Contents

It is nearing the end of a Friday evening in the medical assessment unit, and lying on the trolley in front of me is a 47-year-old man who has attended complaining of breathlessness and a sharp left-sided chest pain. I am tired and want to go home, but even as a consultant, I am made anxious by the knowledge that chest pain is one of the banana skins of our profession.

As much as any other, this situation reflects the challenges we face many times a day: What clinical information do I need to glean from my history and examination? What clinical decision tools should I use? What diagnostic tests should I subject my patient to and how confident can I be in them? When I finally make the diagnosis, what is the best treatment?

The ability to interpret the evidence and the guidelines that already exist and the new ones that are published every month, and to do this in a way that leaves enough time to actually see some patients, is challenging. We need to remember that our desire to know how to treat our patients better should drive our aim to understand evidence-based medicine (EBM), and then an understanding of EBM should drive improvements in patient care.

Before we begin trying to work out how to dissect various papers, we need to understand how research is divided into different types, and which types are best for answering which questions.

TYPES OF PAPERS

Reading through the medical literature, it will not take you long to realize that there are a number of different types of studies out there the EBM world is not just randomized controlled trials (RCTs), diagnostic studies and meta-analyses.

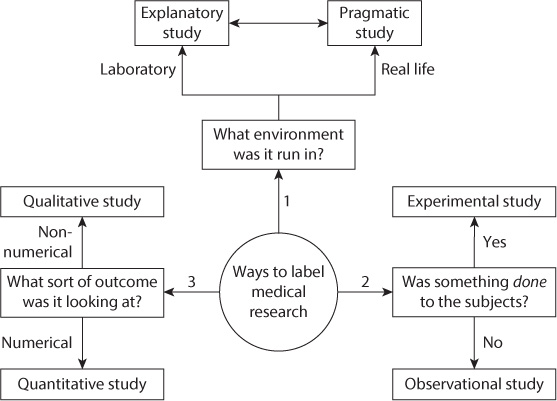

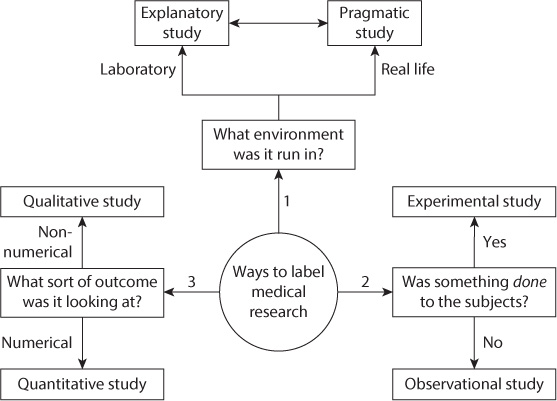

The way different study types are grouped together depends in some part on whom you speak to, but we find the following to be useful in ordering our thoughts when it comes to the different types. Think about three questions:

What sort of environment (a clinical laboratory, a highly controlled but still clinical setting, a normal ward or general practitioners surgery, etc.) is the trial being performed in?

What sort of results are the researchers interested in? Is it a result like mortality rate or blood pressure which will provide a numerical value, or is it a subjective feeling or description of outcomes and emotions which cannot be reduced to a numerical value (qualitative research)?

FIGURE 1.1 Different ways to label a trial three questions to ask.

Are the researchers planning to do something to the patient, for example, give them a new drug or do a new diagnostic test, or are they just observing what happens to them?

The answers to these three questions should then allow us to describe the trial as explanatory or pragmatic, qualitative or quantitative and experimental or observational (). Remember that these labels are not exclusive, and so it is possible to have, for example, a pragmatic, qualitative, experimental trial. The labels simply allow us to begin to order our thoughts about what has gone on within the trial.

QUESTION 1: WHAT SORT OF ENVIRONMENT WAS THE TRIAL RUN IN?

As a rough rule clinical trials can be run in two sorts of places: highly controlled settings such as research laboratories (often with carefully selected, specific patients) or actual clinical settings that are more prone to the normal variations in atmosphere, patients, time of the day and staffing levels. Explanatory research is conducted in the more highly controlled environment and gives the best chance of seeing if the intervention actually works if as many as possible outside influencing factors are taken out of the equation. Pragmatic research, however, is performed in a setting more like a clinical environment (or actually in a clinical environment) and gives a better idea of whether the intervention will work in the real world. Clearly there are a variety of settings in which, and patient types on whom, studies can be performed. It is wise to consider the type of study as being on a spectrum between the explanatory and pragmatic; the more tightly controlled the conditions of the study, the closer to being explanatory and vice versa.

QUESTION 2: WHAT SORT OF RESULTS ARE THE RESEARCHERS INTERESTED IN?

Whether the result that is generated is a hard clinical number such as blood pressure, height or mortality rate or is instead something less quantifiable like sense of well-being or happiness is our second way of dividing up research. Quantitative research will generate numbers such as difference in blood pressure or mortality, which can then be analyzed to produce the statistical results that we talk about later in the book and which form much of the published results from medical literature. Studies that produce a result given as a description which cannot be boiled down to numerical data (such as opinions, explanations of styles of working and why people do not follow best practice, emotional well-being or thoughts and feelings) are termed qualitative research and can be harder to succinctly analyze and summarize. However, there are established ways of looking at this type of paper to ensure that it is as rigorously conducted as quantitative research. See for information on this increasingly important subject. However, in many studies looking at what you might think of as qualitative outcomes (quality of life being a good example), scoring systems have been developed so that a quantitative result can be recorded (and hence analyzed in a statistically clearer way).

QUESTION 3: ARE THE RESEARCHERS PLANNING TO DO SOMETHING TO THE PATIENT?

The final way for us to define the type of research is by whether the researchers intervene in the patients care in any way. In RCTs and in diagnostic studies (both of which we talk about in detail later), but also in other types of study, we take a group of subjects or patients and apply a new treatment, intervention or diagnostic test to their care. These sorts of studies are termed experimental studies. Studies where the researchers look at what happens to a group of subjects or patients but the care that they receive is influenced only by normal practice (and normal variations in practice) and not by the researchers are called observational studies. Surveys, case reports, cohort studies, case control studies and cross-sectional studies are all observational studies, whereas RCTs and diagnostic studies are both experimental studies.

There are a number of different kinds of each type of study, whether experimental/observational, pragmatic/explanatory or qualitative/quantitative. A description of the main features of the important types of studies can be found in the Glossary, and an overview is given in . The type of study that the researchers perform should be decided before they start and should be based on the strengths and weaknesses of each type of possible study.

Finally, we need to mention secondary research. Although single papers can be highly valuable, often greater value can be derived from combining the results or knowledge from a number of papers. Results of different studies can be brought together in review articles, systematic reviews or meta-analyses, all of which we discuss later in the book.

TABLE 1.1

Different Types of Experimental Studies

Randomized controlled study (RCT) |