Chapman - Prove it on me new Negroes, sex and popular culture in the 1920s

Here you can read online Chapman - Prove it on me new Negroes, sex and popular culture in the 1920s full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: New York;Auckland etc;Oxford (GB);United States, year: 2012, publisher: Oxford University Press, Incorporated, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Prove it on me new Negroes, sex and popular culture in the 1920s: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Prove it on me new Negroes, sex and popular culture in the 1920s" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Chapman: author's other books

Who wrote Prove it on me new Negroes, sex and popular culture in the 1920s? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Prove it on me new Negroes, sex and popular culture in the 1920s — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Prove it on me new Negroes, sex and popular culture in the 1920s" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

In writing Prove It On Me, I have benefited from the great wealth of scholarly mentorship, personal support, and financial assistance I have received throughout my education and work at multiple institutions. At George Washington University, new colleagues and mentors William Becker, Nemata Blyden, Linda Levy Peck, Eric Arnesen, and Jenna Weisman Joselit have offered much-needed advice about the review and publication processes at crucial moments. I thank the deans office of the Columbian College of Arts and Sciences and the History Department at George Washington University for allowing me a leave during my first year of employment which was absolutely necessary for the completion of the manuscript.

I spent that leave year supported by a Ford Foundation Diversity Postdoctoral Fellowship at Princeton Universitys Center for African American Studies under Tera Hunters mentorship. Ever since Tera agreed to chair the panel I organized for the 2005 Berkshire Conference on the History of Women, she has been a valued mentor offering advice and support on everything from navigating the job market to replying to readers reports. She read various versions and pieces of this book throughout its evolution, and it is much better for her keen eye and hard questions. Tera is one of a group of women scholars across the academy, including Ula Taylor, Nan Woodruff, Nancy Bercaw, Sue Grayzel, Sharon Holland, Estelle Freedman, Michelle Scott, and Jennifer Baszile, whose mentorship has sustained me and facilitated my growth as a scholar. Each offered a word of advice and a warm personal interest in my success at crucial moments, and I thank them for these significant gifts.

The three years I spent at the University of Mississippi enriched my understanding of race politics and my scholarship in innumerable ways. For the historian, Mississippis social matrix of race, class, nostalgia, repression, and modern aspiration presents a particularly fascinating enigma. Colleagues and friends in the History and African American Studies departments joined me in puzzling over it. Nancy Bercaw, Angela Hornsby-Gutting, Ethel Young-Minor, and Sue Grayzel provided reassurance and advice that first year as I learned to lecture while also maintaining my research and writing. I particularly thank Sue for organizing a womens writing group among history department faculty that proved so helpful in reading chapter drafts, book proposal drafts, and other materials along the way to publication. I thank Sue also for her faith that Prove It On Me would indeed be published and for her steadfast belief in the efficacy of cultural history. I must also thank Dean Glenn Hopkins and Chairs Joseph Ward of the History Department and Charles K. Ross of the African American Studies Department for their support of this project. Dean Hopkins provided me with two College of Liberal Arts Summer Research Grants that allowed me to devote the summer months to additional research and revision of this book. Chairs Joe Ward and Chuck Ross granted me course releases, provided limited enrollments, funded conference and research trips, and provided salaries for teaching and research assistants over the years. Thanks are also due to teaching and research assistant Telisha Dionne Bailey, whose hard work and dedication facilitated my revision process.

Prove It On Me initially emerged in the seminars I took as a graduate student in history and African American studies at Yale University. As the project evolved to the dissertation stage, it benefited from the stimulating interdisciplinary community of established and student scholars of race, gender, and ethnicity across the programs in African American studies, American studies, and history. My dissertation committee, Matthew Frye Jacobson, Hazel V. Carby, and Jonathan Scott Holloway, formed an ideal trio, challenging and pushing my work from distinct but complementary scholarly directions. Their support has been invaluable, and I continue to appreciate their friendship and advice. As one of my examiners, Paul Gilroy challenged my limited, Americanist views through his vast and varied knowledge of the history and politics of the Atlantic world. My work on race in the United States is richer for his perspective. While she was still at Yale, Nancy Cott directed one of my first independent research projects on the way to Prove It On Me and later included me in the Mellon Dissertation Seminar in Gender History she conducted at Harvard University in the summer of 2002. Robin Hayes, Besenia Rodriguez, Joshua Guild, Mary Barr, and Aisha Bastiaans formed a dissertation group useful to the early stages of the book.

