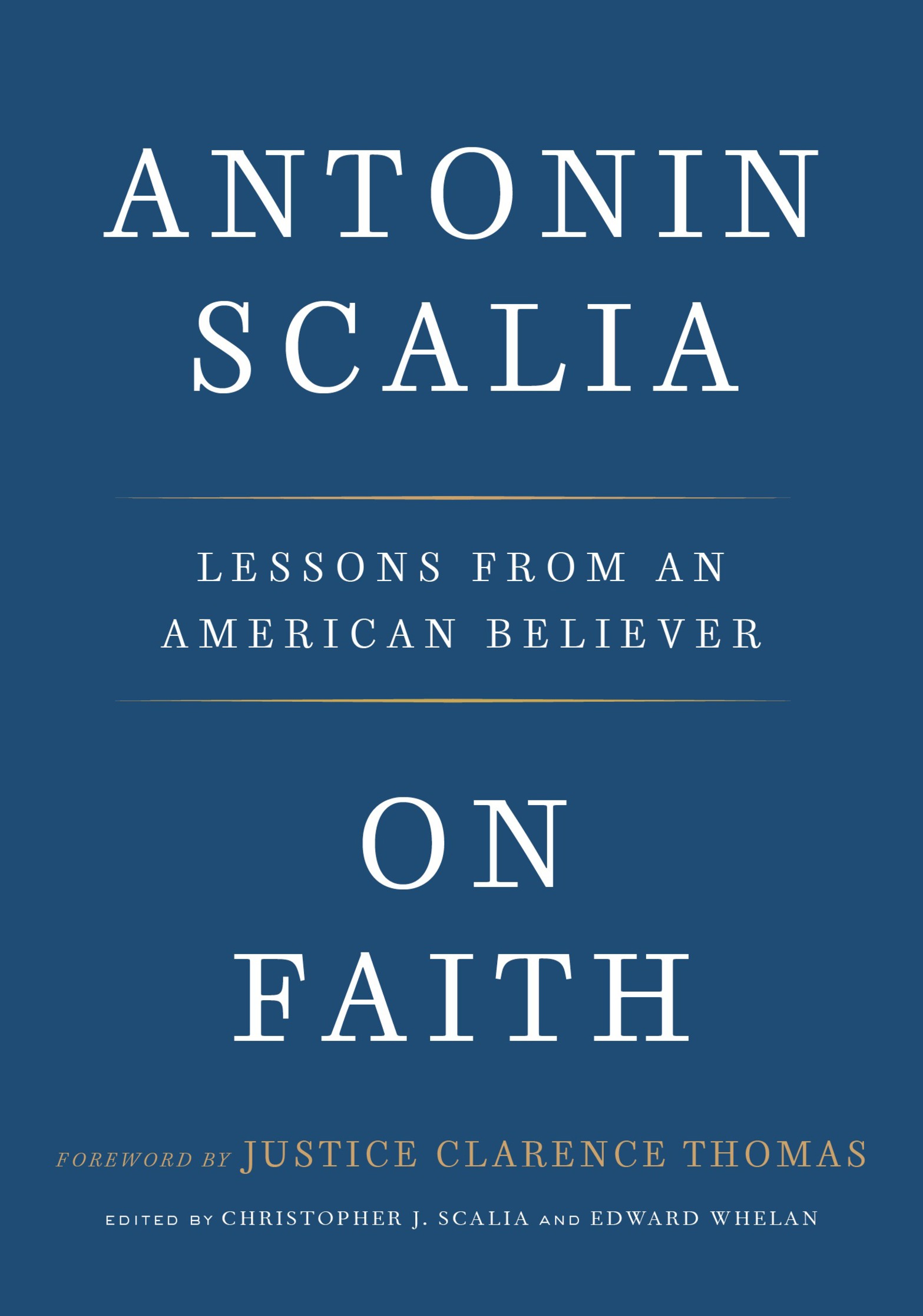

As the double meaning of the subtitle suggests, this volume collects Justice Scalias thoughts both about religious belief and about the place of religion in American public life. It comprises some of his many efforts, as a faithful Catholic and proud American, to inspire and guide others in their faith and citizenship, and to explain the freedoms that the Constitution grants, as well as the limitations it places, on religious expression. The collection includes speeches, excerpts from some of his Supreme Court opinions, and reflections on his faith by his friends, colleagues, law clerks, and family.

