Table of Contents

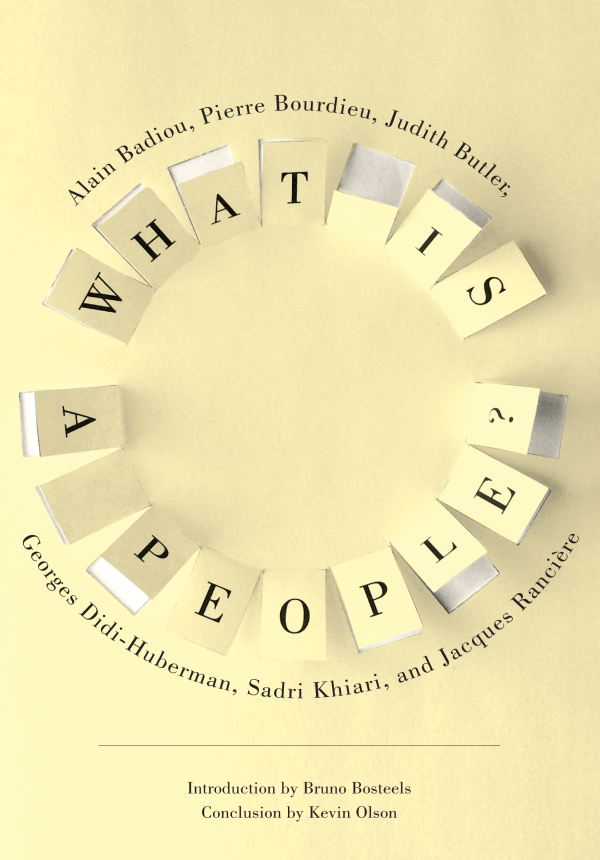

WHAT IS A PEOPLE?

NEW DIRECTIONS IN CRITICAL THEORY

NEW DIRECTIONS IN CRITICAL THEORY

Amy Allen, General Editor

New Directions in Critical Theory presents outstanding classic and contemporary texts in the tradition of critical social theory, broadly construed. The series aims to renew and advance the program of critical social theory, with a particular focus on theorizing contemporary struggles around gender, race, sexuality, class, and globalization and their complex interconnections.

For a complete list of the series see

WHAT IS A PEOPLE?

Alain Badiou, Pierre Bourdieu, Judith Butler, Georges Didi-Huberman, Sadri Khiari, and Jacques Rancire

Introduction by Bruno Bosteels and Conclusion by Kevin Olson

Translated by Jody Gladding

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Quest-ce quun peuple? 2013 La Fabrique-ditions

English translation 2016 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54171-8

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Badiou, Alain, author.

Title: What is a people? / Alain Badiou, Pierre Bourdieu,

Judith Butler, Georges Didi-Huberman, Sadri Khiari, and Jacques Rancire ;

introduction by Bruno Bosteels and Conclusion by Kevin Olson ;

translated by Jody Gladding.

Other titles: Quest-ce quun peuple? English

Description: New York : Columbia University Press,

2016. | Series: New directions in critical theory |

Translation of: Quest-ce quun peuple? |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015042650 | ISBN 9780231168762

(cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780231541718 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Democracy. | Populism. | Group identity. | People

(Constitutional law) | Political sciencePhilosophy. | Social

classesPolitical aspects. | Nation-state.

Classification: LCC JC423 .Q46513 2016 | DDC 320.56/62dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015042650

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: David Drummond

References to websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

CONTENTS

BRUNO BOSTEELS

ALAIN BADIOU

PIERRE BOURDIEU

JUDITH BUTLER

GEORGES DIDI-HUBERMAN

SADRI KHIARI

JACQUES RANCIRE

KEVIN OLSON

The child is the interpreter of the people. What am I saying? He is the people itself, in its native truth, before it is deformed, the people without vulgarity, without rudeness, without envy, inspiring neither defiance nor repulsion. Michelets words can make us smile, but when we speak of popular (language) or of populist (discourse), isnt there a kind of defiance and repulsion there?

The plan for this book grew out of our anxiety at seeing the word people hopelessly joined with the group of words like republic or secularism, whose meanings have evolved to serve to maintain the order. Despite their diversity, what the texts brought together here have in common is demonstrating that people remains solidly rooted on the side of emancipation.

