Nina Jankowicz - How to Lose the Information War: Russia, Fake News, and the Future of Conflict

Here you can read online Nina Jankowicz - How to Lose the Information War: Russia, Fake News, and the Future of Conflict full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Bloomsbury, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:How to Lose the Information War: Russia, Fake News, and the Future of Conflict

- Author:

- Publisher:Bloomsbury

- Genre:

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

How to Lose the Information War: Russia, Fake News, and the Future of Conflict: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "How to Lose the Information War: Russia, Fake News, and the Future of Conflict" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Nina Jankowicz: author's other books

Who wrote How to Lose the Information War: Russia, Fake News, and the Future of Conflict? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

How to Lose the Information War: Russia, Fake News, and the Future of Conflict — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "How to Lose the Information War: Russia, Fake News, and the Future of Conflict" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

How to Lose the Information War

How to Lose the Information War

Russia, Fake News, and the Future of Conflict

Nina Jankowicz

This book was prepared (in part) under a fellowship from the Kennan Institute of The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, DC. The statements and views expressed herein are those of the author and are not necessarily those of the Wilson Center.

For the truth tellers

Contents

It was nearly one in the morning in Ukraine, and I was about to tell a roomful of people in Washington that Russian disinformation was keeping me up at night. They had gathered after months of volunteering for Hillary Clintons presidential campaign, acting as a brain trust and sounding board for her foreign policy ideas. From thousands of miles away, I was dialing in from Kyiv. The mood in the room seemed to be one of cautious excitement and relief that the rancorous campaign would be over in a few days. Now, just before the fateful 2016 vote, we discussed the future; how should American foreign policy look in the next administration?

I told the group that Russian online warfare posed a critical threat to the future of democracies around the world. Since moving to Ukraine that September, I had watched as the country attempted to defend itself against Russian attacks, not only on the physical battlefield, but in the information space as well. These attacks showed no signs of letting up here in Ukraine, or across Europe. If anything, online warfare was intensifying. It seemed that every day a Ukrainian was telling me the United States ignored Eastern and Central Europes struggles at its own peril. Information warfare does not respect international borders. It would reach us soon, too.

Its not just Ukrainians Soviet past that gives them clarity about the Kremlins intent, nor is it something that only a nation at war with Russia can understand. Most Estonians, Georgians, Poles, Czechs, Ukrainians, and others in Central and Eastern Europe will tell you that Russia meddles in their domestic affairs. All of them will tell you that this phenomenon is nothing new. The Russian influence campaigns that took the United States by surprise in 2016 have been going on in Eastern Europe for decades and have only been amplified by social media and digital technologies that allow information to spread faster, farther, and with more precision.

The West has finally recognized this threat but has yet to do much about it. In June 2018, more than a decade into Russias information war and nearly two years after the election of Donald Trump, when the Senate Judiciary Committee asked me to testify before them about preventing election interference, most of the Republican senators other than the committee chair, Chuck Grassley of Iowa, cleared out of the hearing room before the witnesses began their presentations. The Democrats werent much better. By the time I finished my oral testimony, in which I praised countries like Estonia and Ukraine for their efforts to put citizens at the heart of [their] responses to disinformation, just Senator Grassley and Democrat Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota remained on the dais for the question and answer session. Disinformation and election interference were enough of a problem to be put on the Senate agenda, but the United States and its organs of power did not seem to grasp the scope of Russias interference across scores of other countries. We have ignored the nuances on the battleground of the information war, casting aside all that the countries in the vanguard have learnedand how often theyve failed.

But I know that solutions exist, having found myself on the front lines of Russias information operations from the beginning of my career. My first job out of graduate school was at the National Democratic Institute for International Affairs (NDI), a nongovernmental organization based in Washington, DC, that was founded in 1983 I worked on the Russia program team. When the US Agency for International Development (USAID) was asked to leave Russia in 2012 after the Russian Foreign Ministry accused it of meddling in Russias political processes (a charge that is even more ironic in hindsight), NDI decided to move its Russia programwhich trained election monitors, political parties, and civil society organizations of many different political backgroundsoffshore to the nearby Baltic states. A few years later, despite having closed its office and de-registered its presence in Russia, NDI was added to a list of undesirable foreign organizations that, according to the Russian parliament, threatened the security of the country. For Russian nationals, interaction with so-called UFOs carried a hefty fine or a jail sentence.

