Note to Reader:In America until the time of the civil rights movement, many white people commonly used language that purposely insulted or demeaned black people. To be historically accurate, I have included quotes from real people verbatim but elected not to spell out offensive words.

Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for and may be obtained from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-1-4197-3160-0

eISBN: 978-1-68335-366-9

Text copyright 2019 Mary Cronk Farrell

Foreword copyright 2019 Marcia M. Anderson

Book design by Erich Lazar

For image credits, see .

Stamp on binding case: Pallas Athenethe Greek goddess of war, wisdom, and virtuewas adopted as the symbol of the WAACs.

Published in 2019 by Abrams Books for Young Readers, an imprint of ABRAMS. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

Abrams Books for Young Readers are available at special discounts when purchased in quantity for premiums and promotions as well as fundraising or educational use. Special editions can also be created to specification. For details, contact specialsales@abramsbooks.com or the address below.

Abrams is a registered trademark of Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

ABRAMS The Art of Books

195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007

abramsbooks.com

To Jeanne and Doris,

my very own army women

Major General Marcia M. Anderson, U.S. Army (Ret.)

Foreword

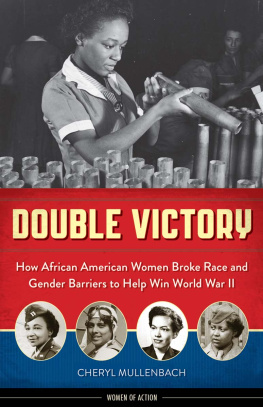

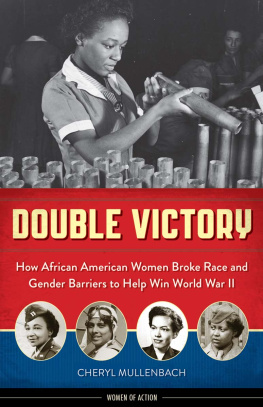

We are more alike than we are different. That is why I am honored to introduce this book about some extraordinary African American women who defied family traditions, culture, and racial norms to join the military during World War II. These are women who, by their lives, words, and actions, prove the senselessness of disliking someone merely because of their gender, race, religion, or ethnicity.

I hope that you will share my pride in the women chronicled in these pages as you learn the story of how they excelled and succeeded in spite of significant barriers to their acceptance and full participation as members of society and the American military.

The hatred that led to the deaths of so many across the globe during World War II was, at its most basic level, the result of people who were afraid of those different than them. They were unable to accept others who did not look, speak, live, or act like themselves and, in doing so, unleashed the powerful forces of fear and ignorance. These forces existed in the United States as well as abroad.

Racism denied African Americans equal treatment in education, employment, medical care, public transportation, and voting. However, denying those basic rights did not deter the persistent strategic efforts of many throughout the African American community. They achieved advanced educational degrees, became successful entrepreneurs, contributed to scientific research, and pursued a steady path forward for the right to full participation in the social and political fabric of the country.

Charity Adams, Alyce Dixon, the Womens Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) officer trainees at Fort Des Moines, the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion, and the thousands of African American women who served during World War II fought daily personal battles and defied long-held racial stereotypes. Their story, powerfully told in the following pages, will resonate with both old and young readers.

The womens struggles began with the high bar for acceptance as members of the WAACs. Their college degrees and professional accomplishments were often not valued by recruiters. And there were low expectations for their ability to adapt to and overcome the rigors of initial military training. They were forced to live and train in segregated facilities that were clearly substandard and unhealthy. And even after successfully completing their training, these courageous women were often not allowed to take the advanced training programs for their specialties, although they were still expected to perform clerical, medical, logistical and other tasks as well as, or even better, than white WAACs.

Their ability to overcome obstacles and exceed expectations is the reason that I, and so many others, have been able to reach the highest levels in the military. Things have changed significantly for African American women since World War II. Over the past ten years alone, we have seen several major generals and lieutenant generals in the Army, Air Force, and Navy, one of whom went on to become an admiral. Two of those women were academy graduates (Naval and West Point). Today, there are several women currently serving in command and senior-level policy positions. And the Marines just nominated a woman to be a brigadier general.

Many of the public and private opportunities that have come my way in recent years are because of my service. The biggest barrier to my success was often personalthe need to remind myself that just because I did not see anyone who looked like me in a job, that did not mean that I could not do it. This is why we must be vigilant and educate ourselves about our history. The lessons we learn from the courage and perseverance of women like Charity Adams and her colleagues convey a powerful message that when we all stand up to hate, everyone wins.

Major General Marcia M. Anderson, Army (Ret.), May 2018

Major General Marcia M. Andersons military career included many firsts, from the time she was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant until she retired in 2016 after thirty-six years of service. In 2010, General Anderson became the first African American Brigadier General to serve as the Deputy Commanding General of the Armys Human Resources Command. She served in that capacity until she was selected as the first African American female Major General in the Army, Army Reserve, or Active Army, and her subsequent assignment as the Deputy Chief, Army Reserve in 2011. She has several military awards, including the Army Distinguished Service Medal as well as the Parachutists Badge.

Major Charity Adams, commander, and Captain Abbie Campbell, executive officer, inspect the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion in England, February 1945.

CHAPTER 1

Reporting for War Duty

Great Britain, 1945

It was a wet, gunmetal-gray February in 1945. Rank upon rank of American khaki-clad soldiers marched down the gangplank of the Ile de France in Glasgow, Scotland. Newsreel cameras rolled and bagpipes played in welcome, and troops were grateful to set foot on dry land. The high, rough waves of the Atlantic had sent many soldiers running to heave their breakfasts and then to their bunks in misery. One night they had been awakened by alarm bells and the ships sudden erratic zigzag course, only discovering later how narrowly they had escaped a German submarine firing torpedoes at their unarmed troop ship.

The United States had galvanized all of its resources in the war against Germany, Italy, and Japan. The fight to stop these totalitarian countries from conquering the world had raged for three years, and who knew when it would end? For the first time, the United States officially allowed women to join the military. They werent sent to battle, but they took over jobs behind the lines to free up men for combat. Thousands of American women signed up to help save democracy and preserve freedom. Yet, in America, blacks did not have the same freedom as whites. In fact, black women, and men, who joined the army were segregated into separate units.

Next page