D rafted in 1787, the U.S. Constitution is the oldest written national constitution still in use. Many of the Constitutions supporters (James Madison, the Constitutions principal author, among them) had initially argued that a Bill of Rights was unnecessary. In Federalist 84, Alexander Hamilton wrote that bills of rights are, in their origin, stipulations between kings and their subjects, reservations of rights not surrendered to the prince. No need, Hamilton asserted, for such a document in a constitution founded upon the power of the people, and executed by their immediate representatives and servants; here, the people surrender nothing; and as they retain everything, they have no need of particular reservations.

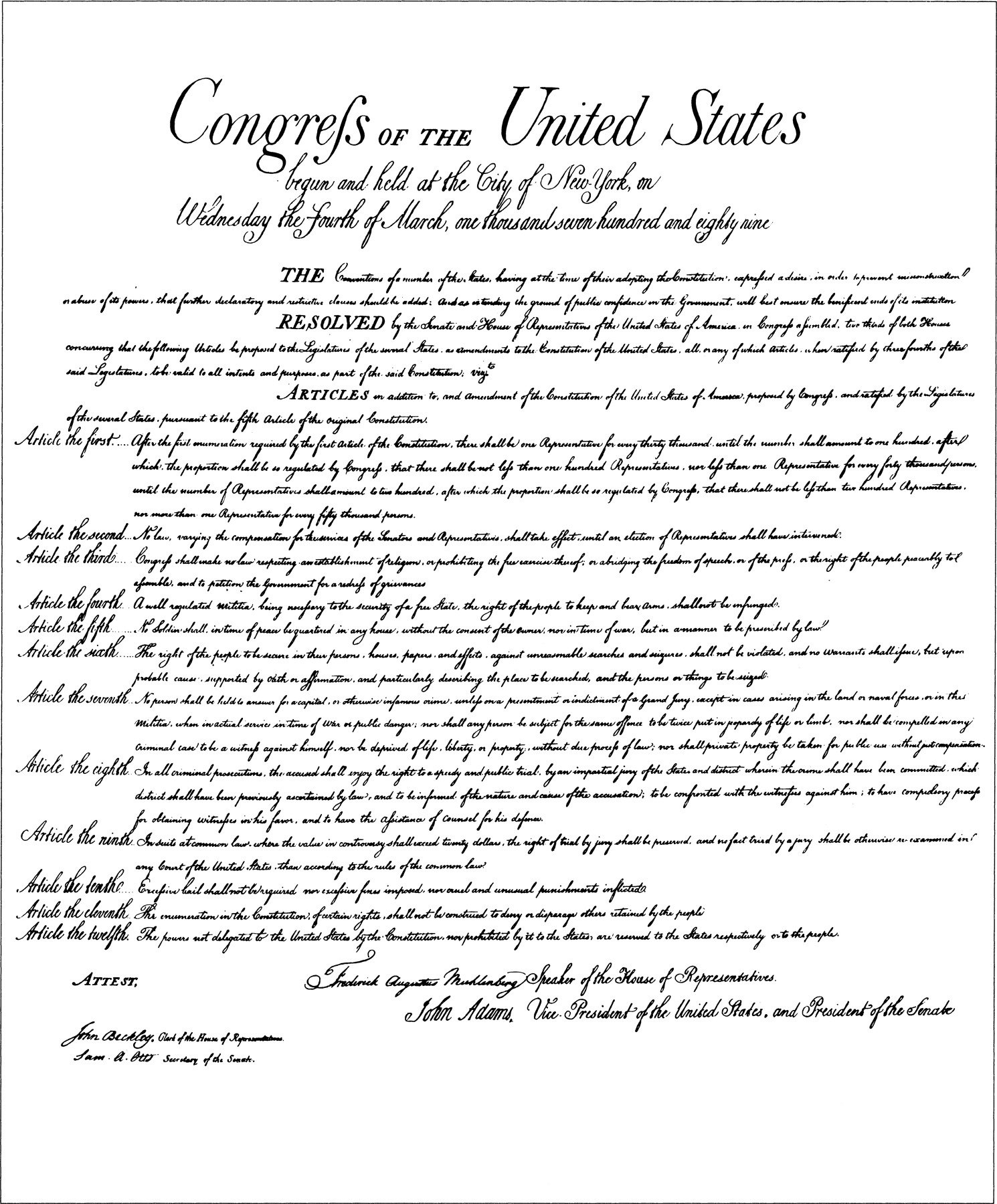

But Madison, Hamilton, and the other Federalists could not win over the opposition on this point. As one of the great compromises that helped assure passage of our founding document, the first Congress passed a terse Bill of Rights, adopting provisions submitted by Madison himself. Ratified by the states in 1791, the Bill of Rights contains ten amendments. Since then, the Constitution has been amended only seventeen times.

Neither the original Constitution, nor the Bill of Rights, bestows any rights on individuals. To the Framers, no document could perform that task. In their view, individual rights antedated the state and thus were not the states to confer. As Jefferson wrote in our principal rights-declaring document, the Declaration of Independence: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness. Thus, the Bill of Rights assumes the existence of fundamental human rightsfor example, freedom of speech, press, and assemblyand simply instructs the state not to interfere with those rights.

Madison recognized that if the Bill of Rights was not to be a mere parchment barrier to the will of the majority, the judiciary would have to play a central role. If [a Bill of Rights is] incorporated into the Constitution, independent tribunals of justice will consider themselves in a peculiar manner the guardians of those rights; they will be an impenetrable bulwark naturally led to resist every encroachment upon rights.

While that sentiment has brightened the spirit of the men and women privileged to serve on the federal bench, the judiciary does not stand alone in guarding against governmental interference with fundamental rights. Responsibility for securing those rights is a charge we share with the Congress, the president, the states, and with the people themselves. As one of our greatest jurists, Judge Learned Hand, put it, the spirit of liberty that infuses our Constitutiona spirit that is not too sure it is right, one that seeks to understand the minds of other men and women and to weigh the interests of others alongside its own without biasmust lie, first and foremost, in the hearts and minds of the men and women who compose this great nation.