NDI had always been the target of hit pieces by Russian propagandists. But as propaganda about our addition to the UFO list reached a fever pitch, a curious political cartoon appeared on vKontakte, the Russian version of Facebook. In it, four anthropomorphized spheres are speaking to each other. The largest one, emblazoned with the Russian flag, shouts: Go home, you sons of bitches! to two very forlorn spheres bearing the logos of NDI and the National Endowment for Democracy, one of NDIs funders, also targeted by the UFO law. A very small, scared American sphere floats in the background, pleading with Russia to not offend my foundations. The cartoon is not particularly witty, nor was it especially successful; the Studio 13 page that shared it had only about 50,000 followers on vKontakte. But among the cartoons praising Putin and his illegal annexation of Ukraines Crimean peninsula, it struck me that an event of much less significance was given the same stature. Whoever was behind this account wanted to make sure the patriotic Russians who followed the page knew that their government was protecting them from the national security threat that NDI posed through its trainings on participatory democracy. It was clear to me that social media had already become a new battleground for influence. Russia was testing its toolkit at home and in its backyard, and soon it would be ready for prime time, influencing the discourse in the American presidential election.

A year and a half later, in September 2016, I moved to Kyiv, Ukraine. Under a Fulbright Public Policy Fellowship, I worked as a strategic communications adviser to the spokesperson of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Mariana Betsa, the first woman in a position of new significance. For three years, Ukraine had been at war with Russia and Kremlin-backed separatists in the countrys east. Mariana headed up the Ministrys informational offensive. Her Twitter account was under constant bombardment by pro-Russian trolls. She tweeted her daily update about events on the front lines:

Russia continues escalation in Donbas to destabilize UA. 83 attacks by Ru&militants, tanks, mortars used. 1 UA KIA.

Later, she was stunned and disgusted when she received a reply from Graham Phillips, a British citizen whose reporting from Ukraines conflict zone for propaganda network RT (formerly known as Russia today) included the intimidation and berating of Ukrainian political prisoners. Phillips wrote: Marianaare you a liar because you are a political prostitute? Or a prostitute because you are a liar?

Interactions like this were a fairly typical occurrence. Other accounts would pile on, yelling into the digital ether that the Ukrainian Euromaidan protests in 2013 and 2014 were a fascist coup and the new government was driving the country into a hole. Only Russia could save Ukraine, they wrote. The cycleand the tired pro-Russian narratives it containedwas repeated with every tweet that

Relentless, offensive, and misleading tweets were just one facet of Russias information war against Ukraine. Pro-Russian media both inside and outside Ukraines borders reported patently false stories, so much so that Ukraine was home to the first fact-checking operation founded in response to Russian disinformation, created not long after Russia illegally annexed Crimea. Other elements of civil society joined in, using the power of social media to push back about Russian claims of peace on the peninsula, where the native Tatar population was being persecuted; or about the human rights situation in the Donbas; or to mobilize support for troops on the front. Still, the Ukrainian government struggled to match the Russian Foreign Ministrys superior funding and organization, not to mention the narrative power of their lies. These were designed to target weak points in Ukrainian society, exploiting divisive issues like poor governance, corruption, and ethnic and religious tensions, and were repeated by the Russian Foreign Ministry spokesperson and parroted by Russian media on a weekly basis.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

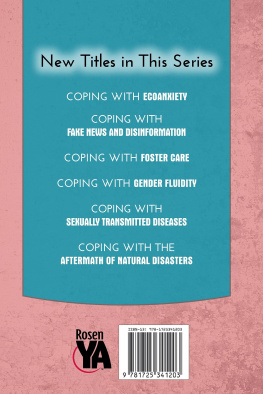

Similar books «How to Lose the Information War: Russia, Fake News, and the Future of Conflict»

Look at similar books to How to Lose the Information War: Russia, Fake News, and the Future of Conflict. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book How to Lose the Information War: Russia, Fake News, and the Future of Conflict and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.