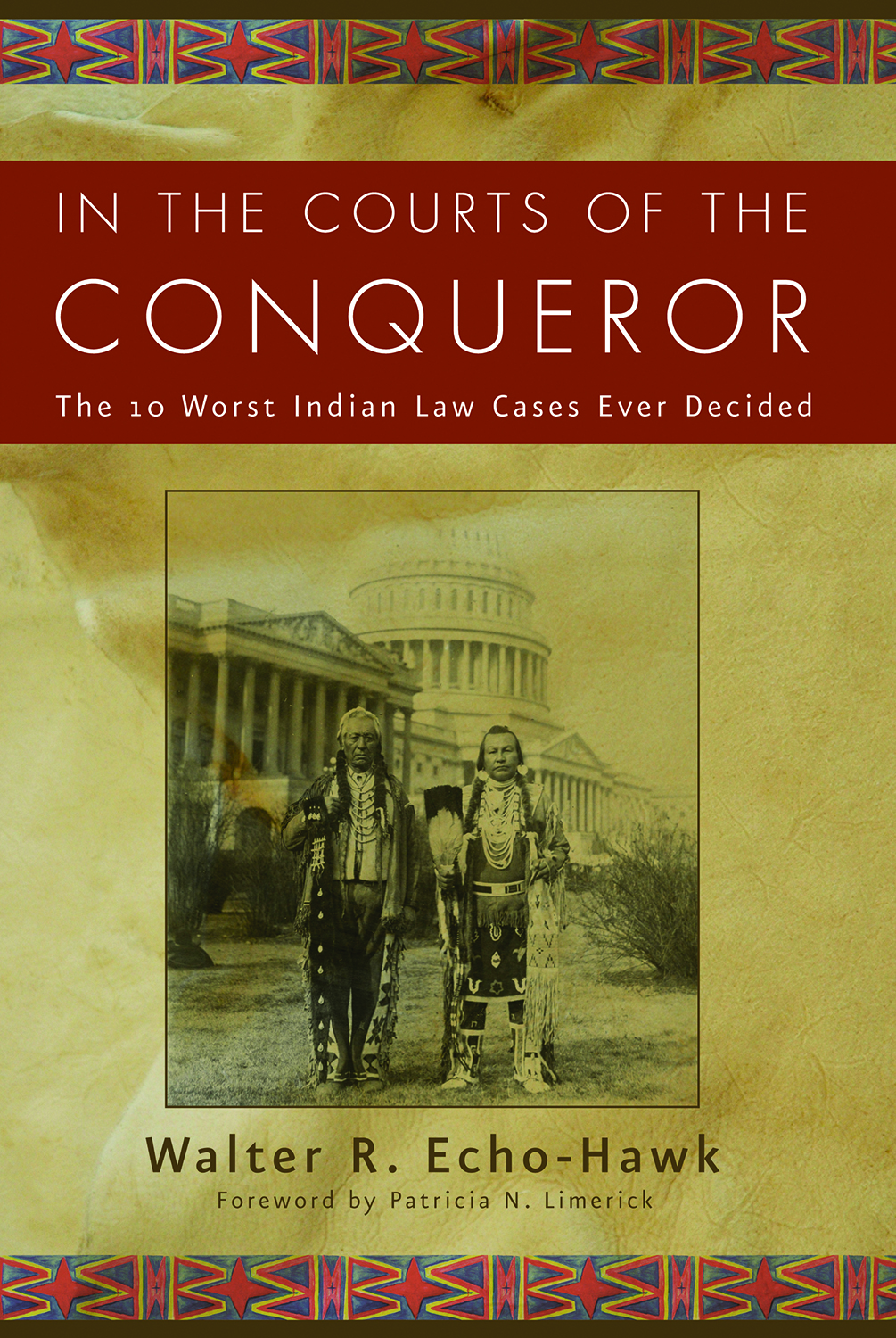

The 10 Worst Indian Law Cases Ever Decided

Walter R. Echo-Hawk

Chapter Four

Johnson v. MIntosh: How the Indians

Lost Legal Title to America

IN 1773, WILLIAM MURRAY bravely crossed the Allegheny Mountains carrying a forged British legal opinion into the forbidden zone set aside by the king for Indian tribes. The fraudulent document was altered to allow him to purchase Indian land, an act otherwise prohibited by the law of the redcoats. Once deep in the heart of Indian country, the sweaty-palmed agent handed the fake document to the local British commander, who fell for the trick. Thus, Murray was allowed to buy land, even though he and his wealthy backers knew it was illegal under British law. Thus begins the story of the spurious land claim in Johnson v. MIntosh , one of the ten worst Indian law cases ever decided.

