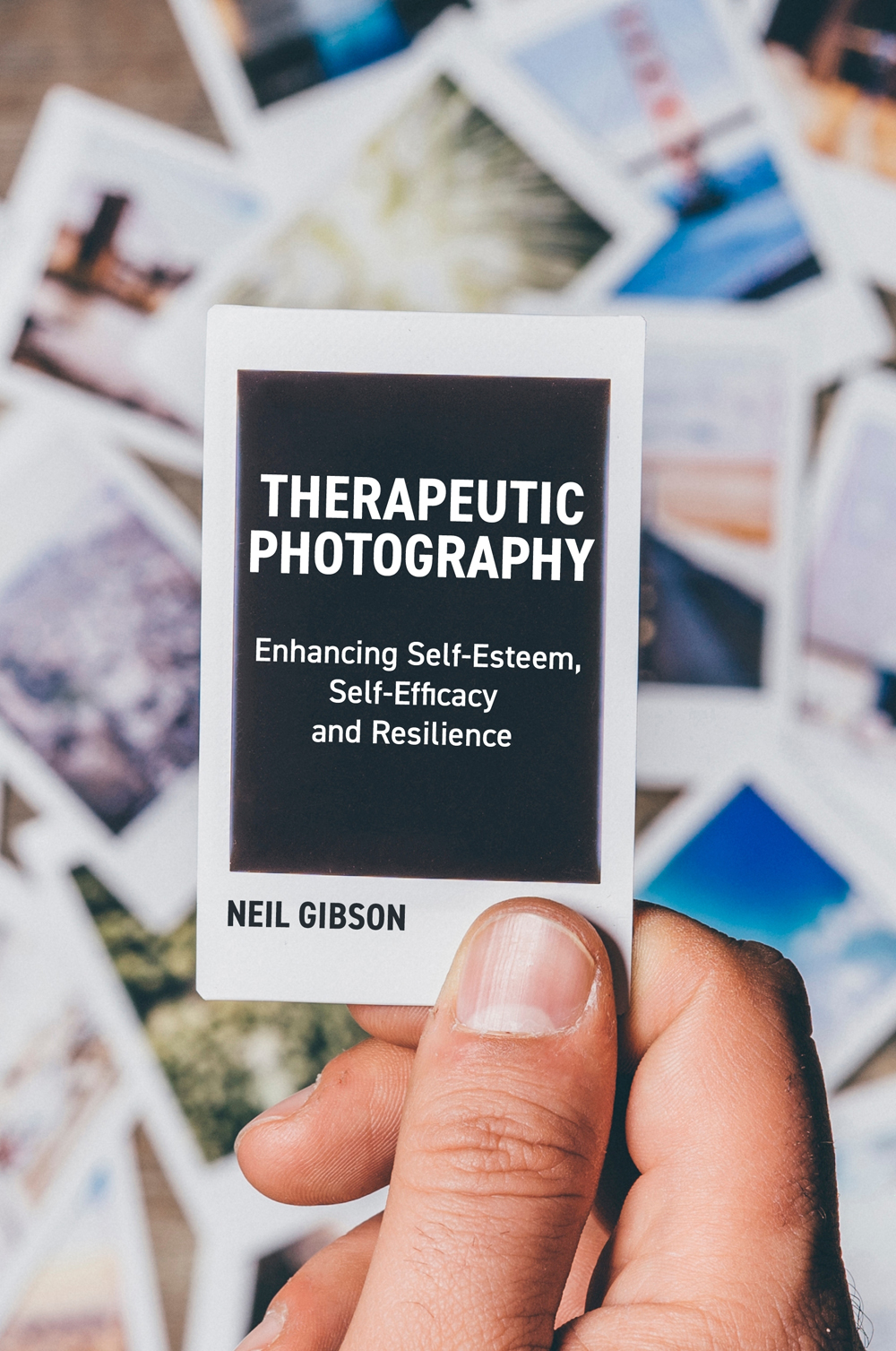

THERAPEUTIC

PHOTOGRAPHY

Enhancing Self-Esteem,

Self-Efficacy

and Resilience

NEIL GIBSON

Jessica Kingsley Publishers

London and Philadelphia

Contents

INTRODUCTION

Photographs and photography can be a powerful tool. A photographer aims the camera at a certain subject, presses the shutter at a certain time, and immortalises a scene frozen in time for all to see. The photograph is then printed, possibly after editing in a darkroom or on a software package, and then revealed to interested onlookers for a message to be conveyed and interpreted. The image can be passed around, reproduced in many formats, and may facilitate discussion and comment. The power behind the final image is rooted in numerous steps preceding the finished product, but can this power be therapeutic?

In 2004, I visited a refugee centre in Belgium for three months. During my time there I wanted to work with a group of asylum seekers and run a project with them. I had with me an old Nikon F100n film camera and several spools of 35mm black and white film, so I decided to run a photography club in the centre and asked volunteers to meet me one afternoon.

