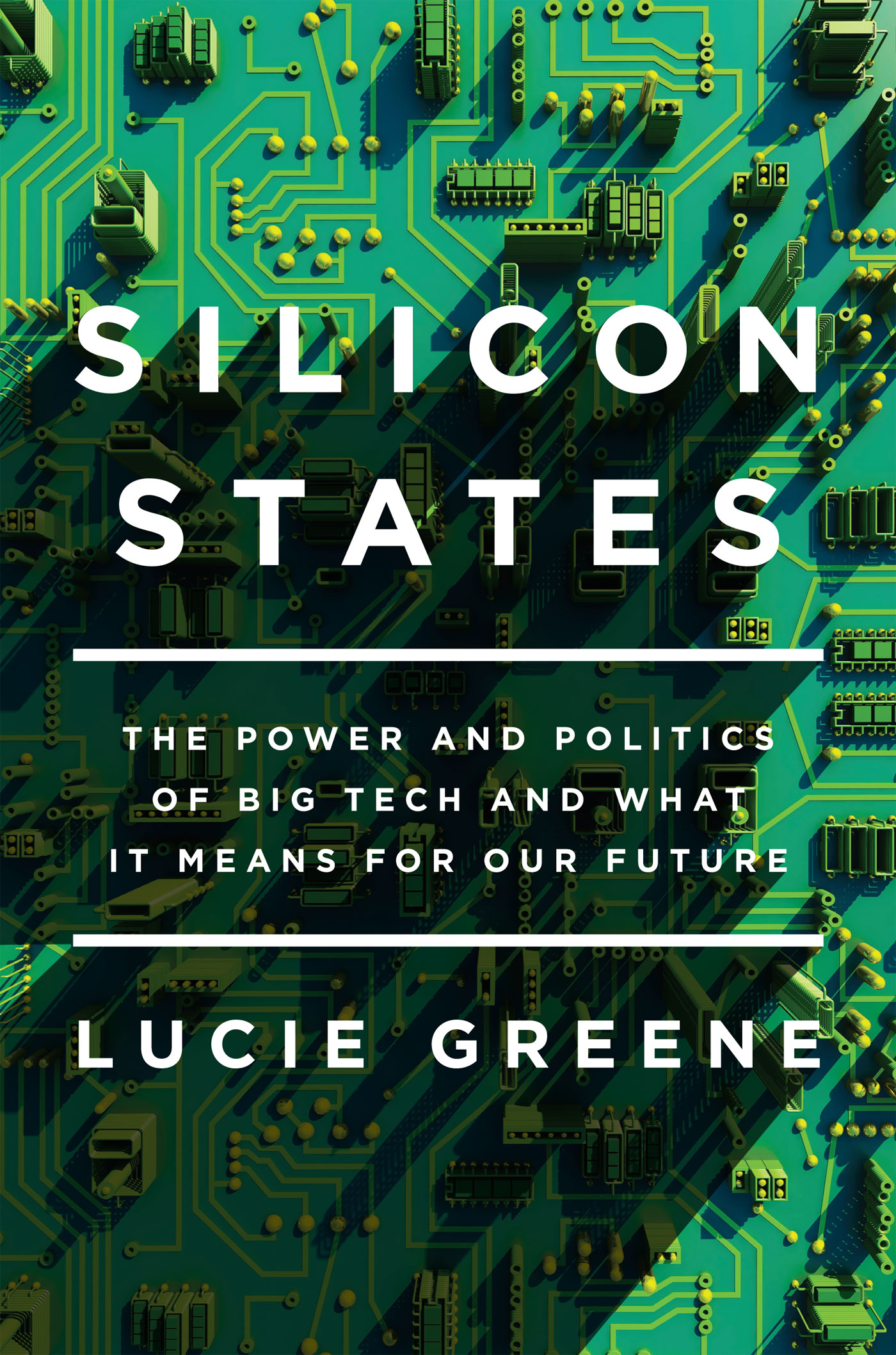

SILICON

STATES

Silicon States

Copyright 2018 by Lucie Greene

First hardcover edition: 2018

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Greene, Lucie, author.

Title: Silicon states : the power and politics of big tech and what it means for our future / Lucie Greene.

Description: Berkeley, California : Counterpoint, 2018.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018010153 | ISBN 9781640090712 | eISBN 9781640090729

Subjects: LCSH: High technology industriesSocial aspectsUnited States. | TechnologyPolitical aspects. | Social responsibility of business.

Classification: LCC HC79.H53 G74 2018 | DDC 338.4/760973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018010153

Jacket designed by Darren Haggar

Book designed by Jordan Koluch

COUNTERPOINT

2560 Ninth Street, Suite 318

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.counterpointpress.com

Printed in the United States of America

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Dedicated to my friends and family, my constant supporters

With special thanks to J. Walter Thompson

CONTENTS

SILICON

STATES

Introduction

A Changing Landscape

T he year is 2014. Crowds have gathered for one of the final talks of the day at the Web Summit, the annual tech hurrah. Every year since 2009, European startups, marketers, social media managers, and hangers-on convene for this affair, flocking to Dublin during perhaps the citys soggiest, purple-skied month. At the conference, attendees walk through the acres of stands collecting flyers, watching motivational talks, and gawking at the great and the good of Silicon Valley who are flown in to spout their entrepreneurial wisdom onstage. At night, everyone swigs pints of Guinness. (Its since migrated to Lisbon, but the format remains the same.)

