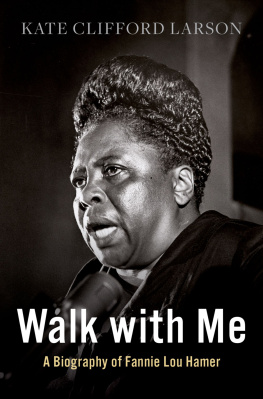

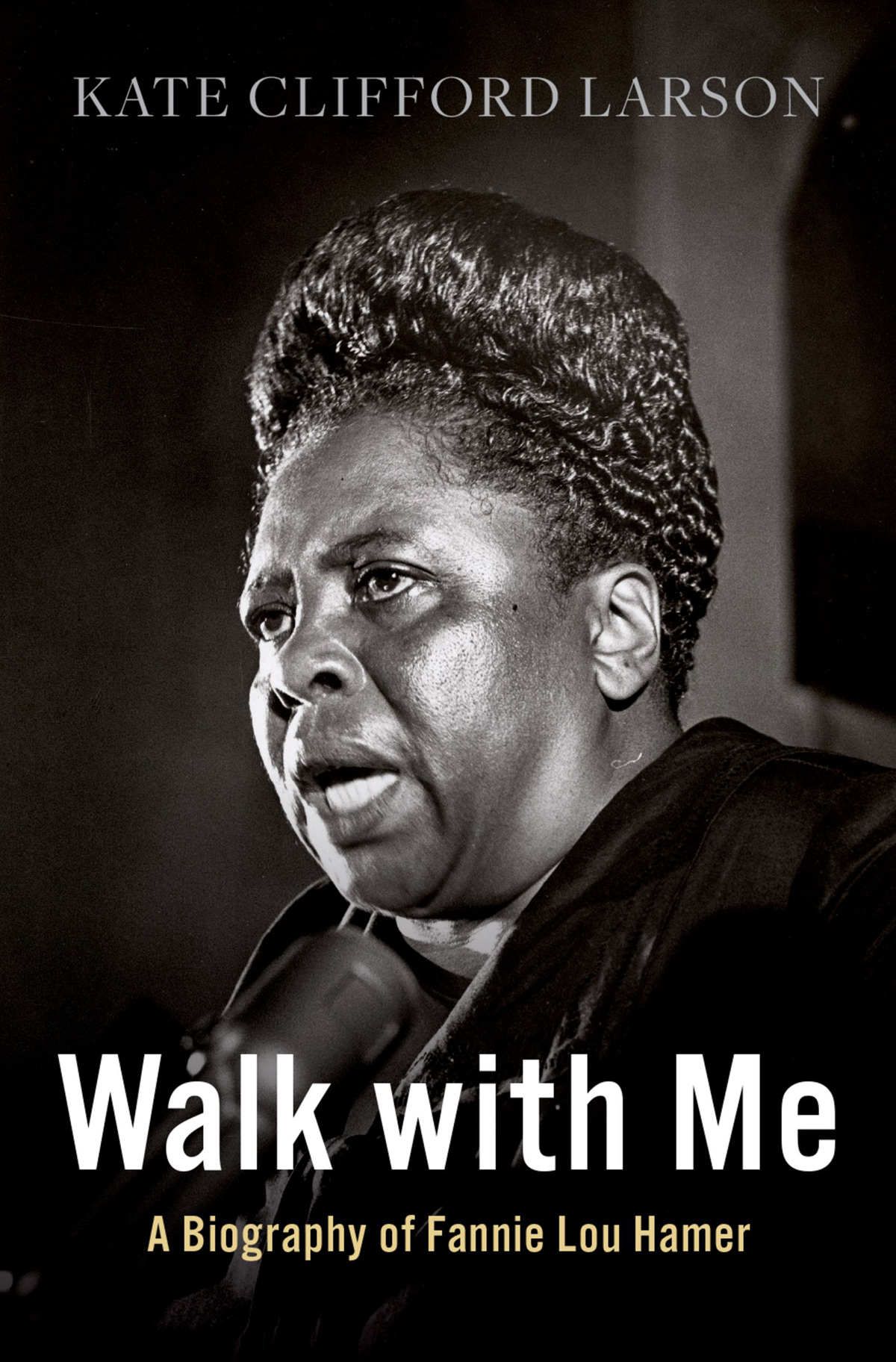

WALK WITH ME

Fannie Lou Hamer with husband Pap and friends. Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos 1970.