A variety of participants with different cultural backgrounds attended and I explained the purpose of the group to have fun with the camera, to take pictures of life in the centre, and to select images for display within the centre. Each day the participants would book out the camera and document their lives.

When I developed the images I expected to see a multitude of bleak, stark photographs of the cramped conditions, the unsanitary dormitories, and the oppressive atmosphere, but instead there were lots of smiling people. The participants spoke about the images and identified positives in their environment, which included a sense of community (albeit temporary), and the support they gleaned from one another. The images were displayed during a community open day and the participants wrote captions for each one explaining why they had captured that particular image.

Years later, the intervention still sticks in my mind. This was my first foray into using photography with clients, and my last for over ten years. From my practice experience I noted that within statutory UK services the work tended to be procedural and system driven. There seemed to be little opportunity to allow clients to creatively express and explore their situations, and the dominant method when working in adult services was the one-to-one interview, which relied solely on verbal information.

However, I did encounter pockets of practice where photography was being used: a day-care service for adults with a learning disability had set up a photography group; a young female in residential care was able to express emotions through photographs of seascapes in various weather conditions she had pinned to her bedroom wall; and care managers were engaging with photograph albums when conducting assessments. When I asked practitioners why they used photography there appeared to be no definitive reason, only that it seemed to be effective in engaging the client.

And so this was the starting point for my interest in therapeutic photography. I wanted to find out if photography could assist the caring professions, and initial research led me to the practice of therapeutic photography which appeared to underpin the pockets of practice I had encountered. Since then I have been involved in the design and delivery of therapeutic photography programmes with a wide variety of clients, including those with substance use issues, carers, people with mental health issues, young adults with employability issues, and adults with autism. This led to the writing of a PhD entitled Is there a role for therapeutic photography in social work with groups? from which material has been used to write this book. The programme has also been adopted by a number of organisations and incorporated into practice.

This book brings together the theorists who underpin the approach, the theories to assist in understanding the dynamics, and the practicalities of delivering therapeutic photography interventions. Included in the Appendix is the full programme, which was designed to be delivered over a six-week period, but it is anticipated that the reader can use this as guidance for initiating their own projects to adapt and design appropriate therapeutic photography approaches to use with their own clients.

Whats in the book?

In , the concept of therapeutic photography is introduced and explanation offered as to how it can be used. In doing this, the practice of phototherapy will also be discussed, drawing parallels and distinctions between the two approaches. The intended outcomes of using therapeutic photography as an intervention will also be explored within this opening chapter.

moves on to look at how therapeutic photography can actually be used in professional settings, drawing on the previous application of the approach within the field of research. Concepts of control and power dynamics between the facilitator and participant are introduced and the chapter examines who can benefit from this creative approach. Focus is given to the concept of identity and a three-stage model of exploration is suggested as a result of using therapeutic photography.

looks at the dynamics of using therapeutic photography and discusses the advantages of the approach, as well as the challenges, which include ethical and legal considerations. Within the chapter, the structure of delivery is analysed and ways in which a facilitator can focus attention on specific areas of concern are presented. This uses a systems-based approach, as originally proposed by Bronfenbrenner (1986, 1992, 2009), and uses the structure of his micro-, meso-, exo- and macrosystems to consider where pressures may be presented in the lives of participants.

In , the focus is on using therapeutic photography to explore the self. This includes consideration of self-portraiture, selfies, and other ways of creatively representing the self. It is often a useful starting point in any therapeutic intervention to ascertain how a person perceives themselves and this chapter recognises this, exploring issues of self-concept and self-esteem. Within this chapter, the reader is also introduced to some key psychoanalytic and psychodynamic theorists who aid in the understanding of the self and how perception may manifest through conversation, and through the photographs.

Humans are social beings and do not function in isolation, and images as a catalyst for conversation about the dynamics within the family, or it may involve the exploration of new images that creatively represent issues or people within family units. The reader is introduced to object relations theory and how this may be used to understand how participants or clients internalise past experiences and use these to shape expectations of relationships.

There is recognition when using therapeutic photography that it is not always easy or possible to photograph certain concepts that relate to issues in the lives of clients. identifies this and discusses ways in which participants can be encouraged to creatively represent things they wish to focus on. In order to do this, attachment theory is introduced as it offers further guidance about how to understand and interpret relationships, both within and outwith the family unit. This is linked to working with emotions, and ways in which clients can pictorially explore emotions are introduced.

When clients are in a professional setting, the concept of loss and change is often dominant as a person has to deal with a significant alteration in their circumstances. looks at the theory behind loss and change and how issues might manifest within photographs. There is also discussion of how a person may cope with transitions, and how photographic memories may be a source of comfort and support, but equally may prevent someone from taking steps to embrace change.

Next page