Table of Contents

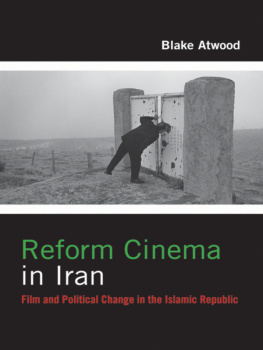

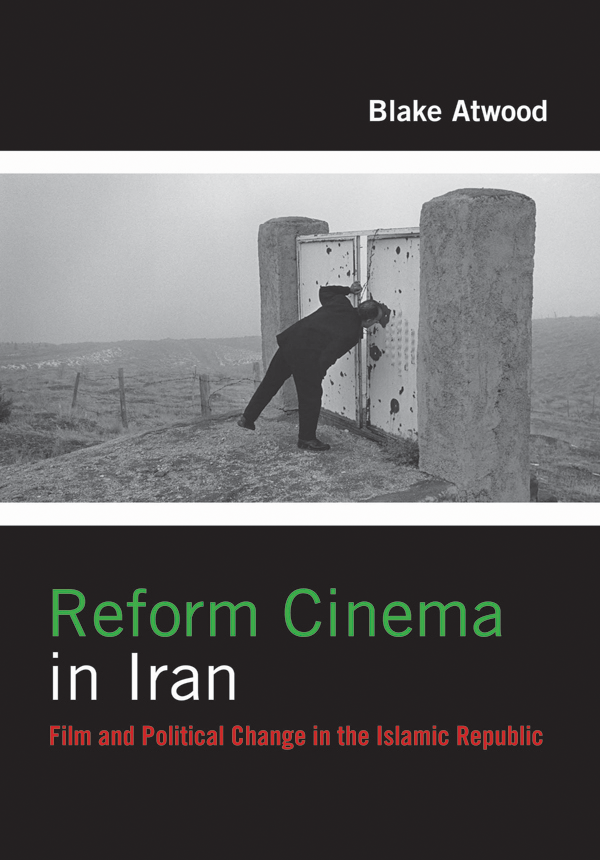

REFORM CINEMA IN IRAN

FILM AND CULTURE SERIES

FILM AND CULTURE

A series of Columbia University Press

Edited by John Belton

See

REFORM CINEMA IN IRAN

Film and Political Change in the Islamic Republic

BLAKE ATWOOD

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

NEW YORK

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2016 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54314-9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Atwood, Blake Robert, 1983- author.

Title: Reform cinema in Iran: film and political change in the Islamic Republic / Blake Atwood.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, 2016. |

Series: Film and culture | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Includes filmography.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016013376 (print) | LCCN 2016019805 (ebook) | ISBN 9780231178167 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780231178174 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780231543149 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Motion picturesIranHistory20th century. | Motion picturesIranHistory21st century. | Motion picturesPolitical aspectsIran. | Motion picture industryPolitical aspectsIran20th century.

Classification: LCC PN1993.5.I846 A89 2016 (print) | LCC PN1993.5.I846 (ebook) | DDC 791.430955dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016013376

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover image: Film director Abbas Kiarostami. A. Abbas/Magnum Photos. IRAN. Tehran. 1997.

CONTENTS

For the transliteration of Persian words, I have followed the Iranian Studies transliteration scheme. Diacritical marks have been excluded on all proper nouns. I have done my best to ascertain the preferred or standardized spelling of Iranian names (e.g., Khomeini, Ahmadinejad, and Khamenei). In those cases in which I could not determine a preferred spelling, I have transliterated the name according to the Iranian Studies scheme but have not included any diacritical marks.