Each year I attend about twenty of these conferences, with their interchangeable executives in lapel microphones reciting carefully crafted soundbites and bombastic statements about whats to come in technology, retail, marketing, and beyond. Data is the new oil! Content is king! Disrupt yourself to survive! I and a migratory pack of journalists and tech executives attend them in hotspots around the world to gain access to these self-proclaimed visionaries and speak on behalf of our companies about what we believe the future holds. The schedule has become ever more crowded over the past few years, each new gathering competing for a share of corporate travel budgets and Buzzfeed column inches. They have become well-oiled, navel-gazing marketing events, albeit with a lot of shouting. Ive been to so many that they have started to blend into one long, undifferentiated TED talk.

This one, though, was different.

Caroline Daniel, then editor at FT Weekend, was gleefully ribbing billionaire Peter Thiel about Silicon Valleys hubristic Change the World sloganeering (that and his recent statement that Europeans have no work ethic). She was also teasing him about what he had next on the agenda, alluding to his obsession with longevity research. Thiel is famed for his efforts to become immortal, in wilder reports even exploring having transfusions of young peoples blood to stay youthfulan act so quintessentially far-out Silicon Valley that it had been parodied on the HBO TV series of the same name. With one eyebrow arched and a flicker of a smile, she asked: So, do you really think you can live forever?

I stopped scribbling notes and looked up. There had been rumblings of Thiel and other Silicon Valley luminaries interest in immortality, but until this moment it had seemed a slightly crackpot endeavor, an idle pursuit for billionaire playboys, not a tangible business pursuit and potential reality. But Thiels unabashed certainty was disarming. He was serious, and, Id soon discover, there were others working in this vein. All of this was a long way from restaurant recommendations or online marketplaces. Silicon Valleys ambitions, it seemed, had spiraled to new levels in breathtaking if unnerving ways.

People today, Thiel said, have been trained not to be enthusiastic about the future and about the promises of technology. Wed come to see space travel and scientific progress in dystopian lights. Whod want to leave the planet after watching a movie like Gravity, he asked, when space exploration was shown in such a way? (This has since become a refrain for Thiel.) We should be more ambitious about solving world problems, he continued. Where had our ambition gone?

Technologists, he argued, were a counterculture in todays society simply for championing the future. Sitting before a crowd of 22,000 prosperous tech nerds, gawking in admiration, this seemed like a stretch to me. But Thiel doubled down on his vision of Valley techies as twenty-first-century punk rockers. Not only were they underrepresented in government, he argued, the government was actually trying to curtail progress, regulating technologies it doesnt understand. Politics, and the ignorance of politicians, was holding us back.

Then Daniel asked, Do you really have the right as the technologist to determine and say were going to change the world?

These questions of rights are always very tricky, Thiel answered, head tilted to one side in thought. You can always flip it around and say what gives the people in [Washington] DC the right to stop medical inventions that could save many peoples lives? What gives people the right to stop technology in one form or another?

I squirmed. Daniel seemed to squirm, too. Thiel continued: Its not as though were living in a perfect world. Were living in a world in which there are enormous problems, where there are many things that are incredibly screwed up. And so I think it is imperative on us to try to fix these problems as quickly as possible. And sometimes that means not asking for permissionbut really asking for forgiveness later.

As I considered Thiels statement in the frenetic years since, it has come to epitomize a distinct attitude developing in the Valley about its role in the world, one characterized by an increasingly nonchalant regard for effecting seismic, irreversible change with an air of distant sociopathic paternalism, especially for those left behind by this relentless drive for progress.

Amid the high-flying urban millennials using on-demand driverless flying cars, after all, countless workers will lose jobs from automation. Fast-food workers will be replaced by machines. Airlines have already replaced ticket stewards and suitcase labelers with machines. In singular, distinct entities, these are all logical efficiencies. But taken together, they represent enormous, painful change for a huge swath of the population; and that change is casually being rationalized by Silicon Valley billionaires as progress.

But is this the progress we want? And do we even realize how fast it is happening? And how irreversibly? Are we comfortable with Silicon Valley defining the future?

I should be clear that when I refer to Silicon Valley, Im talking specifically about the group of businesses that have come to embody the culture and industry of digital technology. In other words, Facebook, Amazon, Uber, Google, Apple, Snapchat, and Teslathe most ambitious and powerful tech companies the world has seen that are attempting to shape our future. Some of them have even been given their own acronym, GAFA (Google, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon). Not all of them are from Silicon Valley geographically, but collectively, this group of businesses has come to embody similar power, influence, and values. Since the resurgence of Apple, tech companies have not only become mass market, they have become globally monumental, region-transcending brands in sync with a powerful new generation of millennial consumers who have incorporated digital socializing, mobile use, and the internet into every facet of their lives.

Next page