CANNABIS

Reaktions Botanical series is the first of its kind, integrating horticultural and botanical writing with a broader account of the cultural and social impact of trees, plants and flowers.

Published

Apple Marcia Reiss

Bamboo Susanne Lucas

Cannabis Chris Duvall

Geranium Kasia Boddy

Grasses Stephen A. Harris

Lily Marcia Reiss

Oak Peter Young

Pine Laura Mason

Willow Alison Syme

Yew Fred Hageneder

CANNABIS

Chris Duvall

REAKTION BOOKS

Published by

REAKTION BOOKS LTD

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC1V 0DX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2014

Copyright Chris Duvall 2014

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China by 1010 Printing International Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780233864

Contents

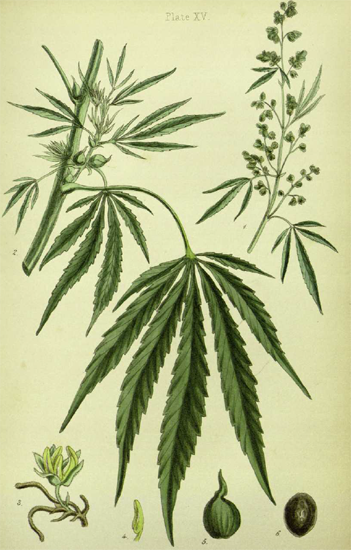

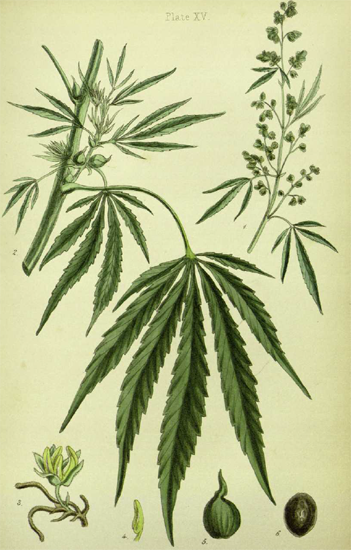

Cannabis sativa, from Edward Hamilton, Flora Homeopathica (1852).

Preface

C annabis grows on all inhabited landmasses to about 60 degrees latitude, a distribution broader than any other crop. This book is my attempt at understanding how Cannabis gained its cosmopolitan status.

Cannabis has been a fellow traveller of human migrations from Palaeolithic Central Asia to the present. The humanCannabis relationship is complicated, and challenging to present in a historical narrative. To outline this relationship I have employed a geographically broad-scale analysis of a multidisciplinary range of sources. This book, like any world history of Cannabis, must omit many aspects of the plants past. One notable focus is the important, but generally overlooked, roles Africans and African-descent peoples have had in Cannabis history. Additionally, I find the United States significant for understanding current events, because it is a global centre of efforts to sustain Cannabis prohibition, and efforts to end it. Beyond these justifications is the reality that I live in the U.S., and my professional experience is in the field of African Studies. All Cannabis histories bear particular perspectives.

There are many world histories of Cannabis. In this book I am regularly critical of these works, which I believe are too generally founded on opinions, explicit or implicit, about whether the plant is good or bad. Instead, my starting point is that Cannabis has sharedpleasant to unpleasant interactions with very many people, and that we must recognize the diversity of these interactions before judging it (if such judgement is necessary). My hope is that this book will move beyond the goodbad polarity, and enable more informed management of the worlds most widespread crop.

one

What is Cannabis?

