Contents

Guide

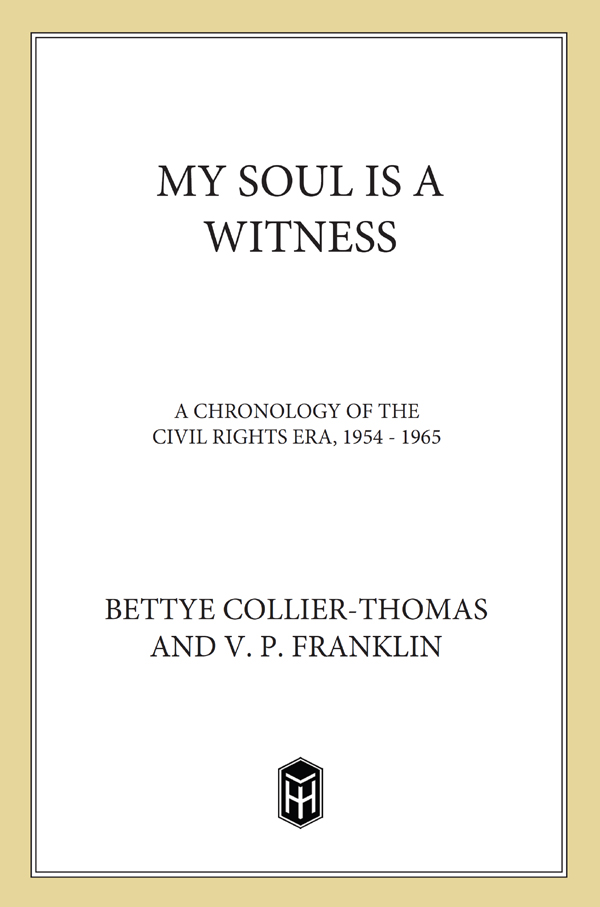

MY SOUL IS

A WITNESS

A Chronology of the Civil Rights Era

19541965

Bettye Collier-Thomas and V. P. Franklin

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY NEW YORK

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: http://us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

IN MEMORY OF

THE VERY REVEREND WAYLAND EDWARD MELTON

(19491997)

My Soul Is a Witness has been many years in the making. It began in 1994 with our concern that, though there was a great deal of material on the Civil Rights Movement, there was no overview that captured the extent and interconnections of activities at the local, state, and national levels. Moreover, there was very little information on the movement in the North, Midwest, and West.

Our research and efforts to coordinate the voluminous data on the Civil Rights Movement were greatly aided by the students and staff at the Temple University Center for African American History and Culture. Michael Collins, Mitsuru Sono Walker, and Benjamin Hassing, undergraduate students in the History Department, followed up leads in Jet magazine, The New York Times, and the Southern School News, which were integrated into the chapters. Danielle Smallcomb, a research associate at the Center, performed an inestimable service in painstakingly codifying data found in Jet magazine during the period after 1960. Jerry Bjelopra, a doctoral student in the History Department, was most helpful in identifying sources for the bibliography. Richard Woodland, a research associate at the Center, used his excellent computer skills to separate the data by subject, and Joanne Hawes Speakes, Marie McCain, and Lorraine Harris at different times performed typing and organizational tasks. We thank Jack Franklin, Terri Rouse, and Aileen Rosenberg at the African American Museum of Philadelphia for granting permission to use several photographs. We owe a debt of gratitude to all of these people for the individual and collective contributions they made to this work. We also thank our agents, Charlotte Sheedy and Neeti Madan, and the editors at Henry Holt, Tracy Sherrod, Elise Proulx, and Elizabeth Stein.

