Copyright 2018 Elizabeth Catte

All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

First edition 2018

ISBN: 978-0-9989041-4-6

Belt Publishing

1667 E. 40th Street #1G1

Cleveland, Ohio 44120

www.beltpublishing.com

Book design by Meredith Pangrace

Cover by David Wilson

PART I

Appalachia and the Making of Trump Country

PART II

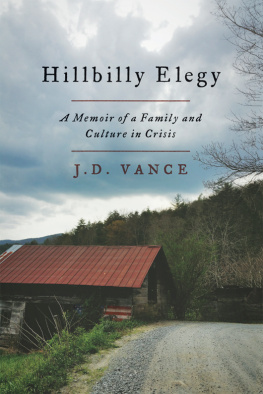

Hillbilly Elegy and the Racial Baggage of J.D. Vances Greater Appalachia

PART III

Land, Justice, People

INTRODUCTION

S ix months before the 2016 presidential election, my partner and I moved from Tennessee to Texas, to a modest-size city best known for housing the largest oil refinery in the United States. It also has the distinction of having some of the highest rates of brain cancer, leukemia, stomach cancer, nervous system and skin disorders, and respiratory ailments in the country.

To convince ourselves that the move hadnt been a mistake, we talked often of our lives in Appalachia, where we lived in the shadow of paper mills, mines, and coal-burning plants. These discussions later became the justification for our sudden departure. We expected culture shock and homesickness in Texas, but we did not anticipate a baptism by sulfur dioxide, hexane, and pentane. If two people raised on heavy metals and slurry call time, its fair to say that things might be fucked. By the time you read this, well be back home.

We longed for home for less clinical reasons as well. In Texas, upon hearing where we were from, everyone wanted to talk to us about a new book called Hillbilly Elegy, by a guy named J.D. Vance. The best-selling memoir of a family and of a culture in crisis, now set to be turned into a film by Ron Howard, had become our political moments favorite text for understanding the lives of disaffected Trump voters and had set hillbillies apart as a unique specimen of white woe. Using the template of his harrowing childhood, Vance remakes Appalachia in his own image as a place of alarming social decline, smoldering and misplaced resentment, and poor life choices. For Vance, Appalachias only salvation is complete moral re-alignment coupled with the recognition that we should prioritize the economic investments of our social betters once more within the region.

Its a strange experience to be grilled about the social decline of your people less than five hundred yards from a refinery that gives poor African Americans cancer, but that is what happened to us. At the local university, people whose wall art had been eaten by pollution were suddenly and deeply fascinated by the tragedies of Appalachia.

Why dont more people just leave? they asked, while we silently calculated how much money wed lose by moving back home. If we were destined to be poisoned by corporations and deprived of civil liberties by corrupt politicians, better the devil we knew, we reasoned.

Election season cast Appalachia as a uniquely tragic and toxic region. The press attempted to analyze what it presented as the extraordinary and singular pathologies of Appalachians, scolding audiences to get out of their bubbles and embrace empathy with the forgotten America before its residents elected Donald Trump. After the election, when it became too late, the pendulum swung in the opposite direction and empathy became heretical. Appalachia, political commenters proclaimed, could reap what it had sown.

Theres not a single social problem in Appalachia, however, that cant be found elsewhere in our country. If youre looking for racism, religious fundamentalism, homophobia, addiction, unchecked capitalism, poverty, misogyny, and environmental destruction, we can deliver in spades. What a world it would be if Appalachians could contain that hate and ruin for the rest of the nation. But we cant.

In the region, we often speak of Appalachia as a mirror that reflects something troubling but recognizable back to the nation. Some cultures avoid mirrors in periods of mourning, afraid that the void created by grief might become a portal that causes something sinister to leak out. These days, an image like this seems fraught with extra meaning.

My partner and I went about our daily lives in Texas trying to convince people that the oil industry and the coal industry werent fundamentally different to the person with undrinkable water. Cataloguing contemporary essays and interviews about the Appalachia problem became something of a hobby for me. I quickly discovered that the most telling aspect of these essays and interviews wasnt what they said about Appalachia, but what they didnt say.

According to the bulk of coverage about the region in the wake of Trumps election and the success of Hillbilly Elegy, currently at fifty weeks on the New York Times Best Seller list, I do not exist. My partner does not exist. Our families do not exist. Other individuals who do not exist include all nonwhite people, anyone with progressive politics, those who care about the environment, LGBTQ individuals, young folks, and a host of others who resemble the type of people youll meet in this volume. The intentional omission of these voices fits a long tradition of casting Appalachia as a monolithic other America.

While many regional groups experience this treatment, as scholar Elizabeth Engelhardt recently wrote in the journal Southern Cultures, Appalachia stands out, however, in the sheer length of time that people have believed it could be explained simply, pithily, and conciselyagain and again Appalachia is relegated to the past tense: out of time and out of step with any contemporary present, much less a progressive future.

With this in mind, What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia has two objectives: to provide critical commentary about who benefits from the omission of these voices, using Appalachian history to push back against monolithic representations of the region, and to openly celebrate the lives, actions, and legacies of those ignored in popular commentary about Appalachia. The critic bell hooks wrote, With critical awareness, we must recognize the spaces of openness and solidarity forged in the concrete experience of living in communities that were always present in radical spaces in Appalachia both then and nowI believe it is essential for unity and diversity to gather those seeds of progressive change and struggle that have long characterized the lives of some individuals.

I am a historian and What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia is filled with history, but it is not a comprehensive primer. Rather, it approaches history as the seeds that hooks describes, and hopes to plant in your mind something that might blossom if you examine the region more closely. This isnt, however, another one of those voice for the voiceless projects. For those who already know and celebrate a different Appalachiaand they are manythis is solidarity.

WHAT IS APPALACHIA?

Appalachia is, often simultaneously, a political construction, a vast geographic region, and a spot that occupies an unparalleled place in our cultural imagination. Well start with the most basic information to get our bearings straight. Appalachia is an approximately 700,000-square-mile region of the eastern United States. It is loosely defined by the arc of the Appalachian Mountains that begins in Alabama and ends in New York, although the mountains continue into Canada.

Next page