TO MIKE, BEST FRIEND & TRUE LOVE

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication

Data Farrell, Mary Cronk.

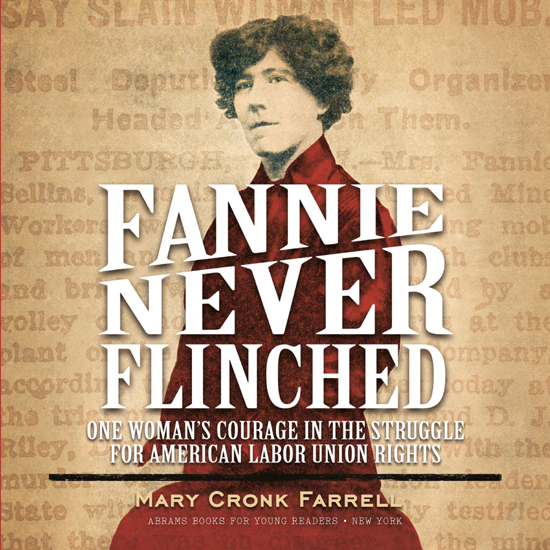

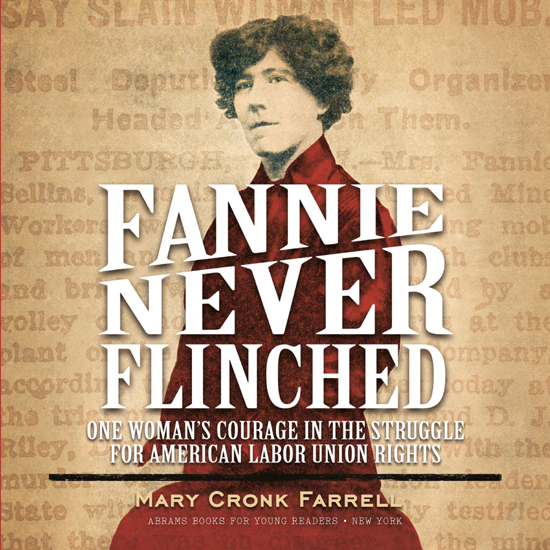

Fannie never flinched : one womans courage in the struggle for American labor union rights / Mary Cronk Farrell.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-4197-1884-7 (hardcover)

eISBN 978-1-6131-2972-2

1. Sellins, Fannie, 18721919Juvenile literature. 2. Women labor leadersUnited StatesBiographyJuvenile literature. 3. Labor unionsOrganizingUnited StatesHistoryJuvenile literature. 4. Labor unionsUnited StatesHistoryJuvenile literature. I. Title.

HD6509.S45 F37 2016

331.88092dc23

2015040020

Text copyright 2016 Mary Cronk Farrell

Cover and book design by Maria T. Middleton

Published in 2016 by Abrams Books for Young Readers, an imprint of ABRAMS. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

Abrams Books for Young Readers are available at special discounts when purchased in quantity for premiums and promotions as well as fund-raising or educational use. Special editions can also be created to specification. For details, contact specialsales@abramsbooks.com or the address below.

115 West 18th Street

New York, NY 10011

www.abramsbooks.com

IMAGE CREDITS

: Kenneth Rogers Collection, Atlanta History Center, Atlanta, GA.

CONTENTS

Young eyewitnesses to the fatal shooting of Fannie Sellins, including Stanley F. Rafalko (third from right). Brackenridge, Pennsylvania, August 1919.

A STORM CENTER FOR BULLETS

NATRONA, PENNSYLVANIA, AUGUST 26, 1919

NATRONA, PENNSYLVANIA, AUGUST 26, 1919

N ear suppertime, gunshots echoed among the small frame houses of Natrona, Pennsylvania. People ran out to see what was happening. Seven-year-old Stanley F. Rafalko was on his way to the corner store to get his father a packet of cigarettes. When he came out, he saw sheriffs deputies beating a man with blackjacks, and shooting over the heads of a crowd of women and children.

Dozens of witnesses say a woman named Fannie Sellins herded a group of children toward safety behind the Rafalko familys backyard gate.

Stop, before someone gets hurt! Fannie shouted at the deputies.

The officers turned their weapons on her.

Stop! she shouted again.

The local newspaper would later report she appeared to be a storm center for deputies bullets.

