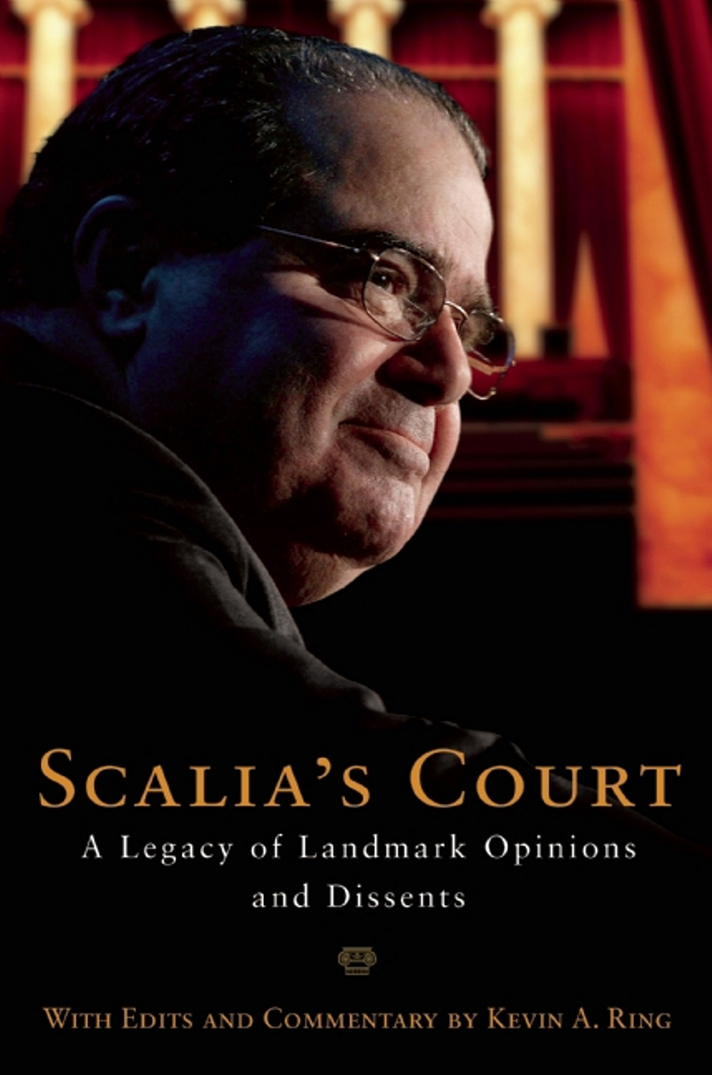

Copyright 2004, 2016 by Kevin A. Ring

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, website, or broadcast.

Regnery is a registered trademark of Salem Communications Holding Corporation

Portions of this book were originally published in 2004 under the title Scalia Dissents: Writings of the Supreme Courts Wittiest, Most Outspoken Justice (ISBN 978-0-89526-053-6)

First e-book edition 2016: ISBN 978-1-62157-533-7

Cataloging-in-Publication Data on file with the Library of Congress

Published in the United States by

Regnery Publishing

A Division of Salem Media Group

300 New Jersey Ave NW

Washington, DC 20001

www.Regnery.com

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Books are available in quantity for promotional or premium use. For information on discounts and terms, please visit our website: www.Regnery.com.

Distributed to the trade by

Perseus Distribution

250 West 57th Street

New York, NY 10107

FOR KILEY AND AUDREY

Table of Contents

Guide

CONTENTS

S HORTLY AFTER THE PRESS reported Supreme Court Associate Justice Antonin Scalias death on February 13, 2016, tributes began pouring in from longtime allies and adversaries alike. Many noted his towering intellect and praised his consistent approach to interpreting cases. Some spoke of his love of the law and his larger-than-life personality. Others were impressed that his strongly held views did not prevent him from establishing warm friendships with those who disagreed with him.

