About Island Press

Since 1984, the nonprofit organization Island Press has been stimulating, shaping, and communicating ideas that are essential for solving environmental problems worldwide. With more than 1,000 titles in print and some 30 new releases each year, we are the nations leading publisher on environmental issues. We identify innovative thinkers and emerging trends in the environmental field. We work with world-renowned experts and authors to develop cross-disciplinary solutions to environmental challenges.

Island Press designs and executes educational campaigns, in conjunction with our authors, to communicate their critical messages in print, in person, and online using the latest technologies, innovative programs, and the media. Our goal is to reach targeted audiencesscientists, policy makers, environmental advocates, urban planners, the media, and concerned citizenswith information that can be used to create the framework for long-term ecological health and human well-being.

Island Press gratefully acknowledges major support from The Bobolink Foundation, Caldera Foundation, The Curtis and Edith Munson Foundation, The Forrest C. and Frances H. Lattner Foundation, The JPB Foundation, The Kresge Foundation, The Summit Charitable Foundation, Inc., and many other generous organizations and individuals.

The opinions expressed in this book are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of our supporters.

Island Press mission is to provide the best ideas and information to those seeking to understand and protect the environment and create solutions to its complex problems. Click here to get our newsletter for the latest news on authors, events, and free book giveaways. Get our app for Android and iOS .