For ease of reading, we have sometimes omitted internal citations and ellipses and have occasionally changed capitalization and punctuation, but we have often retained Justice Scalias distinctive use of commas and semicolons.

With one exception, all of the personal reflections are published here for the first time.

Justice Scalia had done preliminary work on a collection of his religious speeches before his untimely death. It is our honor to have expanded and completed his project; it is our hope that this book gives you a deeper appreciation of his faith in God and his love for his country.

FOREWORD

BY JUSTICE CLARENCE THOMAS

I was truly blessed to have had Nino at the Court when I became a member. And I was blessed many times over the almost twenty-five years that we served together.

There were countless chats walking to chambers after oral arguments or after our conferences. Those very brief visits usually involved more laughter than anything else. There were the many buck-each-other-up visits or checking on each other after one of us had an unpleasant experience. And there were calls to test an idea or work through a problem.

Nino worked hard to get things rightthe broad principles and the details of law, grammar, syntax, and vocabulary. He was passionate about it all; all deserved and received his full attention. I loved the eagerness and satisfaction in his voice when he finished a writing with which he was particularly pleased. Clarence, you have got to hear this. It is really good. Whereupon he would deliver a dramatic reading.

For the last few years of his life, my place on the bench was between Nino and Steve Breyer. I loved the back-and-forth that took place, especially the passing of notes and the whispered or muttered commentary. When Nino wanted to talk quietly with me about something, he would lean far back in his chair and say in an almost endearing tone, Brother Clarence, what do you think?

Nino did not discuss his faith with me often, but his deep belief in God was implicit in everything he did.

In todays world, its easy to mouth platitudes about ones faith without taking corresponding actions. I dont recall Nino ever doing so. He made it clear that practicing his faith was important, but never in a trite way. If anything, I would occasionally hear him chide himself for not attending daily Mass and praise his wife, Maureen, for doing so. But he was not showy or flamboyant about his faith. For Nino, it was what he did and how he did ithis dedication both to his vocation as a judge and to his beloved familythat spoke loudly for him.

Ninos faith was robust, deeply personal, and central to his lifeit guided him and gave structure to his life. It led him to love and care well for his family. And it fueled a deep commitment to his judicial oath and the duties and obligations that it entailed. This is what I saw on a day-to-day basis. His Catholic faith helped him to understand that he had no right or license to exceed his judicial authority or to abdicate his responsibilities; it imposed a constant judicial modesty or humility. He would be violating his oath if he imposed his personal views on others under the guise of a judicial opinion, and he had no inherent or personal right to judge his fellow man. Rather, his only authority was his limited role as an Article III judge, and he had given his word to Almighty God to comport himself consistent with this limited grant of authority.

One need only read his opinions to see this discipline and restraint. The effort that he put into each opinion was not for personal vanity or aggrandizement. It was not for manufacturing a legacy. Rather, it was because his oath, which rested on the foundations of his faith, required him to give his all.

Likewise, he would also violate his oath if he withheld a legitimate judicial opinion that might upset otherseven those he loved. He was required to do his absolute best in each case, to be honest with himself and with others, no matter how difficult, no matter if it led to disagreements. In the end, God was watching and would be the final Judge, and it was to Him alone that he would give an account. To the very end, upholding his oath is precisely what he did.

When our work was particularly challenging and the burdens seemed oppressive, I would occasionally drop in to visit him in his office. In short order, it was always clear that he would soldier onhis faith and commitment to God required that he do so.

In a sense, it was providential (and certainly not probable) that we would serve together. When I joined the Court, I only knew of him but had never met him. He was from the Northeast, while I am from the Southeast. He came from a house of educators, I from a household of almost no formal education. But we shared our Catholic faith and our Jesuit education as well as our sense of vocation. Our faith mattered, and so it was that our work had to matter and had to be done right.