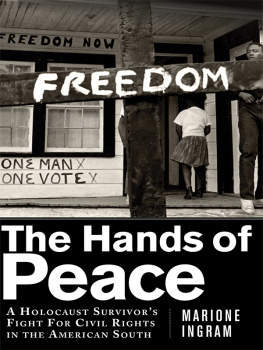

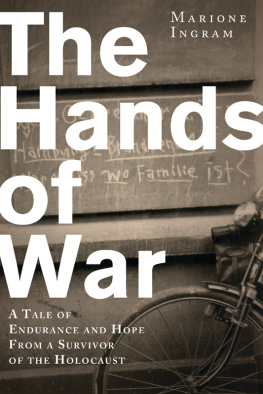

Copyright 2015 by Marione Ingram

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

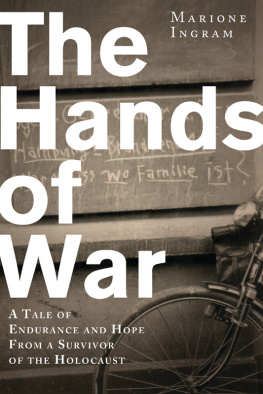

Cover design by Brian Peterson

Cover photo courtesy of Marione Ingram

Print ISBN: 978-1-63220-289-5

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-63220-851-4

Printed in China

For the women of Mississippi who fought and are still fighting for their rights, and to Daniel.

C ONTENTS

F OREWORD

Imagine knowing, from the age of five, that there were people who wanted you dead. Or having to deal with frequent bombings of your hometown, but being denied entrance to a bomb shelter because you were different. Or, while still a child, finding the strength, and the hope, to save your mother from killing herself, after she had lost all strength and given up all hope.

Those of you who have read The Hands of War know that I am talking about Marione Ingram, a remarkable woman who described in that book her experiences growing up Jewish in Hamburg, Germany, and howmiraculouslyher immediate family survived the Holocaust. In this, her second memoir, Marione takes us on a far different journey, one that details her life of activism, which was no doubt inspired by the horrific attitudes and events that robbed her of any sense of childhood, experiences that taught her what it was like to be the target of discrimination.

I first met Marione over fifty years ago outside a Chinese take-out place in Washington, DC, where I was working as an attorney with the United States Department of Justice. She and her husband, Daniel, happened to know the person I was waiting to dine with, and we made quick introductions and struck up an easy conversation. Daniel and Marione were quite interested in the work I was doing at the time, which involved voting rights in the very much still-segregated South, and I was curious to learn more about their backgrounds and what led to their deep interest in social justice.

Soon, I found myself invited to their home, which was a magnet for civil rights activists like James Baldwin, Harry Belafonte, Marion Barry, and others, not only for the discourse that occurred there, but also because it was a joyful place. Marione would later tell me that this was one of the major differences between the Holocaust and the civil rights movement: Jews during the Holocaust had no cause for celebration, but those fighting for civil rights often found joy in their work while, at the same time, participating in acts of defiance that were at times quite dangerous and always courageous. In The Hands of Peace , Marione shares many of the rich stories from that time period, and we also learn about how she and Daniel became so frustrated with the Reagan administration that they sold their home in the United States and moved abroad in protest.

A child who never gave up hope, Marione became an activist who shared her inherent optimism with everyone with whom she came into contact. Her inspiration and determination were infectious, and the stories she shares in the pages that follow will, I hope, continue to spread her message: a message about not giving up on what is right, about fighting for what you believe in, and about living a life full of intention and without regret.

Thank you, Marione, for sharing yourself with the world.

Thelton Henderson

P REFACE

Unlike the Holocaust, which claimed the lives of millions of Europeans in the 1940s, the American civil rights movement twenty years later changed the lives of millions for the better. It was my misfortune to be among the European victims of racism, and my great good fortune to later play a small but impassioned role in a nonviolent movement to empower American victims of racism. I was grateful for the opportunity to join hands with others in a movement for social justice that eventually transformed me more completely than it transformed America. I stopped being a surviving victim of genocide and war and became an activist opponent of both.

Growing up, I couldnt possibly know that I was simultaneously experiencing Germanys attempt to exterminate all European Jews and the deadliest man-made firestorm in history. But the people responsible for both knew, and they knew it was wrong. Everyone knows that no cause has the right to kill children for any reason whatsoever, and that collective enforcement of such a law would severely limit most of the evil that men do. Yet racism, fanaticism, and greed trump child protection even in the primary-school classrooms of a military superpower.

In the civil rights movement, there were hundreds of known and unknown heroes, people who were beaten nearly to death and didnt quit, who were imprisoned and jailed dozens of times, not knowing whether they would get out alive; people whose homes and churches were bombed , who lost jobs and loved ones; people who were shadowed by known assassins, lived every day for years under threat, who could not rely on the police or courts for anything but abuse and were expected to remain pacific, patient, and sane in the face of societys schizophrenic apprehension of equality.

I was not one of those heroes. At times I shared space in the same leaky boat, but with skin tones that would have given me privileged access to a limited number of life preservers. I had, however, come directly from a hell that was even more deranged, cruel, and lethal, and much better organized for genocide. It is because of that perspective and the insight it provides into racisms ability to create ever more terrible conditions that I invite readers to continue.

Marione Ingram

Chapter One

Love and War

I didnt want to go back, and I couldnt tell Daniel why. I couldnt tell myself why. Perhaps the story of Orpheus and Eurydice had made too much of an impression on me as a child. Orpheus looked back at Eurydice while leading her out of Hades, and she was forced to return to the land of the dead forever because Satan had told Orpheus: Dont look back! But I knew that Eurydices tragic fate wasnt the reason I was unresponsive whenever Daniel, my husband and lover for more than fifty years, wondered aloud what life was like today in Mississippi. When I had gone there in 1964, Id felt like I was entering Americas Heart of Darkness. Having escaped alive, I was still afraid almost fifty years later of what I would see if I went back.

Perhaps I felt about Mississippi the way I felt about Germany years after its defeat and my flight to America. Without pressuring me, Daniel had somehow persuaded me to go back to Germany when, for me, it was still Nazi Germany even though forty years had passed since the official end of World War II. We went to Hamburg in 1985 on an overnight ferry from England, intending to stay only long enough to purchase a car. The plan was for us to drive from there to Tuscany where we would live while Daniel wrote the great American civil rights novel. I would make art while he was doing this, surrounded by timeless beauty and immersed in a culture as stimulating and warm as the regions red wine and brilliant sunshine.