Copyright 1972 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-8131-0135-4 (pbk: acid-free paper)

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of American University Presses |

Contents

Part One

The Early Sixties

HARRY W. ERNST & CHARLES H. DRAKE

DAN WAKEFIELD

ROBERT F. MUNN

JERALD TER HORST

RUPERT B. VANCE

Part Two

Between a Rock & a Hard Place

ROBERT COLES

T. N. BETHELL, PAT GISH, & TOM GISH

JAMES C. MILLSTONE

T. N. BETHELL

BEN A. FRANKLIN

CALVIN TRILLIN

T. N. BETHELL

DAVID B. BROOKS

JAMES S. BROWN

BILL MONTGOMERY

JAMES S. BROWN

Part Three

Lessons in Fighting Poverty

THOMAS PARRISH

K. W. LEE

JEANNE M. RASMUSSEN

PAUL GOOD

CALVIN TRILLIN

K. W. LEE

DON WEST

Part Four

Can We Get There from Here?

PETER SCHRAG

JAMES BRANSCOME

JOHN FETTERMAN

PHILIP YOUNG

HARRY M. CAUDILL

ROBB BURLAGE

Preface

More than ten years have passed since John F. Kennedys visit to West Virginia during the campaign for the 1960 presidential primary, the visit which precipitated a declaration of war against the social, economic, and human problems of the Appalachian Region. Ten years have passed since the research was carried out which led to the publication of The Southern Appalachian Region: A Survey.

In that volume, and in a later article reprinted in this book, Rupert Vance suggested a decennial follow-up on the problems and progress of the region. How far have we come in ten years? There is no study comparable to the survey on which to rely for an assessment. Despite the absence of quantitative data, despite the lack of scholarly research on the matter, information is available which could lead us to a tentative answer. This information is found in the observations, impressions, and evaluations of journalists, field workers, local residents, politicians, and social scientists who have lived with, worked with, watched, and written about the problems they have seen and the programs established to cope with them. These mostly frontline reports come in a variety of published forms, from national literary magazines to action-group house organs, from articles in famous dailies to letters to the editors of county weeklies. What follows is a selection of such reports about what happened in Southern Appalachia in the 1960s.

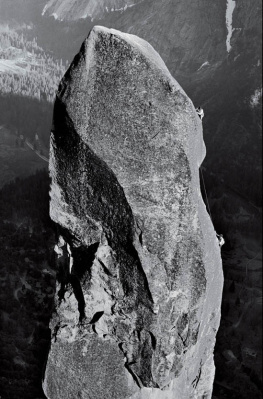

The Appalachian Region is itself an elusive entity, as can be seen from the number of conflicting definitions given it by scholars, reporters, natives, and politicians over the years. How many counties in which states are included? For the most part, we are concerned here only with the southern portion of the region, and within that portion we have concentrated mainly on the coalfields of West Virginia, eastern Kentucky, southwestern Virginia and north-central Tennessee. These are the areas that first attracted the attention of the nation in the early sixties; they seem to have been the places where there was the greatest depression, the greatest concentration of antipoverty efforts, the most heightened response to local, state, and federal programs, and the greatest degree of organization around common interests by the end of the decade. What has been written about central southern Appalachia applies in varying degrees to mountainous areas which are further north or south, lower in altitude or more piedmont in nature, based more on agricultural economies, or which have not had the complicating factor of coal added to their otherwise broadly comparable histories. It should certainly not be thought that places like western North Carolina and much of eastern Tennessee are not truly Appalachian in their culture, character, and problems; it is only that less is known about them, and that what is known suggests that settlement patterns, economic history, and current prospects are different enough for other Appalachian subregions to require a separate accounting. Something registers when you tell many Americans about places called Hazard and Bluefield, but who knows of Spruce Pine or Erwin? The presence of coal seems to be an important common denominator of central southern Appalachia, and perhaps it is coal that has made this area unique, both in its history and in its uncertain future.

Mass unemployment caused by mechanization in the coal industry forced Appalachia to the attention of the nation at the beginning of the sixties. Theorists of the automation revolution prophesied that Appalachia foreshadowed a national employment crisis. Hazard became a symbol for the New Left of the sixties as Harlan had been for the old Left of the thirties. The violence associated with the roving picket movement in eastern Kentucky dramatized the need for intervention by the federal government. By the end of the decade it became clear that coal had been one of the most labor-intensive, technologically backward sectors of the economy, and the Appalachian crisis had not been as representative of the national economy as some had imagined. The roving picket movement thus turned out to be the last gasp of the old era of labor struggles in the mountains. The movements of the later sixties, in contrast, were premised on the existence of a mechanized mining industry and a permanent welfare state designed to care for the industrys casualties.

The Area Redevelopment Administration, established in 1961 with a program for stimulating private industrial development, quickly proved inadequate to the problems of depressed areas in America. The Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 packaged a patchwork of liberal proposals, including a public employment program disguised as work experience and training, and the dramatic Community Action Program with its call for maximum feasible participation of the poor. The much criticized work experience program, concentrated disproportionately in eastern Kentucky, managedtogether with the food stamp programto defuse the violence that had haunted the coalfields in the early sixties.