FANNIE STITCHES TOGETHER A DREAM

ST. LOUIS, MISSOURI, 1897

ST. LOUIS, MISSOURI, 1897

F annies head pounded from the racket of the high-speed sewing machines. Dozens of mechanized needles pumping up and down sounded a continuous clickety-clack, clickety-clack over the rumble of foot treadles and the whir of spinning spools of thread.

Faster! the boss shouted. Work faster!

Fannie longed to stretch her arms and legs and straighten her back, but she kept a firm hand on the fabric, feeding it steadily under the needle. One stray glance and the needle could tear through her finger. It happened once or twice a day to some girl in the factory.

You bleed on the fabric, you pay for it, the boss always said.

Fannie worked at one of two sweatshops owned and operated by the Marx & Haas Clothing Co., the largest clothing manufacturer in St. Louis. She sewed silk-lined hunting coats, each with eleven pockets. Finishing a pocket, Fannie rubbed her bleary eyes and moved on to the next.

Fannie Mooney Sellins was born in 1867, the oldest daughter of an Irish family living in Cincinnati, Ohio. Her father worked as a house-painter, and her mother worked at home caring for the family. Fannie had one older brother, a younger sister, and three younger brothers. In the 1870s, the Mooneys moved to St. Louis, Missouri, where Fannie went to school, learned to read and write, and finished the eighth grade.

She eventually married Charles Sellins and they had four children. Charles died when the youngest was still a baby. To support her family, Fannie went to work at the garment factory. Coughing from the sweatshops foul air, Fannie dropped the presser foot onto a new seam. Most young seamstresses working with her at the garment factory in St. Louis never had the chance to go to school. Girls as young as ten and women old enough to be grandmothers labored alongside her. They worked ten- to fourteen-hour days, six days a week. The building was hot and stifling in the summerand bitter cold in the winter.

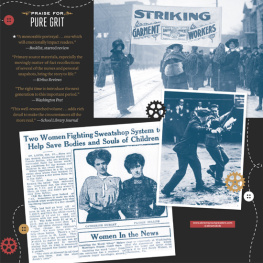

Women and girls at a factory similar to the one where Fannie worked pause their sewing machines for a photograph. Notice the male supervisor standing behind the workers. New York, c. 1910.

Rose Schneiderman, like Fannie, a garment worker and union organizer, works next to the large pile of fabric that makes up her days assignment. New York City, 1908.

All the doors were locked from the outside at 7:15 each morning. Sometimes it made me sick to think what would happen in that big flimsy barracks if a fire should come, Fannie said.

The families of most of the seamstresses had immigrated from country villages in Italy, Poland, and Russia, just as the Irish had come fifty years before, hoping for a better life in America.

Though poor and unable to read or write, they knew how to work hard, which was exactly what garment manufacturers in St. Louis wanted. Like Fannie, the new immigrants barely earned enough to live on, averaging less than five dollars a week ($145 today). If anyone complained, the boss could fire them. There were always immigrants desperate for jobs.

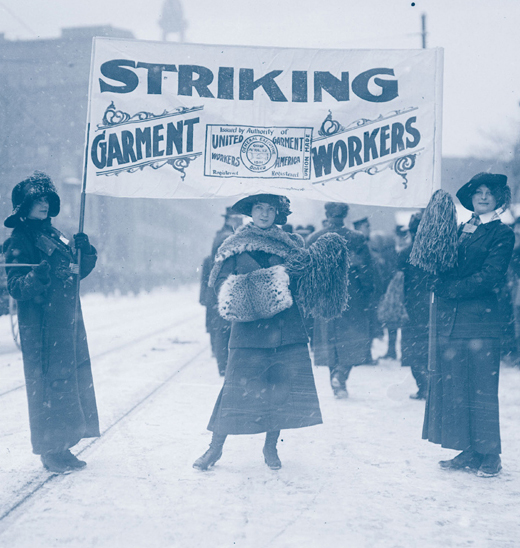

Fannie heard seamstresses in Chicago and New York City had banded together and demanded higher pay and safer working conditions. They had joined a union, the United Garment Workers of America, or the UGWA.

Toiling at her sewing machine, Fannie stitched together a dream. If women and girls in other cities could organize a union to improve their jobs, those in St. Louis could, too! During brief lunch breaks, she spoke with her co-workers. If we earned a fair wage, your children wouldnt have to work, she said. They could go to school.

Next page

NATRONA, PENNSYLVANIA, AUGUST 26, 1919

NATRONA, PENNSYLVANIA, AUGUST 26, 1919