Steven Stoll - Ramp Hollow: The Ordeal of Appalachia

Here you can read online Steven Stoll - Ramp Hollow: The Ordeal of Appalachia full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

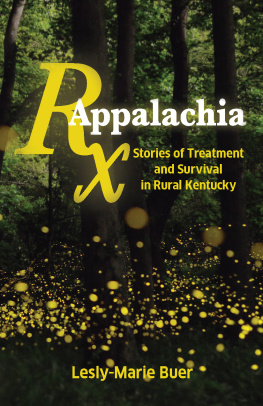

- Book:Ramp Hollow: The Ordeal of Appalachia

- Author:

- Publisher:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Genre:

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ramp Hollow: The Ordeal of Appalachia: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Ramp Hollow: The Ordeal of Appalachia" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Ramp Hollow: The Ordeal of Appalachia — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Ramp Hollow: The Ordeal of Appalachia" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Leslie

The social order is a sacred right Yet that right does not come from nature and must therefore be founded on conventions.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract (1762)

For since we are the outcome of earlier generations, we are also the outcome of their aberrations, passions and errors, and indeed of their crimes; it is not possible wholly to free oneself from this chain. If we condemn these aberrations and regard ourselves as free of them, this does not alter the fact that we originate in them. The best we can do is to confront our inherited and hereditary nature with our knowledge, and through a new, stern discipline combat our inborn heritage and implant in ourselves a new habit, a new instinct, a second nature, so that our first nature withers away.

Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life (1874)

T HIS IS A BOOK ABOUT an American settler culture, how its people hunted, foraged, farmed, and gardened, and how they lost their land. We all learned a version of American history that emphasizes the widening possession of land. That version tells of the brave women and men who voyaged into the wilderness. They did build homes in the wilderness, and they were brave, but in making homes for themselves they took homes from others. Their possession caused the dispossession of Shawnee, Cherokee, Munsee, Creek, and other nations. Many other Americans lost their lands and livelihoods during the last two centuries or were prevented from gaining access in the first place: African-Americans coerced into sharecropping throughout the South after the end of slavery and Mexicans evicted from their ranchos after the takeover of California. Even the descendants of those pioneering settlers were forced to leave their gardens and woods after little more than a century.

I am interested in how people get kicked off land and why we dont talk about them. Americans tend not to think of ejectment and enclosure as central to the history of the United States. In the decades after the pioneers arrived in the mountains, they established families and communities and propelled their sons and daughters into households of their own. Yet when they werent moving westward anymore, they no longer advanced the American Empire. Their story no longer coincided with the one about a nation destined to embrace a continent. They no longer served a particular role in the version of American history we all learned. They continued to grow maize in narrow hollows and graze their cattle in forest openings. But for some reason their persistence became a problem. They entered a period of conflict and decline that is the shadow of another story weve been told, about the Industrial Revolution. The central event in Ramp Hollow is the scramble for Appalachia, or the rapid onslaught of joint-stock companies to attain the rights and ownership needed to clear-cut the forests and dig out the coal. How this happened and what was lost is the subject of this book.

This book is also about country people throughout the Atlantic World over the last four hundred years. By country people I mean settlers , peasants , campesinos , and smallholders , all of whom make their livings by hunting, foraging, farming, gardening, and exchanging for the things they cannot grow or fashion themselves. The general word for them is agrarians . My purpose is to unite the experience of backcountry settlers of the southern mountains with that of agrarians elsewhere, to demonstrate that English peasants in 1650 and Malian smallholders in 2000 shared a similar fate and encountered similar sources of power as Scots-Irish farmers in 1880. My method is to create a thick context around the particular story I tell.

It can be difficult to understand people who live close to their environments. While preparing these chapters, I found critics who said either that agrarians work interminably for little gain or that they dont work hard enough. Both cant be true. The apparent contradiction between futile drudgery and laziness has nothing to do with how much time households spend in their gardens. Instead, these are two ways of saying that such people waste their time and labor no matter what they do. We tend to see settlers, peasants, campesinos, and smallholders as relics of the past. I ask the reader to look at them differently, as inhabiting the same planet and the same moment in time as everyone else. There are no primitives, savages, or backsliders. There are only humans in various social arrangements. I present their way of life, not as unfit or doomed but as functional and legitimate, though often riven with hardship. Yet in the years I spent traveling to libraries and archives where I read all sorts of documents, I often came across an idea that amazed me but that I could not understand, the idea that historical progress required taking land away from agrarians and giving it to others.

