CONTENTS

About the Book

India is one of the worlds oldest civilisations, the birthplace of four major world religions and the origin of many of the ideas, philosophies and movements that have shaped the destiny of mankind.

In the twenty-first century, India is the largest democracy in the world, and is experiencing economic development matched only by its booming population.

It is only a matter of time before India becomes a world superpower.

Exploring the changing face of contemporary India, this revealing guide examines the nation in all its guises - as a liberal democracy where politics is shaped by highly conservative religious ideas, and as a global hub for technology and research, which is also home to 40 per cent of the worlds malnourished children. Getting to the heart of the countrys contradictions, this is an absorbing introduction to one of the most rapidly-developing countries in the world and reveals a future in which India will affect us all.

About the Author

John Farndon is the author of many books on international affairs, including several books in The Economist Business Travellers Guide series and books on subjects ranging from bird flu to Iran.

INTRODUCTION

India is a rising economic influence of power in the international system. Its a great multiethnic democracy.

Condoleezza Rice, US Secretary of State

Today, there is a great willingness internationally to work with India and to build relationships of mutual benefit.

Dr Manmohan Singh, Prime Minister of India

It is easy to think of the Bush administration of the USA as being doggedly gung-ho in its foreign policy and perpetually worried about any Asian power getting a little above itself. Yet in March 2005, Washington began to make the most extraordinary overtures to India, and announced that it planned to help India become a major world power in the twenty-first century not that most Indians would consider they needed help, of course, but the point was clear.

Later that year, Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh was feted in a visit to Washington, in which he was saluted with an almost unprecedented nineteen-gun salute. The following spring George Bush paid a cordial high-profile return visit to India. In dramatic contrast to his condemnation of Irans nuclear programme, Bush offered not just vocal but practical support to Indias nuclear aspirations though with caveats that might yet cause ructions.

To get some idea of just what a remarkable shift in attitudes this was, you only have to read of the Nixon governments attitude to India thirty years earlier, revealed, ironically, that same year in 2005, when US National Security Archives were finally opened. What the Indians need, Richard Nixon had shockingly commented, is a mass famine. Theyre such bastards, said Henry Kissinger, describing Indira Gandhi as a bitch. Kissinger had even urged the Chinese to invade India. Even the more open-minded Clinton administration had treated India somewhat warily. So Bushs open embrace was a sea change indeed.

In truth, this was not a sudden flash of enlightenment in American thinking, but simply an acknowledgement of something that has become glaringly obvious over recent years. Indias star is rising. Its economy is booming. Its population is swelling. And it has developed into a mature democracy; the worlds largest by far. If India has not yet actually arrived as a major force in the world, it seems that it will only be a matter of time before it does.

India rising

For the last three years, Indias economy has been swelling at well over 8 per cent annually and has now topped a trillion dollars. It is already the worlds seventh largest economy, and is likely to become one of the top three over the next twenty years. And it may soon become the worlds second largest consumer market, with a rising middle class over half a billion strong.

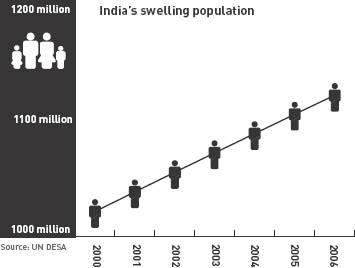

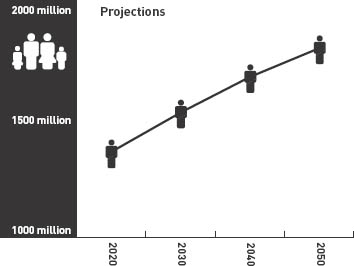

At the same time, Indians are beginning to make an impact on the world through sheer weight of numbers. Indias population, already 1.1 billion, is poised to overtake even China to make it the most populous country in the world. By 2030, it could be home to a staggering 1.6 billion people, compared to Chinas scanty 1.4 billion. And Indians are not just numerous at home. After China, India has the second largest diaspora of any nation, and there are Indians making an impact in almost every country in the world.

So whether the rest of the world wants to or not, it is going to have to interact with Indians in the near future and acknowledge the subcontinents massive presence. Many people in the West are already beginning to feel the India effect, as their jobs are outsourced to India, and queries about everything from their phone bills to after-sales service are answered from call centres in places like Mumbai and Bangalore. Over 40 per cent of major multinationals are now getting their backroom work done in India, where there are more graduates than the entire population of France, and where they come cheap (and ambitious). Meanwhile, major European and American corporations are facing not just competition from Indian rivals, but even hostile takeovers.

What is India?

Not surprisingly, people in the West are becoming increasingly interested in finding out what makes the new India tick, and there has been a whole spate of books, articles and documentaries examining the idea of India. Views differ, of course, yet the one thing they all agree on is that India is contradictory, enigmatic and just plain hard to pin down.

Source: P.N. Mari Bhat, Indian Demographic Scenarion 2025, Institute of Economic Growth, New Delhi, Discussion Paper No. 27/2001

There is a whole raft of superficial contradictions. India has been a fully fledged nuclear power since 1998, but it is also home to 40 per cent of all the worlds malnourished children. It combines a booming retail economy with, apparently, an enduring anti-materialist philosophy. It is one of the leading Asian players in the space race, yet it is dominated by ancient spirituality. It is at the forefront of some of the worlds cutting-edge technology and research, yet also home to some of the worlds most conservative, intolerant religious ideas.

Spice world

But the contradictions go deeper than this. In the past, westerners have viewed India through spice- or even dirt-tinted glasses, part of what Edward Said called the Wests Orientalism, which saw India as other. On the one hand, westerners saw India as exotic and romantic. The French novelist Andr Malraux wrote, Remote from ourselves in dream and time, India belongs to the Ancient Orient of our soul. Mark Twain was even more flowery, This is indeed India! The land of dreams and romance, of fabulous wealth and fabulous poverty genii and giants and Aladdin lamps, of tigers and elephants the country of a hundred nations and a hundred tongues, of a thousand religions and two million gods, cradle of the human race, birthplace of human speech, mother of history, grandmother of legend, great grandmother of tradition

On the other hand there were westerners who were simply dismissive. Thomas Macaulay, who introduced Indias first penal code, wrote that the entire body of Indian philosophy was worth less than a single bookshelf of European books. Winston Churchill was ruder still, describing India as a beastly country with a beastly religion and no more a united country than the Equator.

Next page