My early work on Prove It On Me was also sustained by communities of scholars beyond Yale. Stphanie Larrieux at Brown University organized the initial meeting of the Ivy League Women of Color Dissertation Collective, which became a vital space of scholarly and personal sustenance for my development as a scholar of race, gender, and black womens history. Since I was an undergraduate at Stanford University, the Mellon Mays University Fellows program, the gift that keeps on giving, has provided me funding, crucial sources of career advice, early experiences in conference presentations, and a diverse, far-flung, multigenerational community of scholars. So great is the MMUF network that I cannot list here all the mentors, colleagues, and friends it has granted me, but I duly thank them all. Clayborne Carson and Estelle Freedman were my MMUF mentors at Stanford, guiding my earliest scholarly endeavors in race and gender history. I hope they are sufficiently proud of the scholar I have become to take credit for my work, as Clay once joked.

Over the years of its evolution, Prove It On Me has been supported by numerous foundations and programs. The Ford Foundation Diversity Fellowship program funded my scholarship at both the pre- and post-doctoral stages. The Yale University Sterling Prize Fellowship supported me while I undertook course work in the first years of my graduate program. The Mellon Foundation and the Social Science Research Council provided money for research travel and materials. A Graduate Student Fellowship at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library allowed for a summers immersion in its James Weldon Johnson Collection. The American Association of University Women Educational Foundation supplied an American Dissertation Fellowship that supported my first year of sustained writing.

I spent the final year of dissertation work as an Africana Research Center Pre-Doctoral Fellow in History at Pennsylvania State University. There I met and was generously mentored by a number of smart and engaging historians. Nan Woodruff demanded that I break my writing hibernation to attend her fun and delicious dinner parties. Lori Ginzberg took me out to lunch and discussed the ins and outs of the professoriate and its gender politics. Anthony Kaye took time out of his busy schedule to read and offer great advice on the first chapter of this book. I thank all of them for their friendship and counsel. I must also thank the Center for Ethnic Studies and the Arts at the University of Iowa for sponsoring me as a Junior Fellow at its Junior Faculty Publication Workshop on Women of Color in Popular Culture.

My work as a scholar, writer, and teacher has been made easier by the dedication and invaluable knowledge of departmental staff. Geneva Melvin and Janet Giarratano in the Department of African American Studies at Yale and Michael Weeks and Evelyn Williams in the History Department at GWU have facilitated this book by helping me navigate institutional bureaucracies and providing the rare professionalism so necessary to the success of the academy. I heartily thank them.

Friendships made and kept long before, within, and beyond the academy have shaped me and my vision, carried me through the hard times and helped me enjoy the good times and thus made my ongoing work both possible and (mostly) enjoyable. Talesha Reynolds, Zakiyyah Langford, Claudia Aranda, Kimberly Juanita Brown, Brandi Hughes, Franoise Hamlin, Marcia Chatelain, Melissa Stuckey, Muna Meky, Nancy Bercaw, Nicole Biggers, and Tasha Curry-Corcoran all know the value of being girls together, at any age. I thank them all for their sisterhood and for knowing (or learning) not to ask when I would finally be done with this book.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

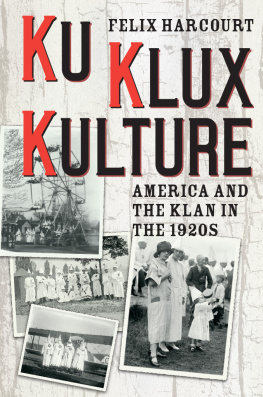

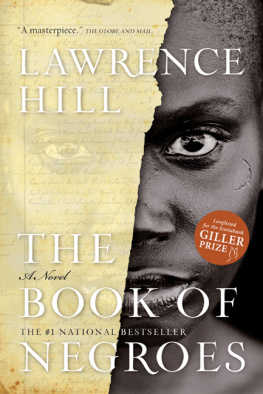

Similar books «Prove it on me new Negroes, sex and popular culture in the 1920s»

Look at similar books to Prove it on me new Negroes, sex and popular culture in the 1920s. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Prove it on me new Negroes, sex and popular culture in the 1920s and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.