Huraaru from the beginning, it was all about land. To the American Indian tribes, Mother Earth is the wellspring of indigenous culture, religion, and economic life. It forms the identity of Native Americans as indigenous peoples. Unlike Central and South America, where Native American civilizations adorned with gold and mountains made of silver lay available for the taking, Mother Earth was the principal asset in North America. Even before the first British ships landed on Virginia shores, the colonists wondered, Can we simply take the land, or do we have to buy it? The astounding discovery of the New World was one of the most important events in the history of mankind, and an equally remarkable legal doctrine was needed by the Europeans to reduce the land to their ownership and possession. The problem, of course, was the Indian tribes. By 1600, the British knew the continent was already fully inhabited, but did the Indians really own the land? That question was of paramount importance in founding the colonies because the dominant purpose of the whites in America, according to the United States Supreme Court, was to occupy the land.

Indeed, the very purpose of the colonists was to acquire the vast expanse of land that lay before them that was seemingly available for the taking; and the unrelenting greed for landIndian landbecame the driving engine for the expansion and settlement of the western frontiers by the American settlers after they won independence from Britain. In a remarkably short span, nearly the entire continent was transferred from indigenous to nonindigenous hands by various means. Was that massive, one-way transfer of land legal?

This chapter explores the legal foundation for land ownership in the United States. Plainly, a clear and very potent legal right was needed by the colonists to support their occupation of Indian territory and to obtain ownership of the land. Otherwise, their occupation must at its core be considered illegal and illegitimate.

To provide the setting for the Johnson case, we will first examine early legal theories for acquiring Indian land in British North America under the redcoats and then look at land speculation during colonial times and in the early days of the new republic until 1823, when Johnson was decided. Finally, I will tell the story of the Johnson case and its far-reaching impacts on American Indians.

It is amazing that over 750 law review articles and several books have been written about Johnson v. MIntosh in recent times, yet it was not until 2005 that the first complete story of this case was told. In 1991, a law professor named Lindsay G. Robertson made a startling find: a trunk containing the complete corporate records of the plaintiff land companies in that case. The records reveal a truly sordid tale of collusion by many of the leading figures of the day, surrounding a fraudulent purchase of an enormous tract of Indian land by wealthy land speculators. They sought to validate their illegal purchase through a friendly lawsuit about a feigned controversy that was conceived and prosecuted by crafty lawyersinfluence peddlers, reallyand this case was decided by a chief justice of the Supreme Court who possessed an enormous stake in the outcome. The opinion thus produced contained far-reaching dicta that gravely compromised Indian land rights in the United States, even though no Indian tribes were parties to the case. This entire affair occurred within the context of speculation in land owned and occupied by Indian tribes.

The serious irregularities in this litigation brought to light by Robertson gravely impugn the legitimacy of the Johnson decision and should leave many to wonder whether the decision is entitled to receive continuing effect by the courts. Yet at this writing, Johnson does remain a landmark decision in the United States and several other settler states that restrict indigenous land rights. It provides the foundation for modern land ownership in those nations.

Early Theories for Obtaining Land Occupied by Indian Tribes

In the beginning, the Pilgrims and Puritans debated several theories to justify occupation and acquisition of land inhabited by Indians. The most optimistic viewpoint was that the land was not owned by anyone and was simply available for the taking. After all, the British royal charters clearly empowered the newcomers to settle and occupy any non-Christian lands and establish colonies, didnt they? As law professor Stuart Banner observes, the charters granted property rights as if the colonists were to be the first human beings in the area. This fiction was bolstered by the false notions that the Indians themselves had no concept of property, did not claim any property rights, or were otherwise seen by the newcomers as incapable of owning land. Indians did not have any laws, they argued, and were nomads who did not stay in one place long enough, it seemed, to acquire property rights in land. However, once the settlers were confronted by powerful Indian tribes, the belief that no one owned the land quickly evaporated and nagging doubts arose whether their settlement on Indian land was actually legal. Furthermore, any notion of unowned land was complete nonsense, according to Banner, since the English found a pre-existing system of property rights everywhere they went.

Even if Indian land ownership was conceded, some colonists and colonies took the land under other theories. Foremost among them was the religious justification argumentthat Christians have a right to take land from non-Christians. Since colonization brings Christianity to heathens, so the argument went, surely this benefit is payment enough for taking Indian land. After all, we cannot Christianize the Indians unless we can settle nearby on their lands. This supposed right to simply take non-Christian land turned also upon the Eurocentric legal fiction that heathens lack property rights. At bottom, however, the religious justification of the English, like that of the Spanish, was largely a pretext. The colonization of the Americas had little to do with Christianity, and as time went along the pretext was abandoned. As the English settled more of North America, the religious justification for acquiring land virtually disappeared, according to Banner, and the supposed right of Christians to take non-Christian land is scarcely found after the early seventeenth century.