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Kate Clifford Larson 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 9780190096847

eISBN 9780190096861

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190096847.001.0001

For Jack and Jamesmay they grow up and live in a world with heroes like Fannie Lou Hamer

Contents

Chapter 1

Another Kind of Slavery

Chapter 2

Delta Blues

Chapter 3

Mississippi Appendectomy

Chapter 4

Crossroads

Chapter 5

The New Kingdom

Chapter 6

Winona

Chapter 7

Reborn

Chapter 8

One Man, One Vote

Chapter 9

Mississippi Goddam

Chapter 10

Atlantic City

Chapter 11

Keep Your Eyes on the Prize

Chapter 12

This Little Light of Mine

SHE WORE A BORROWED dress, one suitable for such an important occasion. A Mississippi sharecropper, she never had new things. Used, reused, patched, and patched againthese defined the fabric of her everyday existence. Someone loaned her white shoes and a white purse, too. From her seat at the table at the front of a packed hearing room, she scanned the faces of the men and women waiting to hear her testimony. The din of conversations and rustling papers and creaking chairs muffled the noise of whirring television cameras. She folded her hands to steady herself. A man to her right gave her the cue to start.

Mr. Chairman, and to the Credentials Committee, my name is Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer, and I live at 626 East Lafayette Street, Ruleville, Mississippi, Sunflower County, the home of Senator James O. Eastland and Senator Stennis. It was the thirty-first of August in 1962 that eighteen of us traveled twenty-six miles to the county courthouse in Indianola to try to register to become first-class citizens. Her white landlord, she said, evicted her when she returned home that night from Indianola because, he told her, we are not ready for that in Mississippi.

The hearing, held on August 22, 1964, in a hotel ballroom in Atlantic City, New Jersey, tendered testimony from Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights activists challenging the right of Mississippis all-white delegation to participate in the Democratic National Convention. Mississippi denied its Black citizensnearly half its populationthe right to vote, and therefore its delegates did not truly represent the interests of the people. Hamer and more than sixty other Mississippians had gone to Atlantic City to press their case to unseat them.

It was late in the afternoon, and the summer humidity seeped into the crowded room. Hamers brown skin glistened with sweat. The committee members shifted and settled in their seats, and the chatter in the room subsided into a few whispers. The white Mississippi delegates shook their heads in disgust while she spoke. Without notes, from memory, from her heart, Hamer recounted the struggles, terror, and violence she had endured trying to do the most basic thing a citizen of any country can do: register to vote.

Her Mississippi drawl ebbed and flowed through her words, giving them a cadence that drew the audience in. She described the death threats and gunshots that had rewarded her demands for civil rights. The room grew quiet. When she recounted how brutally the police had beaten her one day for standing up, eyes welled with tears.

Her eight-minute plea ended with a question that haunted many for years afterward: Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hooks because our lives be threatened daily, because we want to live as decent human beings, in America?

President Lyndon B. Johnson, eager to secure the Democratic Partys nomination for the presidency, tried to stop her from being heard. Caught off guard by Hamers testimony and the prominence it was being given, he called a press conference in the middle of it to draw the news cameras away from Atlantic City and to the White House, where he made an unmemorable three-minute statement. Johnson feared losing the support of southern delegates, a powerful coalition of segregationists who held the Democratic Party hostage to white supremacy. Johnson, however, needed to win so that he could pass long-overdue civil rights legislation that progressive Democrats demanded. By the time the television networks returned to live coverage of the hearing in Atlantic City, Hamer had left the room.

Johnson miscalculated, however. The television cameras had kept rolling throughout her speech, capturing her every word, and the evening news programs replayed her testimony and the ovation that followed. The whole nation watched as a dirt-poor Mississippi sharecropper with a sixth-grade education shamed them into acknowledging how deeply and profoundly broken American democracy had become. That day, Fannie Lou Hamer called on Americans to walk with her toward equality and justice for all.

No one suspected that her speech would be a defining moment in the civil rights movement. There were other such moments, some grisly, some glorious, but Hamers direct appeal gave the movement a voice.

Black Americans struggle for equal rights as citizens during the mid-twentieth century was but another iteration of a battle that had been waged since the countrys founding. White supremacy had repressed the freedoms of millions of African Americans by denying them social, political, and economic parity. Through segregation, voter suppression, economic dominance, and brute-force violence, whites had exerted control over Black communities. The extremes of white supremacy flourished in the Deep South, even as the rest of the nation moved haltingly forward with integration after the Supreme Courts 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education. In Fannie Lou Hamers Mississippi there was no progress at all, and the zealousness with which whites sought to maintain control of every aspect of life for the states Black citizens was breathtaking.

Young people involved with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), an activist organization founded in April 1960 and dedicated to civil and human rights, had come to Mississippi in 1961 to empower local people to register to vote. When those young SNCC workers met her, Hamer was living with her husband and children on a cotton plantation owned by a wealthy white family. Like so many Blacks in the agricultural fields of Mississippis Delta, they survived in abject poverty despite working fifteen hours a day. The SNCC soon recognized her giftsher unforgettable singing, her commanding presence, her determination to overcome debilitating segregation and oppression. She and the young civil rights activists formed a bond. They would become the catalyst she needed to rise up and demand equal opportunity for herself and her neighbors. And they needed Fannie Lou Hamer to remind them of their mission.