* * *

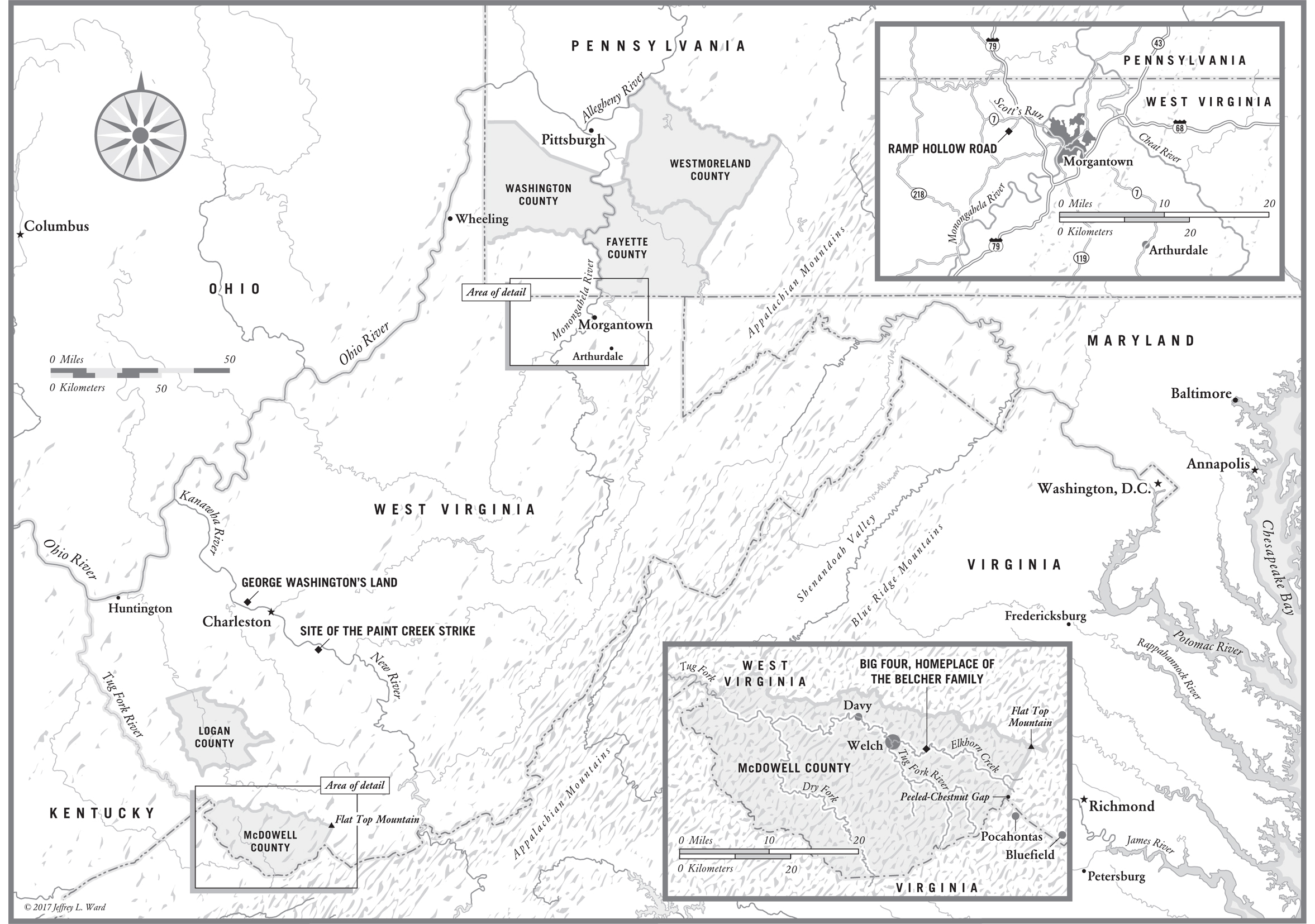

RAMP HOLLOW IS A TRIBUTARY of Scotts Run, once a profitable but now an abandoned coal seam just outside of Morgantown, West Virginia. A few years ago I traveled there with H.R. Scott, an agent for the West Virginia University Agriculture Extension Service. Wed been visiting sites in the area all day when H.R. stopped at a neighborhood that followed a road up a gentle grade. I stepped out of the truck where a trickling branch emptied into a larger creek. While H.R. rested, I walked unhurriedly in the afternoon humidity, after the sun had fallen just below the rim of the tiny valley. It narrowed and steepened, with each house at a slightly different elevation. Behind the houses, trees and brush covered the abrupt inclines that rose to a height of about 150 feet. The bottom of the hollow was just as wide, making it seem like I was walking in the rut of a giant wheel.

Halfway up I came to an abandoned house, older than the others. White windowpanes stood out against red tar paper. A metal roof extended over a pocket-like porch. The windows on one side had fallen in, and I could see things left behind by the last residents. This was a miners shanty, circa 1900. I imagined a man walking out in the morning, a woman with children inside, smoke from the chimney floating to the canopy. An outhouse stood a few feet away, almost over the branch. It reminded me that humans packed close together become intimate with each others waste.

The coal miner who earned the money that supported the family who lived in the tar paper dwelling might have been William Fulmer or Ross Spicer or John Raketskynames from the Census of 1940. Everyone in Scotts Run was a miner or married to one or the child of one. They lived fairly well when wages covered food and rent, but many reported no income for at least one week in 1939. I wondered whether they had once had their own farms or if they had been brought up in Scotts Run. I wondered how they lived when the money stopped. I kept a photograph of that house on my desk while writing this book, next to one of a different house.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Ramp Hollow: The Ordeal of Appalachia»

Look at similar books to Ramp Hollow: The Ordeal of Appalachia. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Ramp Hollow: The Ordeal of Appalachia and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.