Hindu Kush mountain range, which separates Afghanistan and Pakistan, and descended into Taliban-controlled Kabul, I was mesmerized and silenced by the desolate, extreme, and harshalmost martiandesert and mountain landscape. The vast, rugged, and minimalist beauty reminded me of parts of Colorado and the American West, where I grew up. Seeing people next to the road and in towns, the fascination Id long held from a distance alighted. The Taliban had a strict dress code: the men all had long beards and wore simple shalwar kameezlong cotton shirts over pantsand monochromatic turbans on their heads; the women, except for the very young or old, dressed in blue or white burkas (called chadris in Afghanistan). Except for their simple rubber shoes and plastic bags, and occasionally an internal combustion engine, nothing indicated that these people existed in the modern world.

There was beauty everywhere in Afghanistan. Yet there was sometimes brutality too: Women being led on donkeys like possessions and hit with sticks; human bodies hanging from light posts; young Afghan boys dressed like girls in the back of Taliban pickups. I soon learned that Afghanistan is a land of stark contrastsa brilliant and complex work of art on a canvas where dark and light contrast sharply. Simultaneously terrifying and exhilarating, it had the mix of raw beauty and danger that I was looking for. I wanted this cocktail and I knew in my gut I would be connected to this place for a very long time.

After leaving Peshawar for Kabul, I traveled overland by car and driver through Pakistans tribal belt, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, a wild no mans land full of fiercely independent Pashtun tribes whose distrust of the Pakistani government dates back to before the 1947 India-Pakistan partition, when the land was the border between Afghanistan and the former British colonial India. The tribes were largely left alone by the British to counter perceived and potential Russian aggression toward India by way of Afghanistan. The border was thenand still isfull of heavily armed Pashtuns who have been a natural buffer to armies from central Asia who might want to invade the Indian subcontinent.

In the South Asian version of the Great Game between the Russians and the British, both countries tried and failed to conquer Afghanistan in the nineteenth century. Russia tried again in the 1980s and was ultimately defeated. The two countries are among the many empires that have tried and failed to conquer Afghanistan. Today, Afghanistan is one of only two countries in Asia that has never been colonized by the West, and one of only a handful in the world to avoid that fatea point of immense pride for Afghans. The unique Afghan mixture of Islam, Pashtunwalithe pre-Islamic honor code of the Pashtunsand other influences from different ethnic groups have certainly helped fuel the indomitable Afghan spirit with its warrior philosophy.

In retrospect, given the events of September 11, 2001, one of the most remarkable things I saw on my journey from Peshawar to Kabul was a sprawling compound near Jalalabad, the largest city in eastern Afghanistan, and on the main highway from Peshawar to Kabul. It was owned by a very wealthy Saudi foreigner whom I hadnt heard of at the time: Osama bin Laden. The fact that I saw bin Ladens compound just months before the attacks on the United States that he masterminded, including the horrific one on my home city of New York, deeply affected me. It is still surreal to me. After 9/11, Afghanistan became the focal point of the Wests War on Terror and Westerners got to know it through the lens of that war, Americas longest. Headlines about Afghanistan became commonplace, and images of death and destruction poured out.