It manifests no disrespect for the Constitution to note that the Framers were gentlemen of their time, and therefore had a distinctly limited vision of those who counted among We the People. Not until adoption of the postCivil War Fourteenth Amendment did the word equal, in relation to the stature of individuals, even make an appearance in the Constitution. But the equal dignity of all persons is nonetheless a vital part of our constitutional legacy, even if the culture of the Framers held them back from fully perceiving that universal ideal. We can best celebrate that legacy by continuing to strive to form a more perfect Union for ourselves and the generations to come.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Associate Justice

Supreme Court of the United States

A merica is a nation based on an idea. That idea, as expressed in the Declaration of Independence, is that all people are endowed with certain unalienable Rights and that the purpose of government is to secure these rights. Rights are at the center of Americans national identity. Rights are why many people make America their home.

In 1791, Americans added a list of their rights to the Constitution. These first ten amendments became known as the Bill of Rights. But putting rights on paper is not enough. As the late Learned Hand, one of Americas greatest judges, said: Liberty lies in the hearts of men and women; when it dies there, no constitution, no law, no court can save it. In Hands opinion, the real protectors of liberty were not constitutions or courts, but citizens.

Justice William O. Douglas of the U.S. Supreme Court, in his book A Living Bill of Rights, agreed with Judge Hand:

What our Constitution says, what our legislatures do, and what our courts write are vitally important. But the reality of freedom in our daily lives is shown by the attitudes and policies of people toward each other in the very block or township where we live. There we will find the real measure of A Living Bill of Rights.

The purpose of this users guide to the Bill of Rights is to help citizens make the Bill of Rights a living document in their everyday lives. Unfortunately, the Bill of Rights did not come with an instruction manual. The language of 1791 can often be difficult to understand and apply more than 200 years later. Therefore, this guide describes the history of each right in the Bill of Rights and explains how the Supreme Court interpreted those rights. It also tells the stories of many ordinary people who have helped keep the Bill of Rights a living documentnot just an artifact stored under glass at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. Making the Bill of Rights come alive in our communities is the best way to secure those rights for generations to come.