So much of my intellectual work over the last decade has taken place in the Department of Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, and I cannot begin to thank all of the wonderful people with whom I have interacted at UT, first, as a student and, later, as a faculty member: Kamran Aghaie, Mahmoud Al-Batal, Samer Ali, Katie Aslan, Denise Beachum, Kristen Brustad, Mia Carter, Tarek El-Ariss, Michael Hillmann, David Justh, Briana Medearis, Naama Pat-el, and Faegheh Shirazi. Several people at UT deserve special thanks. M. R. Ghanoonparvar has tirelessly encouraged my work since I first showed up in his office as a first-year graduate student, and I could not have asked for a better adviser. Tom Garza has shown me unbounded kindness, and our lunches once a month make my life much better. Karen Grumberg is a good friend and encouraging colleague, and I feel very lucky to have an office next to hers. Karin Wilkinss guidance has made navigating the academic waters at UT much easier, and I am very grateful for her friendship. I have also had the good fortunate of working with several exceptional graduate students at UT: Shahrzad Ahmadi, Claire Cooley, and Laura Fish, whose enthusiasm, research, and comments have pushed my ideas further and enriched my own work. I would also like to acknowledge a University of Texas at Austin Subvention Grant awarded by the Office of the President, which supported the publication of this book.

I am very lucky to have a network of professional support that extends well beyond the Forty Acres, and colleagues around the world have contributed to this book in innumerable ways: Zeina Halabi, Nili Gold, Mikiya Koyagi, Neda Maghbouleh, Drew Paul, Kelsey Rice, Lior Sternfeld, and Richard Zettler. I am particularly grateful to Nasrin Rahimieh, whose work and kindness inspire me, and Peter Decherney, who has been a great collaborator, friend, and mentor to me over the last five years. Farzaneh Milani and Zjaleh Hajibashi nurtured my early passion for Persian at the University of Virginia, and I cannot begin to thank them enough. At Columbia University Press, Id like to thank John Belton and Philip Leventhal for believing in this book and my work. Jinping Wang has been the greatest friend and intellectual interlocutor that any academic could hope for; our many conversations about history and the world have marked every page of this book in some way.

Many good friends have given me the space to work on this book but have also reminded me that there is life outside of it. Dena Afrasiabi, Beeta Baghoolizadeh, Raha Rafii, Sahba Shayani, and, Anousha Shahsavari have all been pillars of support when I needed them most, and all of them have reminded me in their own way of the importance of friendship. Anthony Ferraro is the kindest person I know, and without his friendship, this book would not have been possible. Erin Micheletti, my oldest friend, read every page of this manuscript, and I am so appreciative not only for her critical eye but also for our adventures in Austin. Sadafs enthusiasm for this project, Khatami, Tehran, and Persian inspired me to keep writing, and her help with sources made all the difference. Vrouyr Joubanian is my favorite person in the world, and there are no words in any language to express my gratitude for everything he does for me.

I am eternally grateful to my family, who has contributed to this book and to all my pursuits in so many ways. My father always prioritized education, and I attribute my career as an educator to him. My siblings, Seth, Jessica, Ashley, and Tyler, love me unconditionally, which makes me feel like I can do anything in the world. And, finally, I owe so much to my mother, who has always encouraged me to be myself and who came all the way to Iran with me to understand what I do. Her bravery and open-mindedness never cease to surprise and inspire me. Thank you.

Film, since its inception, has danced in the shadows of wild political change. With early examples like the conflict implicit in Soviet montage theory of the 1920s and Benito Mussolinis Cinecitt Film Studio (est. 1937), whose motto was Film Is the Most Powerful Weapon, the history of world cinema is also a history of violence. Third Cinema, an aesthetic movement that emerged alongside the Latin American liberation struggles of the 1960s and 1970s, redirected this history of violence to the service of anti-imperialism, in which film was no longer just an apparatus for propaganda but also an agent of resistance and opposition. The political implications of such a project were vast, and the possibility of resistance through filmmaking fueled, and still propels, the efforts of filmmakers around the world, especially in non-Western cinemas. The Syrian Abounaddara Collective, for example, reminds us of the continuing relevance of cinema to the violent struggles that seek political change. The collectives ongoing emergency cinema has sought to provide an alternative to the Assad regimes narrative by releasing one short video of the conflict each week since the civil war began in 2011. At a time of unprecedented access to visual information, as guns and cameras seem to battle for authority around the world, it is important to remember that for more than a century cinema has been ideologically and technologically entangled with the idea of revolution.