This book collects a series of Tribune articles that began in November 2010, establishing how lawmakers rigged the Illinois pension code to benefit a chosen few, then demonstrating how the system as a whole was abused time and again for short-term political gains, leaving the states pension funds in the worst shape by far in the country.

The Tribune went on to disclose that Chicago-area union officials were allowed to receive six-figure public pensions based on their fat union paychecks, even as they continued making big money running the unions. The stories led one top-ranking union leader, Tim Foley, to resign and federal authorities began a criminal investigation into how nearly a dozen union officials became eligible for inflated city pensions.

In the state legislature, the work triggered bills that would stop the practice of basing public pensions on heftier union salaries, prevent union leaders from double-dipping on union and public pensions, and cut off the benefits of two teachers union lobbyists who were able to join the pension system after one day of substitute teaching work. Gov. Pat Quinn also has pushed state lawmakers to work with him to solve the states broader pension crisis.

Meanwhile, federal authorities began a criminal investigation into how nearly a dozen union officials became eligible for inflated city pensions, with the Chicago municipal employees and laborers pension funds each receiving subpoenas from a federal grand jury.

PART 1: HOW WE GOT HERE

In November 2010, the Tribune broke the story that high-ranking union leaders and politicians had been abusing the Chicago public pension system for years, siphoning off funds for their own political and personal gain. Though problems with Illinois public pension funds had been well documented, this was the first investigation to trace the pension crisis in Chicago specifically back to its roots in backroom deals by high-ranking officials.

Chicagos public pension funds are racing toward insolvency in large part because city officials and union leaders repeatedly exploited the system, draining away billions of dollars in the last decade to serve short-term political needs, a 2010 Tribune investigation found.

Time and again, the funds have been used as a bargaining chip or a piggy bank. Politicians trimmed budgets by offering early retirement incentives and greased union contract deals with increases in benefits. Pension holidays allowed the city to avoid paying into workers retirement funds.

As a result, the funds soon may not be able to keep promises that are codified in the state constitution, threatening the retirements of tens of thousands of union members and leaving taxpayers on the hook for billions of dollars owed to teachers, police officers, firefighters and others.

A Tribune review of legislative changes pushed by city officials and union leaders from 1995 to 2010 found that laws governing city pension funds contributions and benefits have been changed nearly 40 times, often with little discussion of the financial consequences.

In most cases, pension fund managers had no idea how much the changes ended up hurting them. But in 10 that the Tribune was able to track, the impact on pension funds was more than $3.6 billion.

Those losses, together with Illinois fundamentally flawed pension funding process and poorly performing investments, have driven the unfunded liabilities of the eight pensions funded with city tax dollars from about $3.3 billion in 2000 to at least $20 billion a staggering 500 percent increase.

Even if all retirement benefits were cut off today, every man, woman and child in Chicago would owe more than $7,000 to cover obligations already incurred an amount that doesnt include state pension debt of about $60 billion.

Whats happened in Chicago is a reckless disregard for the next generation of taxpayers and workers, said Jeremy Gold, a national pension expert who advises public and private pension funds. Their birthright has been sold out from under them because theyll be paying for services and benefits that were rendered before they grew up while theirs are cut to save money.

Chicagos pension crisis threatens to stain the legacy of Mayor Richard Daley, who has been at the helm of city government for the past two decades and appoints some of the trustees to the citys pension boards.

The citys chief financial officer, Gene Saffold, said the problems facing the citys public pension funds are not unique to Chicago and have been driven by the worst economic climate in more than 70 years. He said the possibility of the funds running out of money is purely hypothetical and speculative.

Its the citys goal to ensure the funds remain solvent without additional burden to the taxpayers, he said in a written response.

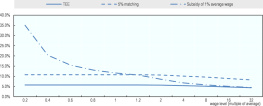

It hasnt always been this way. The pensions were run successfully for decades and, just 10 years ago, were relatively well-funded. The teachers pension was close to 100 percent funded in 2000. Municipal workers had funding levels above 90 percent. City laborers had enough assets to cover 133 percent of their liabilities.

By the end of 2010, however, not one of the pensions funding levels will be above 70 percent. The police and fire funds are already below 40, and the municipal fund is below 50. Pension experts say funding levels below 80 percent place the viability of pensions in jeopardy and are nearly impossible to overcome without massive borrowing, painful tax increases, cuts to benefits and increased contributions.

While Illinois broken pension system has captured headlines across the country, comparatively little attention has been paid to the looming crisis in Chicago.

The citys pension funds were set up to provide retirement security for tens of thousands of city workers. Most dont participate in the federal Social Security program, and the vast majority receives modest benefits averaging about $40,000 a year.