Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2019 by Jayson Greene

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Excerpt of Between the Bars, written by Steven Paul Smith, provided by courtesy of Universal Music Publishing Group, copyright Universal Music-Careers, on behalf of Itself and Spent Bullets Music.

A portion of this work originally published as Children Dont Always Live in The New York Times Opinion column on October 22, 2016.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Greene, Jayson, author.

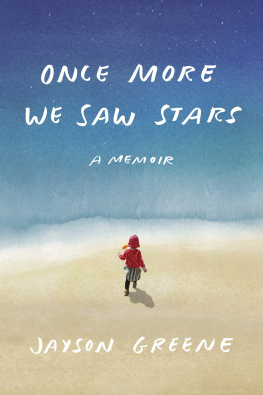

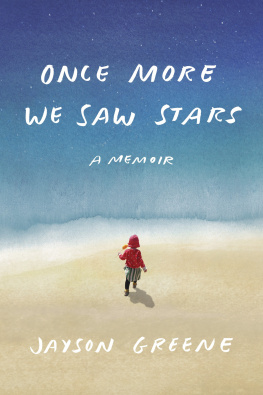

Title: Once more we saw stars / Jayson Greene.

Description: First edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2019. | This is a Borzoi book.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018013866 (print) | LCCN 2018042539 (ebook) | ISBN 9781524733537 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781524733544 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Greene, JaysonFamily. | ChildrenDeathPsychological aspects. | BereavementPsychological aspects.

Classification: LCC BF 575. G 7 G 6897 2019 (print) | LCC BF 575. G 7 (ebook) | DDC

155.9/37083dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018013866

Ebook ISBN9781524733544

Some names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals.

Cover photograph taken by the author, Coney Island, 2015

Cover watercolor by iStock/Getty Images

Cover design by Jenny Carrow

v5.4

ep

To Greta and Harrison

To get back up to the shining world from there

My guide and I went into that hidden tunnel;

And following its path, we took no care

To rest, but climbed: he first, then Iso far,

Through a round aperture I saw appear

Some of the beautiful things that Heaven bears,

Where we came forth, and once more saw the stars.

Dante Alighieri, Inferno

CONTENTS

HOW SHOULD WE START, SWEETIE? Maybe with one of the silly games we invented together. They meant nothing to anyone else, but everything to us. There was the time we pretended, for half an hour, that the ramp outside of a building was an elevator. You would press your finger to a brick; I would make a beeping noise. I would say Going down! and you would run down the ramp, laughing. That was the whole game. It was enough.

Or: Were on the beach. You are two years old. You saw the beach once before, when you were fourteen months; you did not enjoy it. The sun on your skin felt invasive (you shared your mothers aversion to direct sunlight). The sand moving beneath your feet and hands fascinated you at first but quickly unnerved you; the ground had never stuck to you before, nor had it proven unreliable. The sea thundered. You wound up in my arms, squirming.

Today, you are older, and you are unafraid. You are wearing a polka-dot red cardigan over a striped green dress and a bright red hat, and in your left hand is a mango on a stick from the boardwalk vendor. I carry you out past the Coney Island pier; I take off my shoes and set you down with your small shoes on. You run out, mango stick held out carefully to your side. I walk after you.

The ocean is enormous to you, and I sense the thrill of awe and fear little people feel when confronted with the worlds vastness. You look up at me and I smile; I dont seem scared. My shoes are off, I point out; would you like to take off yours? Your eyes go thoughtful, and then you nod. We walk up together to the mouth of the impossible ocean. The wet sand is cold; its only May. Individual sand grains twinkle. Look, sweetie pie, a shell, I say, pointing to your feet. You reach down and scoop it up out of the wet sand. It is a fragment, something that fits between your tiny finger and thumb. There is a clump of sand at its point; you hold it up in my face, grinning, as I pretend to be disgusted.

Ewww!!

You laugh that throaty, snuffly, catching giggle of yours. The waves run closer, reaching us. For the only time in your life, you feel ocean water running over your toes.

The brick fell from an eighth-story windowsill on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. Greta was sitting on a bench out front with her grandmother. The two of them were chatting about a play they had seen together the night before. It was a live-action version of the kids show Chuggington, in which some talking train cars help their friend Koko get back on track after she derails.

Koko got stuck! Greta exclaimed over and over. The moment seemed lodged in her brain, my mother-in-law told us later. She was struck by the simplicity of the predicament, the profundity of the call for help.

Reporters interviewed the aide of the elderly woman who lived on the floorthe woman whose windowsill crumbled. Even in print, I recognized the sickened wonder in her voice, her newly dawning understanding of the malevolence and chaos of the world: It was like an evil force reached down

We left our E-ZPass in the apartment. Stacy and I realize this only upon arriving at the mouth of the tunnel en route to the Weill Cornell ER. The gate fails to lift as we approach and we almost plow through it. The man at the tollbooth tries to reckon with us, incoherent and hysterical and blocking traffic.

Our daughters been in a serious accident, Stacy yells to him.

He peers behind us at the empty car seat, confused. Where is she? he demands.

Shes with my mother! Stacy says. Cars honk as the pressure of the line builds behind us.

Please, she is in the hospital, I interject. Please just let us go.

He waves us on. Just dont get in an accident! he calls into our window as the bar lifts.

Wed received the phone call from Stacys mother, Susan, only twenty minutes before. Oh, Jayson, its so horrible, she had saidher first words. The scenario she described was still sketchy: there had been two chunks of brick; there were paramedics on the scene. Susan was in the back of a second ambulance, and Greta was in the first, already en route to the hospital. Susan had been struck as well, in the legs.

Where is Greta? I demanded.

Shes up ahead, Susan said. Shes breathing on her own now. They told me shes breathing on her own.

Her voice was fuzzy, disoriented, and we heard other muffled voices, paramedics demanding things of her. A male voice cut in behind her, asked Susan something sharply. I could tell from her faltering response that she was struggling to connect the dots.

Susan, please tell me, I said, firmly and slowly. Where did the brick hit Greta? Did it hit her in the head? When I said the word head, I felt something break up my voice, an elemental