Copyright 2010 ditions Robert Laffont, Paris

Originally published in Spanish as Mi nombre es Victoria

by Editorial Sudamericana, S.A., 2009.

Translation copyright 2010 Magda Bogin

Foreword copyright 2009 Alberto Manguel

c/o Guillermo Schavelson & Asociados, Agencia Literaria,

www.schavelzon.com

Afterword copyright 2011 Pablo A. Pozzi

Production Editor: Yvonne E. Crdenas

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Other Press LLC, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. For information write to Other Press LLC, 2 Park Avenue, 24th Floor, New York, NY 10016.

Or visit our Web site: www.otherpress.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

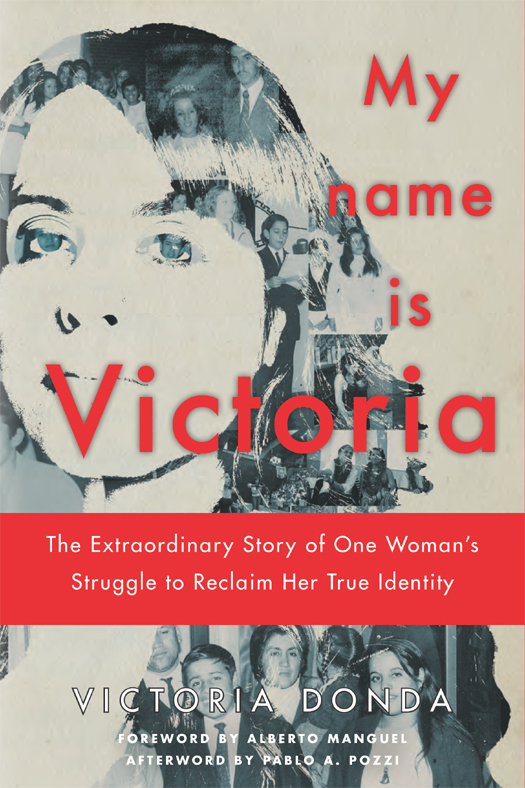

Donda, Victoria.

[Mi nombre es Victoria. English]

My name is Victoria : the extraordinary story of one womans struggle to

reclaim her true identity / by Victoria Donda ; translated by Magda Bogin ;

[foreword by Alberto Manguel ; afterword by Pablo A. Pozzi].

p. cm.

Originally published in Spanish as Mi nombre es Victoria by Editorial

Sudamericana, S.A., 2009.

eISBN: 978-1-59051-405-4 1. Donda, Victoria. 2. Children of disappeared personsArgentinaBiography. I. Bogin, Magda. II. Title.

HV6322.3.A7D6613 2010

362.87dc22

[B]

2010040657

v3.1

Contents

FOREWORD:

A CHRONICLE FROM HELL

by Alberto Manguel

AFTERWORD:

WE ARE ALL PERONISTS

by Pablo A. Pozzi

Foreword

A CHRONICLE FROM HELL

by Alberto Manguel

HISTORY

In the mid-1960s, hardly anyone in Argentina could have imagined that the following decade would be the bloodiest and most barbaric in the countrys history. In 1966, a military coup toppled President Arturo Umberto Illia and handed full dictatorial powers to General Juan Carlos Ongana. This ultra-conservative, antiliberal military man immediately placed all public universities under government control and disbanded all labor unions. In response to these abusive measures two popular movements were born: the ERP (Ejrcito Revolucionario del Pueblo, or Peoples Revolutionary Army), which was essentially Trotskyist, and the Montoneros, who considered themselves followers of the exiled former president Juan Domingo Pern. Their actions led to Onganas destitution and the designation of another general as head of state. In July 1973, new elections were held, as a result of which Pern, who had been living in Spain since 1955, was returned to the presidency with 60 percent of the vote. After Perns death only a year later, his widow, Mara Estela Martnez de Pern, known as Isabelita, succeeded him, but she quickly became a pawn in the hands of the army. On March 24, 1976, another coup dtat brought to power a triumvirate led by General Jorge Rafael Videla, who banned political parties and unions and imposed press censorship throughout the country. On the pretext of fulfilling permanent obligations, Videla and the members of his junta launched a campaign of repression such as the country had never seen before. Their objective was to destroy the insurrection, but their victims were not necessarily all on the left. Anyone who opposed their regime, even a friend, relative, or acquaintance of a dissident, or anyone who in any way, however slight, had annoyed a member of the military, was considered an enemy. A terrorist, Videla declared, is not just someone with a bomb or a gun, but any individual who spreads ideas that run counter to Western Christian civilization.