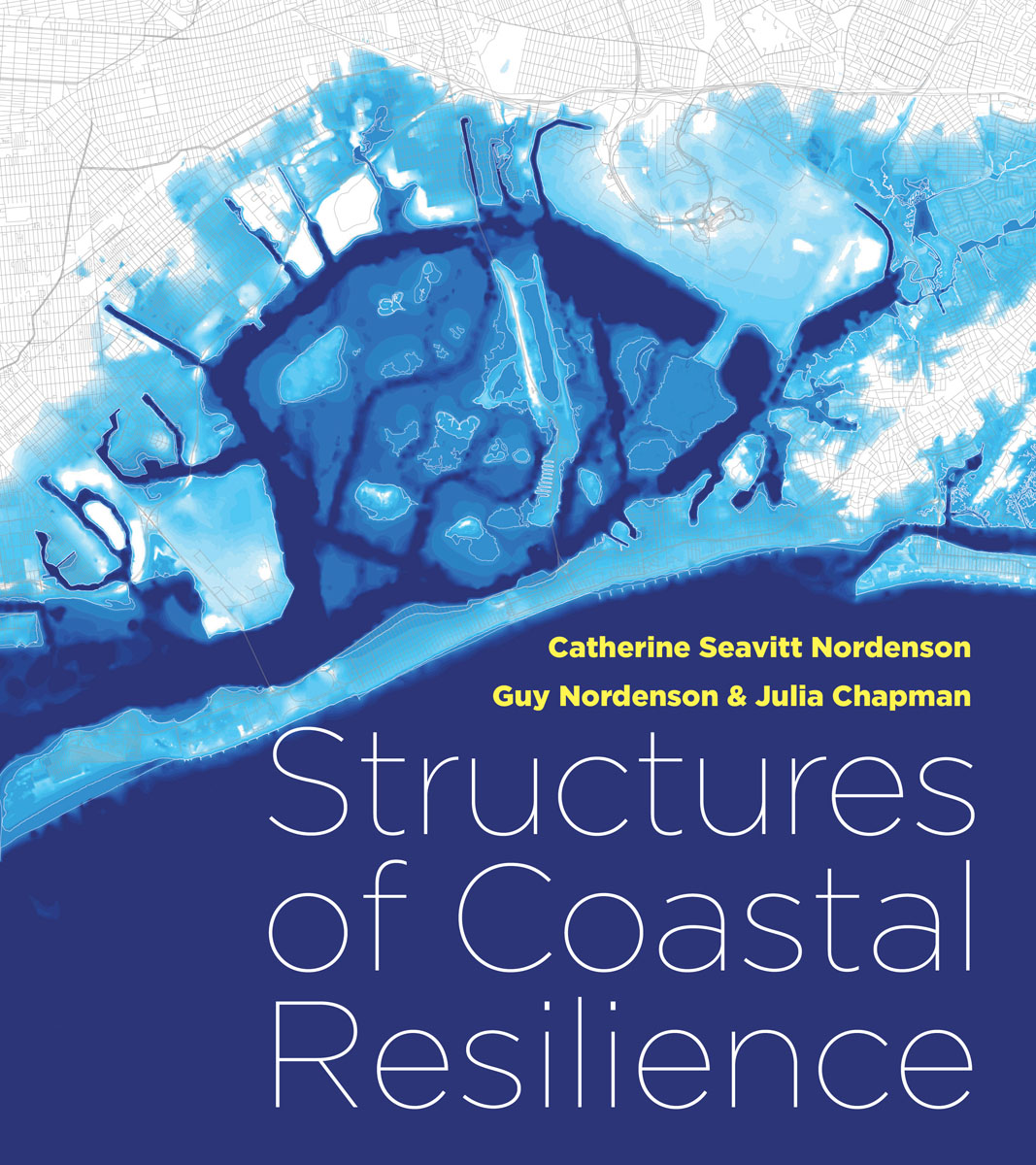

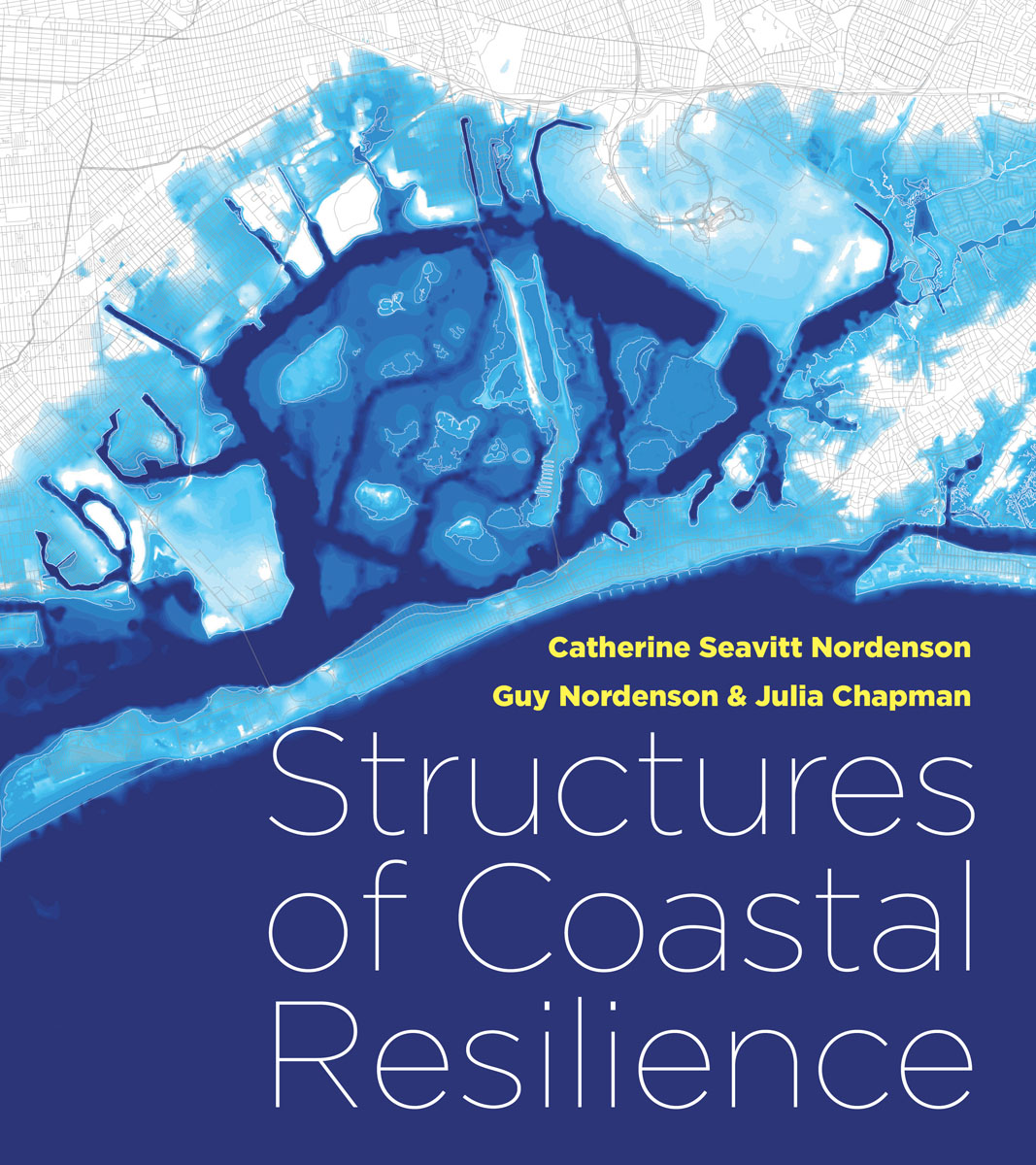

Structures of Coastal Resilience

2018 Catherine Seavitt Nordenson, Guy Nordenson, and Julia Chapman

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher: Island Press, Suite 650, 2000 M Street, NW, Washington, DC 20036

ISLAND PRESS is a trademark of the Center for Resource Economics.