One trait that nearly everyone praised was Scalias brilliant literary style. His gift for analysis and words, one progressive law professor said, made him the best judicial stylist since Oliver Wendell Holmes. Through his opinions, he exerted gravitational pull on the law, even when he lost. Indeed, during his nearly thirty years on the Court, Scalia was its premier conservative, intellectual gladiator, and wordsmith.

To be sure, many important and influential conservative jurists have served on the High Court, and there remain today others who share Scalias textualist and originalist philosophy. Yet it was Scalia who gave life to Aristotles injunction that it is not enough to know what to sayone must know how to say it.

His words could be pointed. Todays opinion has no foundation in American constitutional law, and barely pretends to, he charged in one case.

Scalias opinions could also be remarkably witty and humorous. Explaining why he did not think the Court should try to create a standard for defining literary or artistic value in an obscenity case, Scalia said,... in my view it is quite impossible to come to an objective assessment of (at least) literary or artistic value, there being many accomplished people who found literature in Dada and art in the replication of a soup can.

His humor was often subtle. Consider his explanation of the proper meaning of the term, modify. Modify, in our view, connotes moderate change. It might be good English to say that the French Revolution modified the status of the French nobilitybut only because there is a figure of speech called understatement and a literary device known as sarcasm.

Scalia could conjure up vivid images to communicate his arguments. In one case, rather than simply admonish the Court for its selective use of the often criticized Lemon test, which was created to identify government action that violates the religious Establishment Clause (see

Decrying the Courts refusal to reconsider its controversial decision in Roe v. Wade despite agreement among the majority of the Court that the decision was flawed, Scalia said, It thus appears the mansion of constitutionalized abortion law, constructed overnight in Roe v. Wade, must be disassembled doorjamb by doorjamb, and never entirely brought down, no matter how wrong it might be.

In addition, Scalia had a special ability to put complex arguments about fundamental principles in easy-to-understand terms. Slicing through the various First Amendment analyses that might be applied to determine the speech rights of the religious, Scalia concluded, A priest has as much liberty to proselytize as a patriot.

As even casual followers of the Supreme Court recognized, Scalias words could reveal his outrage at the decisions reached and lack of judicial restraint demonstrated by his colleagues on the High Court. Scalia concluded one opinion, The Court must be living in another world. Day by day, case by case, it is busy designing a Constitution for a country I do not recognize.

Finally, Scalia could use language to humanize his argument, to let the reader inside his life and mind, a frequently useful step toward persuasion. Some there aremany, perhapswho are offended by public displays of religion, Scalia wrote in a 2014 opinion. Religion, they believe, is a personal matter; if it must be given external manifestation, that should not occur in public places where others may be offended. I can understand that attitude: It parallels my own toward the playing in public of rock music or Stravinsky. And I too am especially annoyed when the intrusion upon my inner peace occurs while I am part of a captive audience, as on a municipal bus or in the waiting room of a public agency. Scalias portrait of a Supreme Court Justice stuck at the DMV is not what one expects to find in a judicial opinion.

Scalias way with words is what makes this book possible. His opinionsthough full of legal arguments and analyses only a lawyer could loveemploy metaphors, stories, and emotion in ways that frequently carry legal writing into the realm of belles-lettres. His entertaining writing style made it easier to understand and remember his arguments. It made some of the most mundane areas of the law seem interesting.

The opinions chosen for this book are not necessarily Scalias most important but those that I believe are the most interesting to read. Most are dissenting opinions, in which Scalia was not burdened by having to speak for others and in which his passionate views could be set forth with all the fury and righteousness he could muster. His abortion dissent in Casey (chapter five) burns on the page. Other opinions, like his majority for the Court in Heller (chapter six), upholding an individual right to bear arms, demonstrate his method of interpretation.

Together, the opinions in this collection show Scalias judicial philosophy in practice, reveal his skill at argumentation, demonstrate his ability to foresee future controversies, and showcase his compelling writing style. In every opinion, a combination of these factors is at work. Before each opinion, I provide information to give the reader background on the case: the relevant text of the Constitution, its historical interpretation, Scalias general view of the text, the Courts previous decisions in the area, the relevant facts that led to the case, and the opinions of the Court and other Justices.