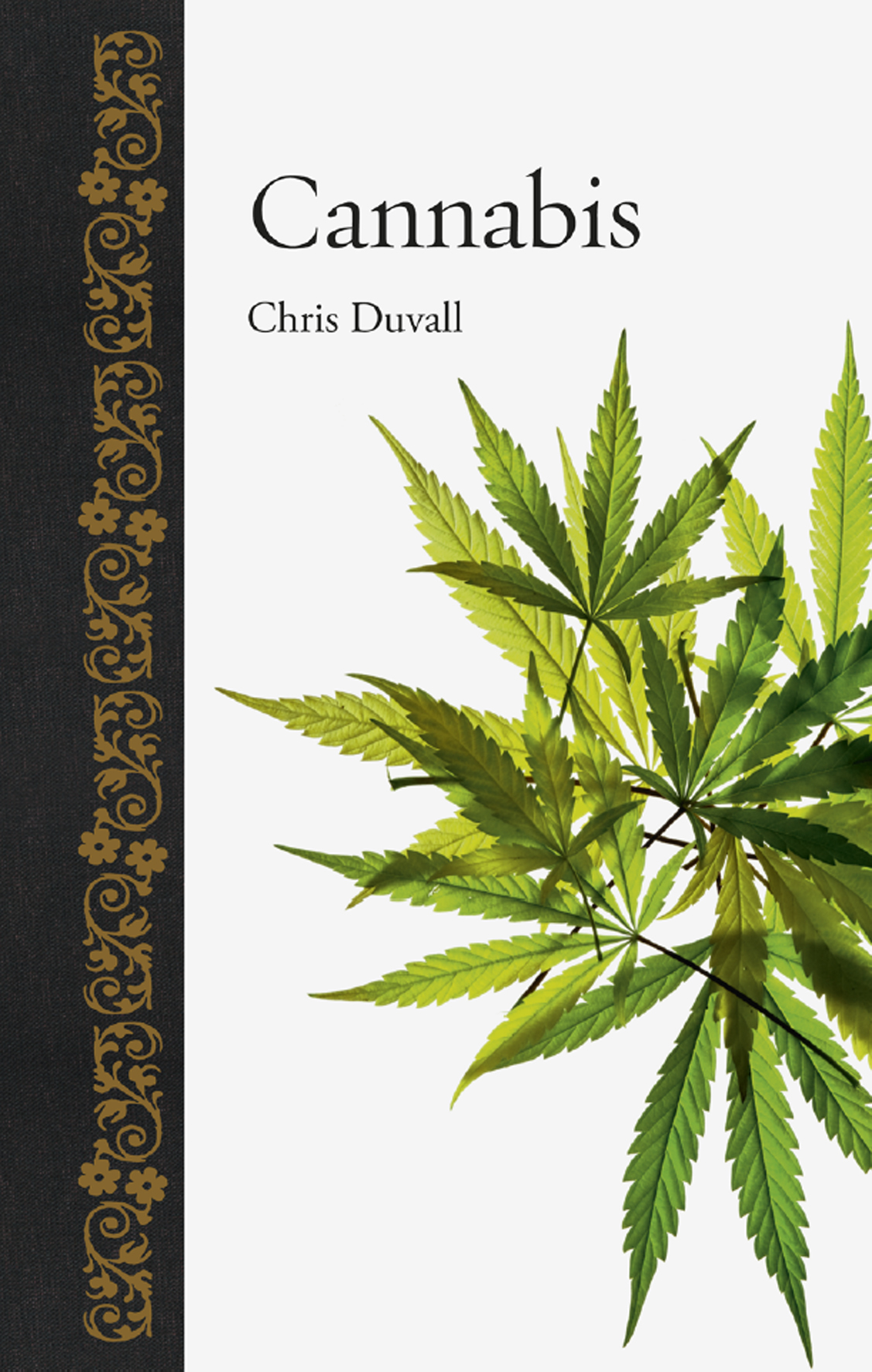

T he title of this chapter is a deceptively simple question. At first glance, perhaps, the books cover provides the answer it shows a plant leaf that many people immediately identify as marijuana, a widely used drug. Few plants have such an iconic leaf. The Cannabis leaf is effective visual shorthand, whether scrawled as graffiti or illustrating the cover of the Wall Street Journal (as on 20 April 2012). Many who see the leaf in this book will know they are reading about marijuana.

Yet Cannabis is not just marijuana. It is a plant that furnishes numerous products, not just drugs. The variety of its uses has for centuries fascinated many people, who have generated a massive literature on the plant. The book you are reading holds few of the millions of pages, paper and digital, published on Cannabis. Yet the immensity of this literature is misleading. As others have recognized, the literature has been unsatisfying for decades, littered with errors, received wisdom and narrow-minded judgements. It is vital to ask What is Cannabis? to make sense of the jumbled portrayal of the plant in current global society.

To understand Cannabis means working through layers of complication, beginning with language. Cannabis terminology is confused and confusing. In English, cannabis, Cannabis, hemp and marijuana are sometimes synonyms, but at other times differentiate botanical species, legal and illegal substances, good and bad uses of the plant, or even specific parts of the plant. These four terms also intermingle with esoteric vocabulary, whether English slang, standard and slang terms from other languages, formal scientific binomials or antiquated forms of any of these. Furthermore, meanings of Cannabis terms have varied over time and space. Equivalent terms in other languages are similarly confusing. Poor translations have compounded miscommunication for millennia.

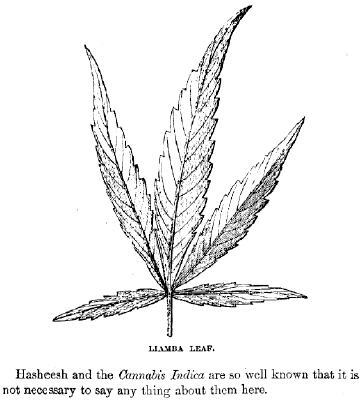

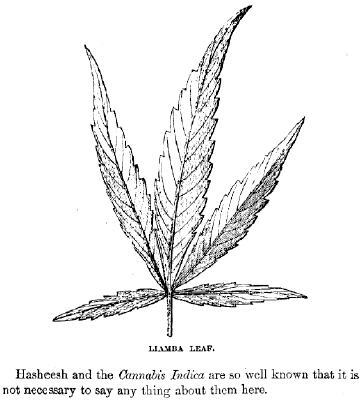

Paul du Chaillu, Explorations and Adventures in Equatorial Africa (1861). He overstated what was known about the plant.

The terms Cannabis and cannabis are fairly easy to define. When capitalized and italicized, Cannabis refers to a plant genus in the formal language of scientific taxonomy. In this scientific sense, the term has a history that predates the current, standard system Cannabis achenes are famous as hempseeds, which can provide food, oil, medicine and feed. Cannabis laticifers produce sticky resin that famously transports psychoactive phytochemicals.

Cannabis is now considered prototypical of a distinct botanical family, the Cannabaceae. This family was first proposed in 1820 by a Russian botanist,

Marijuana inflorescence with resin.

Tiny anatomical characteristics are important in scientific taxonomy, but for most people chemistry distinguishes Cannabis. All individuals in this genus produce phytochemicals called cannabinoids. The most famous is the psychoactive compound 9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), but there are at least 60 others, many of which have known, non-psychoactive pharmacological effects.

How does Cannabis differ from cannabis? When uncapitalized and unitalicized, cannabis refers to a plant genus understood informally outside scientific taxonomy. All cultures classify and name plants according to subjective naming rules and concepts of what makes different plants different, and base decisions about plant use on these so-called folk taxonomies.

Nonetheless, scientific taxonomy is one of many knowledge cultures relevant for understanding human