FOUNDING EDITOR

Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr.

BOARD MEMBERS

Alan Brinkley, John Demos, Glenda Gilmore, Jill Lepore David Levering Lewis, Patricia Nelson Limerick, James McPherson Louis Menand, James H. Merrell, Garry Wills, Gordon Wood

James T. Campbell

Middle Passages: African American Journeys to Africa, 17872005

Franois Furstenberg

In the Name of the Father: Washingtons Legacy, Slavery, and the Making of a Nation

Karl Jacoby

Shadows at Dawn: A Borderlands Massacre and the Violence of History

Julie Greene

The Canal Builders: Making Americas Empire at the Panama Canal

G. Calvin Mackenzie and Robert Weisbrot

The Liberal Hour: Washington and the Politics of Change in the 1960s

Michael Willrich

Pox: An American History

James R. Barrett

The Irish Way: Becoming American in the Multiethnic City

Stephen Kantrowitz

More Than Freedom: Fighting for Black Citizenship in a White Republic, 18291889

Frederick E. Hoxie

This Indian Country: American Indian Activists and the Place They Made

Ernest Freeberg

The Age of Edison: Electric Light and the Invention of Modern America

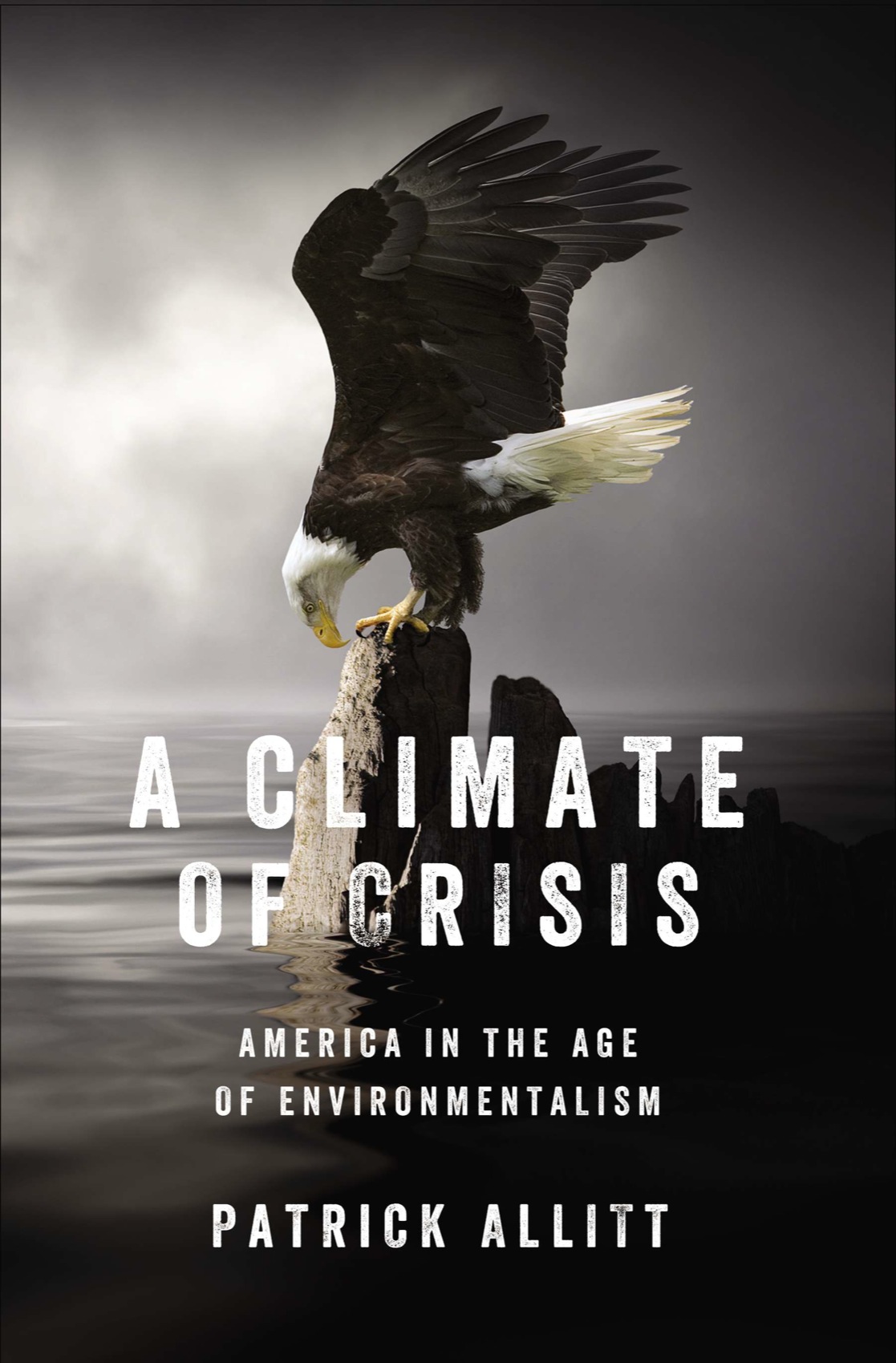

Patrick Allitt

A Climate of Crisis: America in the Age of Environmentalism

ALSO BY PATRICK ALLITT

The Conservatives:

