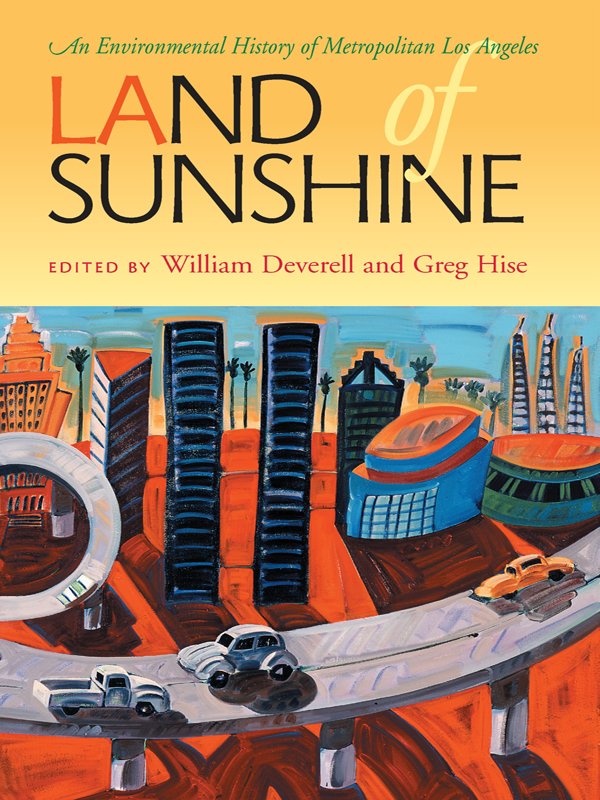

The idea for this book came from members of an advisory group at the University of Pittsburgh Press; we appreciate the press's commitment to publishing environmental history and the Senate Committee of the University Press's assessment that we ought to edit a volume on Southern California. Niels Aaboe, then editorial director, brought us on board and shepherded the project through its first iteration. Director Cynthia Miller ably oversaw the latter stages of editing, design, and production. Reports from two anonymous reviews helped us rethink the book's structure; their suggestions made a good book better. Both the press and we as editors thank the authors for their contributions and for their patience. By any measure, the value readers find in this volume is a testament to the quality of their scholarship and to the larger whole created through bringing individual studies together for a collective analysis of the region. We thank as well those authors who provided photographs and original art. Carolyn Cole (Los Angeles Public Library), Jim McPartlan (University of Southern California), Lisa Padilla (Zimmer Gunsul Frasca Partnership), Dace Taube (University of Southern California), and Jennifer Watts (Huntington Library) helped us secure artwork and permissions and format illustrations for publication. We think Frank Romero's Cityscape evokes the region's cultural landscape and are pleased he agreed to our request to reproduce it. Our thanks go to Patricia Correia and to Dean Dan Mazmanian (School of Policy, Planning and Development) for their assistance in securing the image and its use. John McPhee graciously allowed us to publish an excerpted version of Los Angeles Against the Mountains. Victoria Fox of Farrar, Straus and Giroux assisted us with permission and reprint rights. Ann Walston and Deborah Meade (University of Pittsburgh Press) and copy editor Trish Weisman did much of the work of turning a manuscript into a book.

A grant from the John Randolph Haynes and Dora Haynes Foundation allowed us to offer contributors a modest honorarium and to offset some costs for reproduction and permissions. As helpful, most likely more so, was the foundation's support for A Sustainable Future? Environmental Patterns and the Los Angeles Past, a symposium held at the California Institute of Technologyin September 2003. Each of us benefited from time away from our usual duties and the ideas generated through a community of scholars. Bill Deverell acknowledges the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences. Greg Hise thanks the Rutgers Center for Historical Analysis, conveners Susan Schrepfer and Phil Scranton, and participants in the center's Industrial Environments workshop (20012).

Introduction

The Metropolitan Nature of Los Angeles

GREG HISE AND WILLIAM DEVERELL

Whatever man has done subsequently to the climate and environment of Southern California, it remains one of the ecological wonders of the habitable world.

Reyner Banham, Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies

As we send this book to press, questions over the environmental sustainability of greater Los Angeles figure prominently in public and policy debates. In everyday conversation, talk about sustainability is shorthand for natural capital, environmental carrying capacities, and our ability to ensure that the needs of the present are met without compromising future generations. With this understanding, it is obvious that any assessment of sustainability must include temporal perspectives. In other words, history matters. It matters a great deal. Looking back, timelines of environmental stability and change must be carefully constructed and scrutinized to fashion appropriately sophisticated practices and policies supportive of sustainability. Looking ahead, the concept's moral and ethical principles also assert that what we do today matters for those who follow.

In an attempt to contribute to discussions of sustainability, Land of Sunshine explores the environmental history of greater Los Angeles. Rather than sketching out a past and tracing a chronological route to the present, the authors instead range widely across time and theme, speaking in sum across a large set of regional environmental factors, environmental perspectives, and environmental challenges. Accordingly, we have broken the book into threelargely thematic sections: analysis of place, land use and governance, and nature and culture.

Several threads run throughout. One concerns the regional particularities and problems of a utilitarian ethos regarding the environment, the continuing belief that nature works for us when we work nature. Another is the related idea, now several centuries old, that Southern California is a paradisiacal garden, to quote a nineteenth-century newspaper, the Los Angeles Star, awaiting only the shaping hands of human action and labor. In their respective investigations, several authors take up aridity and the control and use of water: interrelated processes of nature and culture that characterize (even caricature) much about the environmental history of the region. A few take up discrete environmental topicspollution, oil, the vegetative landscape, and planning, for examplewhile others work at larger scales of environmental change through imagery, text, or both. Some have produced deep histories of the region (the archeologist Mark Raab's analysis of the consequences of environmental change in precontact periods and ecologist Paula Schiffman's reconstruction of the Los Angeles prairie, for example). Each chapter stands alone as an investigation of altered landscapes and altered perceptions of environment over time in Los Angeles, and each contributes to a larger whole that concerns time, nature, and culture.

The concerted regional effort to harness nature in service of an earthly Eden in Southern California has required enterprise and given rise to technological innovation. Enterprise and innovation have in turn attracted capital and generated wealth. Contrary to most accounts, greater Los Angeles has been on the map of global trade for two centuries. Capitalism and international trade link ecosystems once discrete. Growth created and continues to create dynamics of environmental change: migrating people have brought plants and animals with them, and these organisms have transformed local ecologies and, as Unna Lassiter and Jennifer Wolch note in their chapter on the metropolitan presence of farm animals, local neighborhoods.