On a personal level, the love and support of our families and friends have nurtured and sustained us: Charles Thomas, Katherine Collier, Joseph Collier, Thelma Polk Collier, Ida Mae Thomas, Christine Lee, Vincent F. Franklin, Ed Collins, Sandra B. Motz, John Hope Franklin, Mary Frances Berry, Sharon Harley, Cheryl Townsend Gilkes, Lillian S. Williams, Genna Rae McNeil, Gloria Harper Dickinson, James Turner, Simeon Booker, Rosalyn Terborg Penn, Kenneth Kusmer, Craig Eisendrath, Anise Ward, Julie Mostov, Eric D. Brose, the Rev. Elizabeth Colton, the Rev. William Shepard, and the Rev. Paula Lawrence Wehmiller.

At the end of every Sunday religious service at Philadelphias Cathedral Church of the Savior, the Very Reverend Wayland E. Melton fervently sang out and asked, Wholl be a witness for my Lord? because he understood the songs power in evoking the spirit of struggle of past, present, and future generations.

My soul is a witness

for my Lord,

My soul is a witness

for my Lord

O, wholl be a witness

for my Lord?

O, wholl be a witness

for my Lord?

My soul is a witness

for my Lord,

My soul is a witness

for my Lord.

TRADITIONAL NEGRO SPIRITUAL

This is the first book to provide a comprehensive survey of the issues, events, and personalities that defined the civil rights era and to place them in proper sequence, locale, and perspective. It extends the examination of civil rights activities between 1954 and 1965 beyond the southern states to the rest of the country. Although Martin Luther King, Jr., was a towering figure in the civil rights era, this volume includes the thousands of people, places, and events that the Civil Rights Movement encompassed. While King was the center of so much that took place during that time, the Civil Rights Movement was much more than any one personality, and it engulfed all parts of the nation and touched most of the important sociocultural issues.

When we began this research we had no idea how extensive and rich the data were. We discovered that civil rights activity was not exclusive to any city, state, or region, but reached all levels of American society.

In order to include as much as possible in this study, we have supplemented the basic chronology with five features per chapter, allowing us to explore some larger topics in more depth. Features also permit us to highlight issues well known at the time but since forgotten.

Historical Overview

In the period from 1954 through 1965 Americans witnessed profound changes in the nature of race relations. At the beginning of 1954 black-white relationsnot just in the South, but throughout the nationwere defined by legalized and de facto systems of segregation that most closely resembled the practice of apartheid or separate development that existed in the Republic of South Africa from the late 1940s until the 1990s. In southern law, and in northern and western practice, under American apartheid black and white citizens were forbidden to commingle publicly, and citizens of African descent were barred from restaurants, hotels, theaters, schools, railroad cars, and other public accommodations reserved for whites only. The system of legal or Jim Crow segregation was implemented to keep blacks and whites separated from cradle to grave.

As a result of the litigation carried out by Thurgood Marshall and the other lawyers for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Supreme Court decision that upheld the separate but equal doctrine in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) was declared unconstitutional not merely because the separate public facilities provided for citizens of African descent were rarely equal, but because legal segregation of the races was found to be in violation of the equal protection of the law clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. While the Brown v. Board of Education decision was directed at public education specifically, NAACP lawyers and others used the ruling to attack legal segregation in other areas of public life. Finally, with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the U.S. Congress banned discrimination on the basis of race, creed, color, or nationality by any institution or facility open to the public.

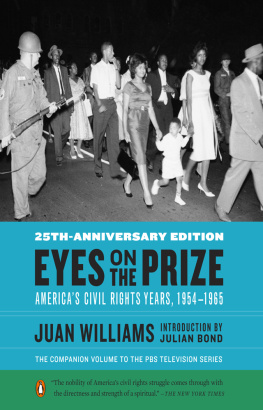

With the launching of the Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott in December 1955, the Civil Rights Movement entered a new phase of nonviolent direct action protest. While boycotts, picketing, sit-ins, and various other forms of nonviolent actions had been employed before 1955 to protest de jure and de facto segregation in various parts of the United States, the Montgomery bus boycott ushered in a new wave of activism that spread throughout the South and to other parts of the country. While historians continue to disagree about when the Civil Rights Movement began, or when the