Ideas and Personalities Throughout American History

Religion in America Since 1945:

A History

Im the Teacher, Youre the Student:

A Semester in the University Classroom

Major Problems in American Religious History (editor)

Catholic Converts:

British and American Intellectuals Turn to Rome

Catholic Intellectuals and Conservative Politics in America:

19501985

THE PENGUIN PRESS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA Canada UK Ireland Australia New Zealand India South Africa China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

First published by The Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 2014

Copyright 2014 by Patrick Allitt

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Photograph credits appear .

ISBN 9780698151598

Version_1

FOR

Ernie Freeberg

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Since the early 1990s I have taught undergraduate courses on American environmental history at Emory University. The most dynamic part of this history comes with the decades after World War II. A succession of alarmsabout overpopulation, about pollution, about resource depletion, and about climate changemade the environment newsworthy, and these were the years in which an environmental movement developed in the United States. They were also the years in which Congress mandated environmental reforms.

There are many fine books on aspects of this history, by participants and by historians, but until now there has been no general intellectual history of American environmentalism. When the Penguin Press invited me to write such a book I was glad to accept the offer. My editors, Mally Anderson and Scott Moyers, for whose help I am grateful, wanted me not just to describe and explain the environmental debates of this era but to stake out a clear position.

Let me summarize the books argument. Industrialization caused most of Americas environmental problems, but they were the side effects of a phenomenal achievement. Industrialization brought widespread prosperity to millions, along with improved health, greater mobility, and greater life expectancy. Americans became concerned about environmental problems in the 1960s not because their situation was getting worse but because it was getting better. Now that they had a generally high standard of living they were no longer content to live with poor air quality, polluted rivers and lakes, and the indiscriminate use of powerful chemicals around their children, food, pets, and vacation haunts.

In a bipartisan burst of political activity, late in the 1960s and early in the 1970s, their political representatives across the spectrum legislated for improvements in air and water quality, nurture of endangered species, cleanup of contaminated toxic sites, protection for wilderness areas, and the removal of lead from gasoline. The policy objectives embodied in these acts have been largely achieved, with the result that Americans now breathe much cleaner air than their parents and grandparents, can expect longer and healthier lives, have access to more national parks and an improved chance of seeing charismatic animals that have been brought back from the brink of extinction.

No problem was so menacing during these decades as the possibility of nuclear war. The mood of crisis created by the first atom bombs and the Cold War arms race spread to influence popular ideas on many other issues, including population, resources, and climate change. Two contradictory points of view developed among American thinkers interested in these issues. The pessimistic view, often expressed in crisis rhetoric, was that we were running out of basic necessities and faced a future of constraints, restrictions, and even famines. Its corollary was that a new approach to life was essential, one that was more Spartan and more conservation-minded. The optimistic view, by contrast, was that human ingenuity could deal with the problems thrown up by economic growth and technical innovation. As a result, said the optimists, we can anticipate continued environmental improvement along with benign economic growth, here and through much of the developing world. The future would present us with genuine problems, but we were becoming ever more capable of solving these problems.

Each view had, and continues to have, energetic advocates. The arguments on both sides are powerful, often emotional, and freighted with serious policy implications. My own view is that the optimists have been right on most of these questions. Nevertheless, I hope I have given a fair presentation of each sides views, enabling even readers who disagree with me to learn from the chapters that follow.

In addition to explaining the major policy issues, I have followed several interesting byways, such as the work of ecological scientists and philosophers, environmental historians, deep ecologists and ecofeminists. Their impact on the political debate was not great but their ways of thinking about the issues have an intrinsic interest and sometimes shed a new and unexpected light on the major controversies.

I am grateful for the help and advice of several outstanding colleagues here at Emory, especially Joseph Crespino, Frank Lechner, Jeffrey Lesser, and Tom Rogers. They do not share my views on all of the issues discussed here, but they are friendly and helpful even when, as often happens, they disagree with me. Thanks also to my research assistant Emily Moore, who, as a new college freshman in the fall of 2012, at once took on the arduous task of checking facts and footnotes. Her steadiness and self-discipline match or exceed those of most people twice her age. Any remaining errors are mine, not hers. It is a pleasure to dedicate the book to my friend and former student Ernie Freeberg. Trumping all other debts of gratitude is the one, unpayable even in a lifetime, that I owe to Mrs. Allitt.