Videlas government introduced a semi-clandestine structure to enforce its will. Its war councils could impose the death penalty on anyone, for any crime. The junta set up detention centers and established special units composed of police officers and members of the three branches of the armed forces. Headed by regional commanders who obeyed only their superiors, their mission was to kidnap, torture, interrogate, and kill. This hermetically sealed organization was impervious to influence from the families of its victims and allowed the government to deny all responsibility for the abuses it committed. For almost ten years, members of the Argentine military tortured, reduced to slavery, and murdered tens of thousands of men and women of all ages and from every social background. Inside the military prisons, hundreds of babies were torn from their mothers and sold or given to sympathizers of the regime. One of those newborns was Victoria Donda.

In 1985, two years after the end of the dictatorship, a civil court sentenced Videla to life in prison; other military leaders received shorter terms. In 1990, President Carlos Menem pardoned them all, but that amnesty was overturned in 1998, when a new court sentenced Videla to ten years under house arrest for having been an accomplice in the theft of newborns. A few months before he was set free, in August 2009, a new civil court decreed that the former dictator should be tried again for the torture and murder of political prisoners in the province of Crdoba. Unfortunately, the Argentine legal system, by and large conservative and corrupt, did not issue clear, straightforward accusations with unappealable sentences that would have put a final stop to a past that was still alive. Spread out over time, the lenient and meager sentences handed down to those responsible for thousands of atrocious crimes left the Argentine people with the impression that a whole bloody decade had ended with a simple public scolding instead of with the sort of exemplary punishment that would have met the countrys moral yearning and served as a warning to future governments.

No human society is exempt from injustice. Over the course of centuries, history has inured us to the idea that the suffering of others, of our neighbors, or of strangers, is necessary in order to consolidate a nation, define its borders, and crown it in glory. One need only think of the Greek attack on Troy and the Roman genocide in Carthage. Like every other country on the planet, Argentina owes its existence to unspeakable horrors that are often forgotten. Under cover of our War of Independence and our conquest of the desert, we turned our cruelty against indigenous people and slaves, establishing from the moment we founded our first cities the principles of inequality and abuse of power. It doesnt surprise us that the hero of our national epic, Martn Fierro, should be a fugitive from the law and a deserter, since in Argentina both judges and soldiers represent a long tradition of infamy. As in so many countries, dictatorial regimes have made disobedience a heroic act for which few people are prepared.

The state of terror induced by dictatorships everywhere is always, in the last instance, a situation that takes people by surprise. During the years leading up to Nazism in Germany or Fascism in Italy, hardly anyone foresaw the scope of the criminal acts those regimes would commit. Even in countries where dictators are nothing new (as in Argentina, which suffered the bloody rule of Juan Manuel de Rosas in the nineteenth century), people always have a tendency to believe, in the peaceful interim, that such abominations could never happen again here or now. Despite the lessons of history, the states that consider themselves democratic (a claim almost always open to debate) expect to be immune to gross abuses of power. Yet theyre invariably mistaken. No country, not even one with a solid legal system, is safe from corruption and state violence. Under the pretext of protecting its citizens, of providing better governance so as to deliver better guidance, the power of a supposedly democratic state can quietly modify a law, suspend a right, institute censorship, and adopt repressive measures that will slowly but surely replace constitutional rules with a dictatorial regime. No country ever enjoys a true guarantee of safety. Every morning we run the risk of having our rights stolen in the afternoon, and every afternoon we risk losing them by the next morning. This is why the first obligation of every citizen is to stay vigilant and to reject any governmental transgression or abuse of power. And of course, we have a duty to bear witness.