Keywords: Adaptation, adaptive management, climate change, Coastal Storm Risk Management (CSRM), Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), flood risk, floodplain management, National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), nonstructural flood risk management measures, sea level rise, storm surge, United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), United States Geological Survey (USGS), vulnerability, water quality, wetland

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017958675

All Island Press books are printed on environmentally responsible materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

Foreword

by Michael Kimmelman, architecture critic, The New York Times

Afterword

by Jeffrey P. Hebert, vice-president for adaptation and resilience, The Water Institute of the Gulf

Foreword

Michael Kimmelman

ARCHITECTURE CRITIC, THE NEW YORK TIMES

A while back, having dragged a borrowed kayak out of the Los Angeles River, I called a friend in West Hollywood whom I had arranged to meet. I told him I was running late. My trip had taken longer than Id anticipated, and I was soaking wet in a remote stretch of woods. He fell silent for a long time.

What river? he finally said.

The Los Angeles River, around which the city first evolved, can be a dim concept even for lifelong Angelenos. What may vaguely come to mind is the concrete basin from Terminator 2, glimpsed from the Sixth Street Bridge: the area, downtown, that the United States Army Corps of Engineers canalized many decades ago after a series of floods socked the city. Much of the rest of the river, including the part where I kayaked, has long been obscured by rail tracks and highwaysthe neglected backyard in poor East Los Angeles and other neighborhoods.

This is because the Army Corps techno-bureaucratic attitude for much of the twentieth century, like the attitude of most public officials, was that water was an enemy. It needed to be subdued, sequestered from valuable real estate. Hydrologic solutions demanded hard structuresrevetments, bulkheads, and levees. There was next to no concern for how cities and regions might live with nature rather than fight against it; how the destruction of coastline, marshes, and floodplains might come back to bite us; and least of all, little or no thought given to design or aesthetics (landscape architecture seemed frilly and expensive). As a consequence, in a city such as Los Angeles, millions of people ended up cut off from the river, many from jobs, the urban fabric sliced up in ways that isolated vulnerable neighborhoods.

There is no bigger challenge today than the management of coastal ecologies. With climate change, this challenge has begun to take on an existential dimension, threatening the whole global economy and the stability of nations. Hurricanes, heat waves, and floods that used to be rarities are becoming the new normal. The majority of people on Earth today live on or near coasts, a number swiftly escalating in this first urban century in human history, with coastal population densities twice the world average. Most of our largest cities are coastal megalopolises, and their growth (from Houston to the Pearl River Delta, Miami to Jakarta) has involved runaway development, with vast, critical swathes of mangrove, wetlands, prairies, and forests, which mitigate the impact of storms and rising seas, ripped out to make way for miles and miles of concrete and asphalt.

At the heart of this book is the role design needs to play in devising new approaches to coastal resilience. As weve witnessed over and over, we cant simply continue to battle nature with walls and gates. They wont suffice, and theyre often counterproductive. The book rethinks structural solutions to mean more than things built out of concrete and steel. There also need to be structures in place for dealing with politics and people. The book embraces an emerging paradigm shift toward risk management, encouraging climate scientists and engineers to team up with designers, planners, and community leaders. Its goal is to replace dated concepts of flood control with strategies for controlled flooding: hard infrastructure, which is never infallible, with a mix of hard and soft tactics that can produce all sorts of benefits aside from keeping peoples feet dry and property safe.

This is in keeping with a broader shift in progressive thinking that has taken place during the twenty-first century. In cities such as Rotterdam, Madrid, Seoul, and New York, waterfronts are being recuperated, turned into parks, and treated as assets, not obstacles. The movement to include ecological and landscape design into strategies for coastal resilience has run headlong into entrenched politics, neoliberal economics, and a very common human desire to live wherever we want, never mind the consequences, but it has been gaining a voice in America at least since Hurricane Katrina. Now it has penetrated thinking at many architecture schools and government agencies, including the Army Corps, which remains a cumbersome and often counterproductive player but has shown itself to be more open to evolving ideas about coastal protection and water management, even at sites such as the Los Angeles River, where social and economic logic dictates that neighborhood revitalization go hand in hand with wetland restoration and new infrastructure for capturing water. This is because the huge, drought-plagued city can no longer afford simply to dump billions of gallons of water from the river into the ocean. Frank Gehry is the latest architect to join in this effort, a sign of recognition that architecture and design are integral to progressive resilience planning.

Next page