BRUNO BOSTEELS

To raise the question What is a people? always means at the same time to make some statement, even if only implicitly, about who or what is not a people. The six interventions collected in this slender volume are no exception in this regard: while they all to a greater or lesser extent plead in favor of the people as a political category that is still valid today, they also at the same time draw a negative profilelike a chalk outline at the scene of a crimeof whoever does not constitute a people.

This negative delimitation in turn can be said to take two fundamental forms. On one hand, the category of the people is always overtly or covertly opposed to a series of other categories in political thought that by the same token we are invited to discard, criticize, or overcome. Among such alternative options, we could mention not only nation, state, or civil society but also races, masses, and classes, as well as a whole slew of other terms more typically associated with the disciplines of anthropology, sociology, and so-called group or mass psychology, such as horde, tribe, clan, pack, crowd, commune, or community. To be sure, many of these concepts can and do enter into systematic combinations and historical articulations, most notably around the racialized triad of people, nation, and state so central in the constitution of the modern world-system. But even in such cases where the term becomes part of a larger configuration, any strategic privilege given to the concept of the people immediately causes a chain reaction in the political evaluation of its alternatives. Already the use of the indefinite article in the question What is a people? invites us to abandon the essentialist presuppositions behind the people and opens up the possibility of talking about peoples in the plural. This may be linguistically awkward in English but in other languages, such as Spanish, helps draw critical attention to the indigenous presence that continues to resist the colonial framing of the capitalist world-system dominated by the Westwith los pueblos originarios, for example, constituting key political actors throughout much of Latin America today. On the other hand, no sooner is the term chosen than the people also begins to function as an exclusionary category in its own right, always in need of being internally demarcated from that which is not yet or no longer part thereof and which for this same reason tends to be relegated more or less violently to the pre-political or nonpolitical realm indicated by the pejorative use of terms such as plebs, populace, mob, or rabble.

Whichever way we designate those who are either not the people or other than the people, there is no way of circumnavigating the fact that, both historically and conceptually speaking, this category is constituted on the basis of a necessary exclusion. Specifically, the political logic of the people can be said to operate according to the principle of a constitutive outside in at least a double sense: by choosing the people, or a people, as a privileged term for articulating the sphere of modern politics, contemporary thought inevitably marginalizes or bans from the discussion a number of other terms, while raising the even more troubling issue of how to name and take stock of whoever falls outside of the political realm so designated and often as a result no longer even appears as a who deserving of calling itself a subject but ends up being targeted as a mere object of denigration and exploitation. The fundamental decision to be made in this context, however, is whether or not we take this logic of exclusion to be capable of erecting insurmountable obstacles on the path to the continued use of the people as a political category today.

For example, not everyone in todays world of war-and-oil-driven globalization will so readily identify with the seemingly egalitarian and emancipatory invocation of We, the people, taken up here by Judith Butler as the starting point for a wide-ranging reflection on the self-constitution of political subjects, with a special eye on the new era of protests and uprisings announced in the movements in Tahrir Square in Egypt or Puerta del Sol in Spain. To the contrary, as the opening words of the preamble to the constitution of one country in particular, this expressionat least in Englishwill strike many as being all too deeply ensnared in the history of the United States of America, from the early days of its independence to its unbridled economic expansionism and military interventionism today. However, does this mean that the subjective self-assertion of any people whatsoever, as the embodiment of a plural we emancipating itself from the instituted powers that be, should cease to be prescriptive in general? And should the role of political theory thenceforth be limited to the extreme vigilance with which one points out, stands guard over, and endlessly deconstructs the inevitable hierarchies and exceptions without which no people has ever been capable of constituting itself? Or else, without unduly generalizing one nations particular history as our universal model, whether that of the United States or France, can the category of the people be salvaged from the combined wreckage of national chauvinism and imperialist expansionism so as to be rescued for genuinely emancipatory purposes? And, in that case, whether it takes place in philosophy or sociology, in political science or the study of language and art, can the work of theory actually contribute to the sharpening of this political potential, rather than shielding itself in the irrefutable radicalism reserved for those rare ones whostanding on the sidelines or tracking down one crisis after the other as so many ambulance chasersare uniquely capable of seeing through all the blind spots of contemporary politics, whether on the left or on the right?