Cover

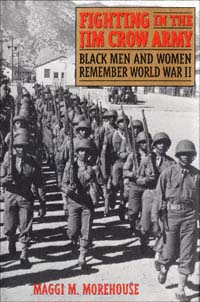

| title | : | Fighting in the Jim Crow Army : Black Men and Women Remember World War II Voices and Visions (Lanham, Md.) |

| author | : | Morehouse, Maggi M. |

| publisher | : | Rowman & Littlefield |

| isbn10 | asin | : | 0847691934 |

| print isbn13 | : | 9780847691937 |

| ebook isbn13 | : | 9780585382166 |

| language | : | English |

| subject | World War, 1939-1945--African Americans. |

| publication date | : | 2000 |

| lcc | : | D810.N4M67 2000eb |

| ddc | : | 940.54/03 |

| subject | : | World War, 1939-1945--African Americans. |

Page i

FIGHTING IN THE JIM CROW ARMY

Page ii

Page iii

FIGHTING IN THE JIM CROW ARMY

Black Men and Women Remember World War II

Maggi M. Morehouse

ROWMAN & LITTLE FIELD PUBLISHERS, INC.

Lanham Boulder New York Oxford

Page iv

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC.

Published in the United States of America

by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

4720 Boston Way, Lanham, Maryland 20706

http://www.rowmanlittlefield.com

12 Hid's Copse Road

Cumnor Hill, Oxford OX2 9JJ, England

Copyright 2000 by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Maps copyright 2000 by Jackie Aher.

All rights reserved . No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Morehouse, Maggi M., 1953

Fighting in the Jim Crow Army : black men and women remember World War II / Maggi M. Morehouse.

p. cm. (Voices and visions)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8476-9193-4(alk. paper)

1. World War, 19391945Afro-Americans. I. Title. II. Voices and visions (Lanham, Md.)

| D810.N4 M67 2000 |

| 940.54'03dc21 | 00-055257 |

Printed in the United States of America

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Page v

To the special memory of my father, Lee Sinclair Quarterman.Thanks, Dad.

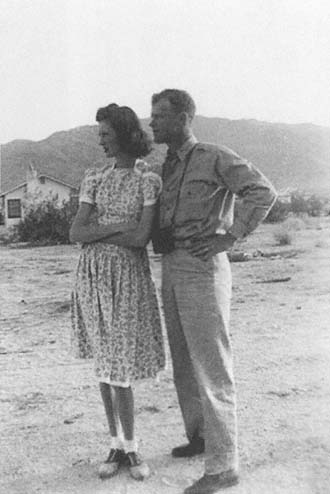

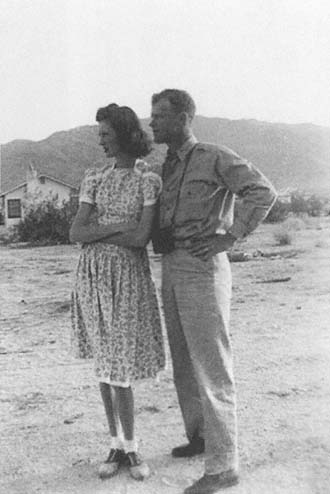

Enjoying the western terrain. Lee and Liz Quarterman in Fort Huachuca, Arizona, in 1942.

Page vi

Page vii

CONTENTS

| Foreword | ix |

|

| Preface | xiii |

|

| Acknowledgments | xvii |

|

| We're in the Army Now | 1 |

|

| Life on the Military Reservation | 41 |

|

| Stateside | 87 |

|

| The Good Fight | 129 |

|

| Coming Home | 185 |

|

| Afterword | 229 |

|

| Methods and Sources | 235 |

|

| Index | 243 |

|

| About the Author | 249 |

Page viii

Page ix

FOREWORD

Postwar America was not simply a historical abstraction when I was growing up in the 1950s and 1960s. Everyone, kids and adults, knew which war we were postit was the Big One, World War II (Korea, somehow, didn't seem to count). Everybody's fathers, it seemed, my own included, had found themselves in uniform at least for some of the years between 1941 and 1945. In fact, all the significant males in our livesour teachers, coaches, Boy Scout leaders, ministers, and the likewere veterans of World War II, as were the presidents we saw nightly on television. Digging out old military gear and apparel from their mothballed existence in the attic and then dressing up in the old man's reflected glory (even if he had never left a training post in the States) was a favorite way to pass a rainy weekend afternoon.

Indeed, the whole culture of the era was saturated with imagery from the war, ranging from the realistic to the fanciful. On our bookshelves at home we had a big red-covered, folio-sized edition of Life's Picture History of World War II , which I pored over endlessly, stirred by the pictures of heavily burdened paratroopers preparing to be dropped over Normandy and grimly fascinated by the pictures of emaciated survivors liberated by Amer-ican forces from concentration camps in Germany. I also read comic books likeSergeant Rock, where the information conveyed was not always as reliable (a regular reader of the genre would come away with the impression that a well-aimed shot from Sergeant Rock's.45 automatic could easily knock an attacking Messerschmidt fighter plane out of commission). My favorite movies were all about the war The Longest Day, The Guns of Navarone , and The Great Escape , among many others. And I regularly

Page x

watched two weekly half-hour television action shows, Combat and The Gallant Men , the one devoted to the experiences of an American army platoon fighting in the hedgerow country of France in 1944, the other to a similar platoon slogging its way up the rocky Italian boot. With such resources at my command, like many other boys, by the age of twelve I considered myself quite the expert on the war.

And by that same age, in my case around 1963, I was absorbing another set of images of a dramatic conflict being waged in freedom's cause: long-suffering black sharecroppers and idealistic black southern college students, standing up at that very moment to bullying white sheriffs and hooded Ku Klux Klansmen in not-so-faraway places such as Birmingham, Alabama, and Greenwood, Mississippi. And although I was from a white family, and lived in a nearly all-white community in rural Connecticut, those nonviolent freedom fighters also became my heroes, just like the veterans of my father's generation.

It would be many years before I made any connections between the two sets of images and two sets of heroes. It simply did not occur to me that black American men had also fought in Europe and the Pacific in the 1940s and that their experiences in the war years had anything to do with the struggles being played out in the churches, courthouses, and streets of the South twenty years later. In retrospect, that is not surprising. There were no blacks in Combat or The Gallant Men . There were no blacks in The Longest Day, The Guns of Navarone , or The Great Escape . There were no blacks in Sergeant Rock . There was one black serviceman represented amid the hundreds of photos reprinted in Life's Picture History of World War II ; he was a U.S. Navy musician in Washington, D.C., in April 1945, weeping as he played Nearer My God to Thee on an accordion in honor of the just-deceased President Franklin D. Roosevelt. It was a powerful image, to be sure, and one that I appreciated much more as the years passed, but not one destined to figure largely in a twelve-year-old's imagination.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.